Monthly Archives: March 2013

The Beautiful Past: Televising History

Popular culture has been graced by Vikings, cowboys, Roman legions, and gangsters for well over a century, but the historical serial has apparently found a fresh audience on cable television. The newly popular historical drama features captivating historical narratives, dramatic past personalities, lyrical dialogue and plots, and beautiful scenery personified by the likes of Rome, The Tudors, Deadwood, The Borgias, Spartacus, Boardwalk Empire, and, most recently, Vikings. This new wave of programs weaves a fascinating, if unsettling story about society past and present: In the midst of seemingly timeless moral and ethical quandaries, society seems persistently materialistic, violent, and carnal, but paradoxically beautiful and compelling.

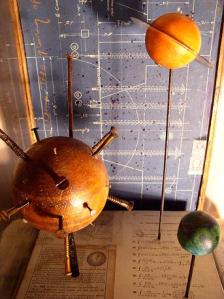

The most recent entry into the surprisingly cluttered historical series landscape is Vikings. The first filming of the Norsemen’s story was apparently 1928’s The Viking, a full-color silent movie replete with pillaging, the beautiful love interest Pauline Starke, and Leif Ericson’s conversion to Christianity. Kirk Douglas’ 1958 The Vikings told the story of Ragnar Lodbrok’s murder of the King of Northumbria during a raid, leaving his widow pregnant with Ragnar’s son, who is eventually spirited away by the Vikings only to be pitted against his half-brother.

In comparison to its peers on pay-cable, Vikings’ carnality is distinctly more implied than depicted.

Portrayed by Ernest Borgnine in 1958, the role of Ragnar is now former Calvin Klein underwear model Travis Fimmel. This new Ragnar was one of People magazine’s sexiest bachelors of 2002 and began his acting career playing Tarzan in 2003. Vikings shares with most of these shows a fascination with such a stylish past punctuated by fabulous wardrobes, alluring settings, costly graphics, and beautiful people prone to persistent nudity. At some level the genre’s visual beauty invested in sumptuous wardrobes, picturesque settings, and the casts’ bodies is a distraction from the historical details of events that unfolded in vastly more prosaic forms and without the resolute dynamics painted in most of the plot lines. Historical narratives have always been a staple of popular fiction, the silver screen, and television, routinely reminding society of timeless human attributes and challenges while obliquely and sometimes clumsily commenting on contemporary social life. The genre features many real historical figures, and like the overdone material landscape of the genre most of the familiar historical personages are painted as morally polarized characters who are self–interested (Deadwood’s Al Swearengen), hyper-violent (Spartacus’ gore is cartoonish), nearly always gorgeous (The Tudors’ Jonathan Rhys Meyers fails to scratch the surface of Henry VIII’s obesity), and eagerly carnal (Rome). These characters are hyperbolized versions of ourselves projected onto the already-monumental likes of Julius Caesar, the rebel leader Spartacus, and Henry VIII, oddly appealing for their mastery of the dark and extreme dimensions of human nature.

We know relatively little about some of these figures, and much of the dramatic detail of their lives and societies are submerged in dense historical documents or simply inaccessible altogether. The shows toe an ambiguous line between historical narrative and liberal reinterpretation projecting scholarship onto a breadth of popular media, with the History Channel acknowledging that the Viking age is “a topic that has always resonated with our viewers through our historical documentaries. Hopefully it’s very appealing to a core young male audience — I think there are some parallels to some of the video games that are being played today by young men.” Indeed, the basic formula for Vikings is not all that different from Game of Thrones: Game of Thrones is a fantasy historical serial that shares the splashy visuals, captivating plot lines, and brutality and sexuality that appear to have characterized the Roman world, the American West, and English courts over two millennia.

The rebels from Spartacus charge the Romans in what may be the most gory of all the historical series.

That complicated interchange between popular culture and scholarship has long made many scholars wary of such shows, and the marriage between historical accuracy and dramatic effect is inevitably complicated. Deadwood creator David Milch noted in 2005 that “I’ve had my ass bored off by many things that are historically accurate. … this is not a piece of nonfiction.” The genre does indeed distort real historical facts for shows’ own dramatic interests and ideologically distorted purposes, but Monty Dobson made the case for Vikings that “I get that it’s fiction. It is not a conference paper or journal article and let’s face it, if it were no one would watch. … Dramatizations like Vikings can spark people’s curiosity and move them to learn more about the subject. We just have to be willing to embrace their curiosity. As archaeologists and historians, we have the best stories in the history of humanity at our fingertips, and yet we are too often unwilling to share them, and can be terrible storytellers.”

