Unpacking Idiosyncratic Things and Mental Illness

In the wake of World War II, Ukranian farmer Dmytro met his eventual wife Sophia in a displaced persons camp, and the couple migrated to the US in 1949. The former Nazi prisoner and his wife made their way to Syracuse, where Sophia died during a miscarriage in 1951. In the wake of her death Dmytro declined and was hospitalized at Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane.

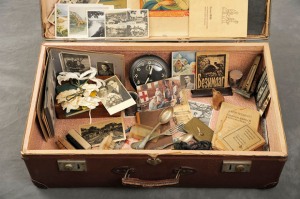

Dmytro arrived at Willard in May, 1953 with a plain brown leather suitcase laden with personal photographs, a Washington Monument thermometer, a carved dog knick knack, immigration paperwork, flowers (from his wedding, for which he had a photograph), notebooks laden with complicated mathematical work, and a clock amidst some personal effects. The things were idiosyncratic but consequential invocations of Dmytro’s life, prosaic things he or his friends may have hoped would anchor him in the face of mental illness. Dmytre (as he came to be known in Willard) remained in the hospital until 1977, spending much of his time painting and eventually moving to some smaller homes before his death in 2000.

Frank’s Army uniform was among the rich assemblage of things he brought to Willard (image Jon Crispin).

Dmytro’s suitcase remained behind at Willard, along with over 400 other suitcases of patients who arrived at the hospital in similarly bleak life moments clasping simply a few things. On the one hand, the suitcases are not especially unlike any archaeological things: long separated from the people who once held them, the suitcases hold assemblages of things around which we now weave narratives about the people who once carried them into Willard. On the other hand, though, words seem to clumsily capture the desperation and disconnection of Willard patients like Dmytro. Jon Crispin’s continuing photo project documenting the suitcases focuses on the visual and material dimensions of the suitcases in an effort to tell the patients’ stories with aesthetically compelling yet prosaic things. The sober measured steps of conventional archaeological storytelling might be expanded by confronting the intersection of materiality, aesthetics, and our own emotional reactions to these things.

Thelma’s suitcase included religious literature, knick knacks, and a Tony Martin record (image Jon Crispin).

The standard archaeological assumption is that things simply reflect various dimensions of identity like wealth or ethnicity; archaeologists acknowledge measures of irrationality, idiosyncrasy, or imagination are part of all materiality, but since we cannot systematically account for and explain them we generally place them outside archaeological narrative. The Willard suitcases may reflect some contextually distinctive material symbolism in the hands of patients, and perhaps the Willard patients had a material imagination that reaches beyond stereotypical rationality. Nevertheless, that does not imply that everyday consumption outside Willard’s walls is rational, conscious, and strategic, and the asylum suitcases probably make no more or less sense than any bourgeois living room.

In a moment of unique desperation at the boundaries of self-conscious reflection and mental illness, the suitcases might have been packed with a vast range of intentions by patients and families alike. Dmytro, for instance, appears to have held tightly to his past, as did many of his fellow patients. Irma had traveled throughout Europe (including a 1925 French trip documented in the notebooks in her Willard suitcase) and taught languages in New York City before being admitted to Willard in the late 1930s. Like Dmytro her suitcase was laden with the evidence of a rich life before Willard, including a dense range of sheet music and travel literature. Irma would never leave Willard, dying there in 1971. Frank was admitted after World War II, and his suitcase included a dense collection of wartime paperwork documenting his service as well as his uniform and personal photographs (alongside objects like pliers and luggage tags). Frank was only at Willard for three years, but he went from there to a Veteran’s Administration facility and never lived outside institutions before his death in 1984. Anna died in Willard in 1987, leaving a suitcase with a carefully transcribed list of her stylish clothing, some of which remained in the suitcase. Thelma’s fascinating suitcase included a collection of religious literature, dog figurines, the Tony Martin record “I Guess I’ll Have to Dream the Rest,” the circa 1948 pamphlet “A Primer on Race” by the Northern Baptist Convention Council on Christian Social Progress, and a figurine of a couple.

Josephine was admitted in 1898 with a ceramic plate and personal photographs in her assemblage (image Jon Crispin).

After Willard closed in 1995 the suitcases were displayed in the exhibit “Lost Cases, Recovered Lives: Suitcases from a State Hospital Attic,” which became the online exhibit The Lives they Left Behind. Jon Crispin began to systematically photograph the Willard suitcase contents in 2011, capturing their evocative aesthetics and our own imagination of life in an asylum. There is perhaps a tendency to interpret the suitcases as expressions of some consistent logic, but they are not simply systematic biographical narratives. In Crispin’s hands the suitcase owners have biographies, but they and their long-lost intentions are perhaps less significant than our own imaginations. We may cast the suitcases as vehicles for storytelling, the material evidence of otherwise lost lives; however, we might just as well accept them as the emotionally fascinating things they are, leading us to a compelling if inchoate imagination about the boundaries of madness and normality and their intersection with prosaic materiality.

Like many if not most archaeological assemblages, our interpretations of the suitcases are shaped by the contents themselves as visual and material things. The suitcases are not really about intentions; that is, they are not simply documents of how a patient or their families intended to shape the experience of life in a total institution. Instead, they are fascinating because they evoke the barely expressible but visually and materially arresting boundaries of human experience.

The Willard attic where the suitcases remained preserved in storage after closing in 1995 (image Jon Crispin)

References

Yaro Bihun

2004 Life of “Dmytre Z.” emerges thanks to exhibit, and some journalistic sleuthing. Ukrainian Weekly 14 Mar 2004: 1.

Fiona R. Parrott

2005 “It’s Not Forever: The Material Culture of Hope. Journal of Material Culture 10(3):245-262. (subscription access)

Images

Dmytre Suitcase image, Frank suitcase image, Thelma suitcase image, Thelma figurine image, Robert’s suitcase image, Josephine suitcase image from Jon Crispin

Posted on March 3, 2014, in Uncategorized and tagged Jon Crispin, Suitcase Project, Willard Asylum. Bookmark the permalink. 9 Comments.

It seems the danger is that of projecting insanity and our assumptions onto these beautiful things. I thought about my own collections of things from moments of my life. I learned the year I was in China that the most important things for me to bring home were the things I used every day — the scale I carried to the market to make sure I wasn’t being ripped off by the peasant farmers, notebooks from the store in the village. I didn’t want to leave China so my return to the US was a kind of exile of the heart — much like these poor souls in that way. Lovely piece. I enjoy reading these so much.

Perhaps it is less about determining specifically what things mean to us or these folks who came to end up in Willard; instead, I think it is more interesting to assess what they might have meant to particular people in these sorts of circumstances and what they really do make us feel about mental illness and this unpleasant 20th-century institutional experience. Thanks as always for the thoughts.

Reblogged this on elections in india.

Interesting. People are so much more than any one thing, but this is a lovely story of assumptions and stories, who people were and the different narratives around that (and those possibly missing too). I have to wonder though, whether the people in the asylum would be there in modern day circumstances, with a deeper understanding that sometimes we define madness according to setting? Such a lovely article!

I love this article and I can’t wait to read more from you! 🙂

Reblogged this on sordidday.

Reblogged this on Dumadia's Blog.

Pingback: Unpacking Idiosyncratic Things and Mental Illness | Human Relationships

Pingback: Miscellaneous Stuff | Jon Crispin's Notebook