Sometimes such representations are charged with deeper ideological distortions. In 1960, for instance, a group of classical scholars protested the film Spartacus, arguing that “the manufacturers have crammed enough sadism, violence, bloodshed, and sex to keep their adolescent audiences tittering happily. … The political bias underlying left-wing author Howard Fast’s Spartacus–a shallow, rather silly and thoroughly uninformed piece of parlor pink propaganda–has been faithfully reproduced in left-winger Dalton Trumbo’s screenplay. Spartacus, the perennial hero of international Communism, leads the exploited proletariat in which all virtues are vested, while a jaded, decadent, and `fascist’ bourgeoisie is riddled with all the vices.” Lars Walker sounded a similar note on the unacknowledged politics of historical programming when he criticized Vikings’ portrayal of autocratic Viking rule in a society Walker argues was quite democratic. Walker argued that “this is not in any way an accurate depiction of the political system of the Vikings. Rather, it’s an expression of the tropes to which lazy contemporary scriptwriters are prone. Every story has to be about some dynamic young person (who wants freedom) in conflict with a hidebound old conservative, who lives by oppression.” This may not be quite the profound ideological contest Walker divines, but he is correct that there is something emotionally satisfying albeit contrived about the tension between the young “Viking warrior and farmer who yearns to explore—and raid—the distant shores across the ocean” and the authoritarian “local chieftain … who insists on sending his raiders to the impoverished east rather than the uncharted west.”

All of these shows have some consultant historian(s), but the referents for the genre are often ambiguous and scattered historical facts projected onto earlier popular cultural referents and the random creative instincts of producers, writers, and designers on the shows. The Vikings’ costume designer, for example, conducted preliminary research “mainly at Scandinavian museums, which are exemplary in the way they show all the great findings, and although a lot of the fabrics have rotted, there are a lot of artifacts and jewelry. … I built up a very general picture of how they looked, but I discovered that perhaps there wasn’t enough there to sustain visual interest for nine episodes. I had to take a leap of faith. Overall, I think you just try to be as true and as original as you can and take some liberties to make it interesting.” Entertainment Weekly concluded that “Male or female, the clothes say a lot about the Viking,” with the costume designer noting that “`If you were a Viking, you murdered people who were your enemies for the greater good of something else. Paganism … is a culture, it’s a different way of looking at the world, and I think that even in a little way I managed to convey that through the clothes. That would be my slogan for the T-shirt: These people were different.’”

Actually the slogan might instead be that these people are the same as us: the Romans, Tudors, Vikings, and cowboys populating historical serials are compelling but predictable personalities that ultimately distill much of our own society into its most caricatured representations. The act of interpreting these experiences and characters—literally making movies and television series, or writing historical novels consciously framed as distinct from us–may be what actually makes them seem alien; we ultimately see ourselves in these narratives even as we are distanced from the unsettling violence and mutable moralities such shows paint.

The Tudors suggests that we were grossly misinformed about the attractiveness of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn.

The lush beauty of these shows and their skill compressing complex events into rapidly paced narratives allows us to experience their fundamental brutality, selfishness, and violence as entertainment detached from our society. As accurate history they are of course not especially useful mechanisms; the mining of visual mechanisms and rhetorical plots from earlier films, shows, and novels imitates that which was a shallow construction in the first place; and the moral and political messages of these shows are often rather shallow. Yet as compelling stories they are still consequential as confirmation of pasts that persistently tug on contemporary imagination.

References (both subscription access only)

John Mack Faragher

2007 HBO’s “Deadwood”: Not Your Typical Western. Montana: The Magazine of Western History 57(3):60-65, 96

Harry C. Schnur, Harry L. Levy, Paul MacKendrick, Agnes K. L. Michels, James A. Notopoulos and William H. Stahl

1960 In the Entertainment World: Spartacus. The Classical World 54(3):103-104.

Toy Narratives: Childhood and Global Consumption

The Italian photographer Gabriele Galimberti is an anthropologist of sorts, capturing and comparing individual people in relatively universal moments—Coffee Surfing: In Search of Sips of Happiness features people drinking a cup of coffee; Delicatessen with Love tells the story of grandmothers and their favorite dishes; and CouchSurfing documents a year Galimberti spent on strangers’ couches throughout the world. The projects are visual narratives that compare people across all social stations and lines of geographical and cultural difference, invoking common humanity around mostly universal acts like eating, sleeping, and parenting.

His series Toy Stories cleverly weaves material things into this narrative and visual mechanics. Galimberti took pictures of children with their favorite toys, straightforward images of children with a few toys in their own spaces. Most of the toys are quite familiar, and the rooms might be in nearly any place, so the project paints a picture of considerable commonalities. The narrative in this and many of Galimberti’s other projects tends to revolve around leveling distinctions and difference: plastic dinosaurs, for instance, patrol the distant reaches of Malta, Malawi, and Texas; Barbie reigns over bedrooms in Haiti, the Philippines, and Albania; Lego is found in Alaska and South Africa alike; and fabulous cars are part of the landscape in Iceland, Latvia, and Thailand.

It is difficult to instantly look at any of Galimberti’s images and know the child’s class standing or where they live, and of course that is one of the project’s most interesting implications: all of the dimensions of identity that we take for granted as being marked by our things and our bodies are not especially clear if plausible when we ponder an image of a kid and their toys. Some places are distinctive—the sun-bathed path of Maudy’s home in Zambia, or the well-appointed bedroom of Tyra in Sweden—but they are difficult to reduce to facile class and nationalist caricatures. The goods that fill these global toy boxes are not surprisingly highly standardized, so the project does not ignore that children—and the parents buying their toys–are increasingly socialized in a universal marketplace. Some toy assemblages and spaces in the project seem stylish, fresh, and perhaps even costly, while others have the patina of extensive play and inhabit spare spaces. Yet Galimberti argues that in general the images reflect that children are universally much the same and simply “want to play.”

The intimacy of Galimberti’s images, the hint of children’s proud innocent possession, and the implication that such modest toys are more than mere commodities in the hands of a child makes for a compelling visual study of material things. The project ends up being a measured yet complicated critique of global consumption. On the one hand, the multitude of Barbie’s and the Barbie-pink bedroom of Julia in Albania underscores the utterly total reach of the marketplace into every child and parent’s life. On the other hand, though, it is hard to reduce these children simply to automatons, because the images give them grace, happiness, and naivety that seems truly universal and seems unlikely to be vanquished simply by mass-produced plastics. The project delivers a thoughtful anthropological moment of self-reflection by making us contemplate how we see ourselves and others mirrored in such otherwise mundane things.

Detritus as Muse: Trash and the Failure of the New

Kipp Normand refers to himself as a “junk artist,” one of many “found object” artists who re-purpose the prosaic and discarded things littering the landscape. Normand follows in a rich line of late-20th and early 21st-century artists who have delivered the death rites to “high art,” with many celebrating the aesthetics of trash itself.

In one sense, this transgressive move complicates what constitutes detritus and art alike, forcing us to contemplate aesthetic conventions. At another more interesting level, though, Normand’s creations capture a broadly based social practice of recycling, fetishizing, scavenging, rehabilitating, and repurposing commonplace things. The Indianapolis-based Normand acknowledges that “refuse is my muse,” providing a telling read on stylistic innovation and material narratives. For an aesthete, the artwork itself is the point of departure, but the process by which Normand and his peers make art—that is, the assembling of scattered discards that have become vacuums of meaning—is perhaps more interesting than the actual creations themselves.

On the one hand, this fabrication of meaning from discarded things that have been purged of consequential meaning is perhaps typical of contemporary consumption. Nearly 30 years ago, Frederic Jameson imagined a world of “nothing but stylistic diversity and heterogeneity.” Jameson prophesied a world in which there was no “normality” against which all styles could be judged; that is, stylistic innovation is no longer possible: all that is left is to imitate dead styles. In this assessment, normative codes had been replaced by myriad private if not individual styles. Jameson’s picture may be borne out by the consumption of discards: that is, thrift shops, mass-produced retro, flea markets, online markets, and trash artists have complicated what is a discard.

On the other hand, this artistic production begs the thorny question of precisely what defines trash and what sorts of meanings we seem compelled to project onto it. Trash invokes the meaninglessness of rot and decay, which theoretically happens to all things and has often been construed as a sort of death. Trash tends to retain its power and cling to meaningfulness when it is symbolically visible or materially dangerous; for instance, hazardous materials, aesthetically unpleasant litter, un-recycled plastic bottles, foul smelling discards, and abandoned buildings retain some agency that is lost by the eroded thing that returns to the earth.

Found things are often classed as “trash” simply as a rhetorical maneuver compelling us to define waste and aesthetics. Trash artists have a broad range of concrete political interests reaching beyond the question of what defines art, including environmental consciousness, hoarding, biodegradation, and recycling; however, they tend to share a broad common interest in giving meaning to detritus and preventing it from becoming invisible or unseen. Indeed, this is precisely what archaeology does: we excavate discards and invest them with new historicized meanings that at least implicitly illuminate who we are or how we see contemporary society.

Gillian Whiteley’s study Junk: Art and the Politics of Trash calls the artists who construct meaning from discards “bricoleurs.” The bricoleur assembles meaning from fragments, as when Kipp Normand makes “sculpture and collage images out of things I find around our city. I spend a lot of time by myself making things out of broken and discarded objects.” While artists had worked with found objects since the early 20th century, such works became a recognizable oeuvre after the 1961 Museum of Modern Art exhibit “Art of the Assemblage.” Often referred to as assemblage artists or upcyclers, such three-dimensional collage incorporating found objects and discarded things is commonplace and reaches from the toniest art galleries to the pages of Etsy. A 2011 Sotheby’s auction of assembled art pretentiously referred to such works as the products of “hunting and gathering” that reflect a primal urge to collect and define the mysterious, meaningless, or misplaced.

One effect of this improvisational consumption style is that we could perhaps fancy that we are all “bricoleurs” fabricating the world to our own stylistic whimsy. Indeed, his studio’s web page is simply one of the sites that emphasize that “Normand has no formal training in art.” This rhetorical maneuver obliquely situates Normand’s vision in experience, which we all possess and articulate in our living room decorations, refrigerator art displays, and everyday fashion. Normand’s mission finding “stories in discarded things” may not be fundamentally different from retro shoppers who are likewise cannibalizing styles and investing them with new meanings. The dilemma is that this apparently democratic embrace of creativity risks repudiating critical analysis of style, aesthetics, and art because experience seems beyond intellectual challenge.

Jameson suggested that we were entering a moment in which we perpetually seek a historical past, which is reflected in the mining of dead styles. Jameson suggested that art in this context was about “the failure of the new,” an inability to imagine ourselves in new ways that step beyond historicized styles. The postmodern lament that there is “nothing new” is perhaps overdramatized, but contemporary style certainly is pervaded by romanticized nostalgic representations.

Plastic bag art in The Center for Environmental Education of the Dan Region Association of Towns, Tel-Aviv (image courtesy sielju).

Normand himself quite consciously focuses his trash compositions on a heritage that is materialized in discards characterized by patina, lost functions, and the absence of “new-ness.” This artistic trend is certainly mirrored in broader consumer culture styles including old school gaming, vintage bowling shirts, pin-up dress, retrofuturism, throwback uniforms, Eddie Rockets retro diners, and a store named after Bettie Page hawking retro dog collars. Normand’s ambition to project historicized, locally distinctive meanings onto salvaged things is at odds with this nearly meaningless “retro” style that loosely evokes a past that comes from popular culture rather than critical historical consciousness. When a local television commentator referred to Normand as a “hipster artist,” it risked reducing the bricolage aspect of Normand’s work simply to a shopping style.

Kipp Normand apparently hopes to evoke the fabric and lost lives of a historical city with its detritus—indeed, a very archaeological sentiment. Like such assemblage artists working with trash, many archaeologists aspire to provide a critical insight into social and historical realities that may be activist, subversive, and oppositional. This runs directly against the tendency to transform such realities into pleasant and consumable styles purged of historical substance and reduced to hollow aesthetics. Heritage in this moment risks becoming a commodity, but trash—the most material vestiges of our march across time—may provide a particularly powerful mechanism to rethink art and heritage alike.

Discard Studies has an inventory of artists who work primarily with trash; compare Integral Drift’s blog posting Regarding Trash; the blog Rubbish; Everyday Trash‘s inventory of “artistic trash”; Scott Hocking‘s web page; the trailer for the movie Waste Land; and Schwitters in Britain

For more on Kipp Normand, visit the Harrison Center flickr sets for the show TRASH, Kipp’s Studio, and Kipp Normand. Also see the trailer for Jonathan Frey’s short film Kipp Normand, the WISH-TV profile, Dressing Indianapolis, and his Indy Arts profile.

References

Roland Barthes

2001 The Death of the Author. In The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, ed. Vincent B. Leitch, et al. pp.1466-1475. Norton, New York.

Stephanie Foote and Elizabeth Mazzolini

2012 Histories of the Dustheap: Waste, Material Cultures. Social Justice MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Frederic Jameson

1985 Postmodernism and Consumer Society. In Postmodern Culture, Hal Foster ed., pp.13-29. Pluto Press.

1998 The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983-1998. Verso, New York.

Museum of Modern Art

2004 Roth Time: A Dieter Roth Perspective.

http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2004/dieterroth/flash.htm

Rebecca O’Dwyer

2010 The Iterable Gesture: A Study of Contemporary Strategies of Re-enactment. Unpublished Thesis proposal submitted to the Faculty of Visual Culture in Candidacy of the MA Art in the Contemporary World (NCAD).

Michael Thompson

1979 Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value. Oxford University Press, New York.

Gillian Whiteley

2010 Junk: Art and the Politics of Trash. I.B. Tauris, London.

Images

Kipp Normand images Central State and Trespasser courtesy Harrison Center flickr page For more information, visit the Harrison Center for the Arts

Cathedral of Junk image courtesy m-gem For more on the Cathedral of Junk, see Roadside America

Center for Environmental Education Plastic Bag art image courtesy sielju

Cologne Trash army Schult image courtesy Julia Janßen For more on the image, visit Schult’s wikipedia entry

Fanfare for Bill Cook image courtesy Indiana Landmarks

Consuming Geeks: Subculture and the Marketing of Doctor Who

This month the most committed Doctor Who fans descended on the Los Angeles Marriott for Gallifrey One, the 24th annual gathering of Whovians in Los Angeles. On the one hand, these Doctor Who fans share a commonplace geek satisfaction with their sense of distinction from the mainstream. A Who fan who grew up in Detroit noted that “As kids we loved anything Science Fiction from Star Trek to Space 1999 … we were weirdoes. But that was okay. It was a badge of honour. Really. SF was not as `popular’ then as it seems to be now, and British SF was probably deemed even odder.” Patton Oswalt’s analysis of contemporary geeks inventories a typical range of geek obsessions confirming that “I was never going to play sports, and girls were an uncrackable code. So, yeah—I had time to collect every Star Wars action figure, learn the Three Laws of Robotics, memorize Roy Batty’s speech from the end of Blade Runner, and classify each monster’s abilities and weaknesses in TSR Hobbies’ Monster Manual.” Oswalt admits the satisfaction he got from “quietly being tuned in to something dark, complicated, and unknown just beneath the topsoil of popularity.”

On the other hand, though, Oswalt is among the observers who have prophesied the death of that very subculture, lamenting “Fast-forward to now: Boba Fett’s helmet emblazoned on sleeveless T-shirts worn by gym douches hefting dumbbells. The Glee kids performing the songs from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. And Toad the Wet Sprocket, a band that took its name from a Monty Python riff, joining the permanent soundtrack of a night out at Bennigan’s. Our below-the-topsoil passions have been rudely dug up and displayed in the noonday sun.”

Once utterly invisible outside a circle of the most committed fans, in 2012 Entertainment Weekly heralded Doctor Who as a “global geek obsession”; this week al-Jazeera bought three seasons of Doctor Who; and in 2011 Doctor Who’s sixth season was the most downloaded television season on iTunes. In some observers’ minds, this long-awaited ascent to mainstream popularity spells the death rites for the Doctor Who geek as a distinctive voice and identity. Contemporary Doctor Who fans risk being not marginal at all, and in this respect they share quite a lot with comic books fans, science fiction geeks, anime fans, or role-playing gamers who all have secured significant footholds in popular culture: San Diego Comic-Con is now among the most influential of all mass media and marketing events; television is littered with a variety of series that openly invoke science fiction and celebrate geeks; anime and manga aesthetics pervade popular culture; and role playing games have become a massive industry whose impression can be seen all over popular culture. Once embracing something esoteric and disinteresting to the masses, geeks now have effected a complete reversal that witnesses them as the leading edge of style: rather than being disparaged as outcasts, geeks have become an energizing fringe fueling mass culture.

“Geek” is commonly referred to as a “subculture,” but that term is sloppily wielded in popular usage and tends to refer to nearly any distinctive social collective. In scholarly terms a subculture reflects and expresses social contradictions through oppositional style and social practice. Subcultures use material style and social practice to express and attempt to resolve the contradictions of mainstream culture: that is, weeping angel t-shirts, “Bad Wolf” bumper stickers, and sonic screwdrivers are utterly politicized symbols signaling social identity and distance from mainstream social codes. Doctor Who fans, like most members of self-identified subcultures, are energized by their self-perceived marginalization, if not the belief that they have been denied some unfettered experience by the normative values of “mainstream” society.

Not every geek is eager to relinquish their distinctions from the mainstream. Blogger Maryann Johanson, for instance, prophesied the underside of Doctor Who’s broader following when she lamented retailer Hot Topic’s embrace of Doctor Who merchandise: “Hot Topic is a U.S. chain store that pops up in malls to serve kids who want to buy a premanufactured notion of cool instead of developing their own personalities. If the vice president and general merchandise manager for Hot Topic is excited about Doctor Who, it can only mean that the Doctor is on the verge of tedious ubiquitousness in America.”

Johanson seems to be apprehensive that the unfeigned passion fans have invested in Doctor Who will be undone by the marketplace. Her wariness of “premanufactured cool” suggests the marketplace will inevitably redefine consequential if not deviant symbolism and reduce it to transparently commodified edginess. This is precisely what Dick Hebdige cautioned was the universal fate of subcultures. Hebdige’s classic study of punk style argued that subcultural aesthetics are re-defined by marketers in ways that neutralize anxiety-invoking distinctions. Those subcultural material forms—goth makeup, Rastafarian garb, hippie tie-dye shirts–become simply an aesthetic expressing no especially substantive social or political statement. Indeed, Hot Topic reduces fringe symbolism to a hollow style: pre-distressed shirts featuring the likes of Black Sabbath, David Bowie, or Joy Division evoke a historical fringe; pre-shredded jeans labor to conceal their wearer’s bourgeois status; and Batman earbuds invoke all the style and none of the pathos of the Caped Crusader.

Yet Hot Topic is far from the only company to charge into Doctor Who marketing. The founder of Her Universe—“a place for fangirls to step into the spotlight and be heard, recognized and rewarded”–told the Today show that Who merchandise was selling briskly, admitting that “`I never thought I would see it grow this much. … Girls would come up to me saying they wanted ‘Doctor Who’ shirts and I didn’t know how I could make it work logistically with the BBC in London.” But she was approached by BBC Worldwide’s own aggressive marketers because, according to their Director, “`She has a pulse on this demographic and on knowing what girls want.’”

The flood of Doctor Who merchandise reaching from toys to t-shirts to aquarium Daleks may indeed confirm that Doctor Who has been reduced to an aesthetic targeted to a particular consumer “demographic.” Doctor Who looms in this picture as an ambiguous symbol of aesthetic distinction; in contrast, geeks embrace something symbolically esoteric that is outside the mainstream. For some nervous fans, the passion they feel for Doctor Who or any other geek symbol hazards appearing irrelevant in the face of marketers’ dedication to profit.

However, it may be exactly the opposite: that is, perhaps the geek has now become valued by marketers precisely because geeks identify those social and stylistic niches into which people invest deep feelings. This no longer frames the geek as a unique entity, a stereotypically obsessive fan without connections to broader popular cultural discourses or politics. In an essay in Guerrilla Geek, Rory Purcell-Hewitt argues for something he dubs a “post-geek” that is quite along these lines. This post-geek is an assertively hybrid identity that does not fix geeks’ position within a particular subcultural niche: “the post-geek is one who has stepped beyond the barriers of the geek subculture, openly embracing philosophies and aesthetics from a multitude of cultures.” Contemporary geeks do indeed routinely poach on a rich range of popular cultural symbols—simply survey the cross-fertilization of symbols in Doctor Who shirts such as “Doctor Pooh,” “Gallifrey Road,” or “Doctor’s Eleven” that cannibalize other popular cultural geekery. That symbolic hybridity includes fans’ (and marketers’) conscious references to the show’s historical canon: Doctor Who evokes a half-century of programming and a distinctive retro aesthetic that the BBC’s avalanche of Doctor Who merchandise and DVDs routinely links to the newest episodes and storylines. This hybridity may be the geek’s elimination of their own uniqueness; that is, geeks and other subcultures are no longer isolated entities but wired hybrids thieving style and meaning from a range of discourses.

Doctor Who’s ascent to mass popularity certainly was fueled by the collapse of once-formidable barriers to Doctor Who access: much of Doctor Who’s run came in the context of a pre-cable TV world, the absence of mass-produced VHS tapes or VHS players, divides between the UK and US programming, and fandom organized around communities communicating through local clubs, modest conventions, and fanzines. Today, in contrast, a vast range of programming and linked marketing are accessible to nearly anybody with computer and/or cable access; BBC is systematically releasing every shred of Doctor Who programming on DVDs alongside branded books, audiobooks, and magazines; Who fans gather at massive conventions like Chicago TARDIS, Lords of Time (Australia), Regenerations (Swansea), and the official convention in Cardiff; fan communities are exceptionally well-connected online in sites like Gallifrey Base; and an enormous volume of online retailers specialize in commodities that are somehow cast as “geek.”

Subultures are not resisting any clearly defined mainstream, because normative social and stylistic codes are simply too dynamic and reside in ideology more than practice. Many geeks, though, hold onto the caricature of a normative mainstream to rationalize zealously guarding their unique identities, castigating newcomers as poseurs and warily patrolling the boundaries of the authentic canon. Perhaps the flood of Doctor Who DIY-er goods are the vanguard of material authenticity, or seeing the original Doctor Who late at night on a fuzzy black-and-white TV grants some fans some experiential privileges. But there was of course never a moment of “authenticity” untouched by the media, since Who fandom is based on a mass media product. Contemporary consumer culture is perhaps no longer populated by distinct collectives crafting individual styles in isolation; rather, we live in a world of heterogeneous styles in which appearances of resistance, deviance, and rebellion are simply a fashion. Geeks may be the preeminent creative spirits in such a moment, distinctive for their capacity to find the symbolically rich niches in mass culture like superheroes, Battlestar Galactica, and Doctor Who.

Piers D. Britton and Simon J. Barker

2003 Reading Between Designs: Design and the Generation of Meaning in The Avengers, The Prisoner, and Doctor Who. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Dick Hebdige

1979 Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Methuen, New York.

Matt Hills

2010 Triumph of a Time Lord: Regenerating Doctor Who in the Twenty-First Century. I.B. Tauris, London.

David Layton

2012 Humanism of Doctor Who: A Critical Study in Science Fiction and Philosophy. McFarland

Jefferson, North Carolina.

David Muggleton

2000 Inside Subculture: The Postmodern Meaning of Style. Berg, New York.

Steve Redhead, Derek Wynne, Justin O’Connor (eds.)

1998 The Clubcultures Reader: Readings in Popular Cultural Studies. Blackwell, New York.

John Tulloch and Henry Jenkins (eds)

1995 Science Fiction Audiences : Doctor Who, Star Trek, and Their Fans. Routledge, New York.

Peter Wright

2011 Expatriate! Expatriate!: Doctor Who: The Movie and Commercial Exploitation of a Multiple Text. In British Science Fiction Film and Television: Critical Essays, eds. Tobias Hochscherf, James Leggott, and Donald E. Palumbo, pp. 128-142. McFarland and Company, Jefferson, North Carolina.