Monthly Archives: May 2013

Geek Ink: Geek Tattoos and Consumer Culture

To be geek is no longer an especially unique or stigmatizing proclamation. The term geek is often somewhat sloppily used to refer to a broad range of people with some fervent attraction to something; while it is not necessary to establish an inflexible definition for geek, it seems to distinguish social groups sharing a fervent collective commitment to fan practices and discourses: those might revolve around comics, science fiction, gaming, or nearly any other dimension of popular culture that fashions social interactions and consumption.

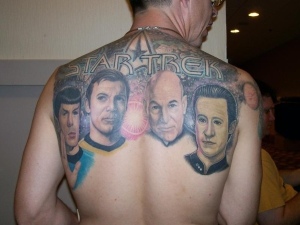

In the context of consumer culture being geek risks losing its distinction as marketers package geek symbols for the masses, so geeks aspire to race ahead of the “mainstream,” seeking out the creative, arcane, and specialized and preserving geek distinction before it falls victim to mass marketing. The challenge contemporary subcultures face is to maintain social practices and material style in opposition to a homogenizing marketplace that reduces such practices and things to mass-produced—and commonplace–commodities. Batman, Star Wars, Star Trek, and Spiderman are now brands in the sense that they may be homogenizing marketing symbols as much as they are symbols of distinction or resistance.

Geeks’ distinction is not simply a matter of material consumption: geek standing is secured by informed thinking through and mastery of obscure knowledge, so it is fundamentally social. The notion that such social practices define a “geek culture” risks lapsing into marketing caricatures, and it also hazards a contrived authenticity that poses absolute boundaries between geeks and non-geeks. Nevertheless, there are some genuine social distinctions, and consumption is clearly a key dimension of staking a claim to geek status, with a variety of material culture—t-shirts, toys, posters, shoes—offering up geek symbols recognizable to nearly any audience.

Tattoos are commodities that embed symbolic capital in our skin, rendering our body a consumable sign to be “read,” however tattoos are distinctive consumables. On the one hand, tattoos are commodities that routinely represent popular cultural motifs if not branded symbols, and tattoos no longer represent dramatic deviance from the mainstream (21% of American adults in 2012 had at least one tattoo). On the other hand, tattoos are not mass-produced commodities, and they represent some individually chosen symbolism. Tattoos fabricate consumer selfhood, but they involve individual selection of the symbols, a narrative of the process of getting the tattoo, and genuine permanence.

Science fiction and comics provide many rich franchise symbols. Batman, for instance, provides a host of Bat logos and symbols from comics, the television show, a series of movies, and even games. Like the most cherished sci-fi and comic franchises, a Batman symbol is recognizable beyond the confines of geek circles, but that broad currency risks undermining the symbol’s geek meanings. A geek tattoo is most powerful as subcultural capital when it invokes a novel or obscure symbol distinct to a subcultural collective; in a geek’s skin, these deepest symbols materialize knowledge, creativity, and devotion, if not love.

Much like Batman, Doctor Who provides a host of symbols including the TARDIS, Daleks, K-9, and the Doctors as well as a host of catchphrases for the textually inclined. After over a half-century of programming, Doctor Who symbols are familiar amongst geeks, and a completely unscientific survey of online Who tattoos suggests that the TARDIS is indeed the most common motif amongst Who tattoos. The TARDIS has the attraction of providing a form a consumer and tattoo artist can individualize, and being a literal shape that fits nicely along various reaches of the body, including backs, arms, ankles, calves, and even the lower back.

This TARDIS tattoo wraps itself in the Fourth Doctor’s iconic scarf (image Jon Reed, All Saints Tattoo Austin TX).

A TARDIS tattoo has widespread apprehensibility, yet at some point it risks becoming so commonplace that it loses its novelty. A tattoo hazards losing its claim to subcultural and artistic authenticity as well as its individual distinction if it simply reproduces a mass motif or invokes celebrity. Batman’s masked hero makes little appeal to the personality of Bruce Wayne or the actors who have played the Caped Crusader, and Star Wars provides similarly de-personalized characters like Darth Vader, Ewoks, or the Death Star. Nevertheless, in some cases it is difficult to separate a personality from a character (e.g., Heath Ledger’s Joker), and some celebrities like Marilyn Monroe may function symbolically as characters more than homages to celebrity. Doctor Who tattoos sometimes pay homage to the Doctors (e.g., the iconic fourth Doctor Tom Baker, or even all the Doctors). The most recent Doctors (David Tennant and Matt Smith) appear in some tattoos as symbols of “geek chic,” a self-consciously geek fashion that has become closely associated with both Tennant and Smith. However, as a concrete style geek chic aspires to take an unfeigned look and turn it into a superficial consumer aesthetic with no real claim to geek subculture. Unlike an original artistic motif, a popular symbol or a personality tattoo hazards losing geek consequence if its lack of aesthetic novelty undercuts the subcultural and personal meaningfulness of a tattoo.

The audience for a geeky tattoo is perhaps on some level other geeks or the uninitiated, but tattoos are not purely performative; that is, a tattoo in many ways is a soliloquy of selfhood as much as it is a display of geekhood. Tattoos establish bonds with like-minded others and materialize personal narratives, but they also are inchoate personal imaginings of who a consumer fancies themselves to be, rich evocative symbols of particular individual and social properties a consumer associates with a motif. A geek consumer articulates their sense of novelty, creativity, and personality to themselves in their commitment to a tattooed symbol that fashions themselves as “authentically” geek.

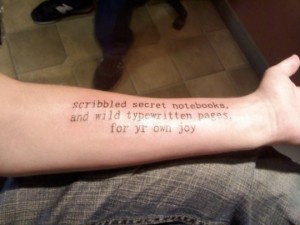

Where sci-fi, comic, and movie geeks raid popular cultural discourses for their tattoo symbols, literature geeks mine texts for quotations. Literary tattoos celebrate rich, evocative turns of phrase rather than abstract symbols, but they still have an aesthetic dimension, minimally in fonts but often in symbols paired with textual quotes. No literary tattoo seems more common than Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five quote “So it Goes.” The flexible phrase appears in the book over a hundred times, and it is especially attractive as a tattoo for its succinctness (so it can appear in many different body spots), and it invokes a classic cult novel. Like popular cultural tattoos, literary geeks’ tattoos demonstrate knowledge of a text, carefully negotiating between celebrating a too-familiar quote or finding one that is overly arcane.

The stereotype of an obscure, anti-social, style-less, and isolated geek culture has been undone by a consumer culture that markets geek style to and has more overlap with popular culture than most geeks acknowledge. The projection of that style beyond narrow geek circles sometimes strikes apprehension in the imagination of geeks aspiring to preserve their sense of material and social distinction. Tattoos aspire to capture that geek symbolism in ways that preserve its distinctiveness without lapsing into the appearance of consumer homogenization. What it means to be geek is utterly dynamic, contextual, and defined in constant social interaction and negotiation within and against mass marketing. Tattoos—personal, creative, idiosyncratic, permanent—provide one mechanism anchoring geek selfhood.

Some images take geek motifs like the Borg and project them onto other symbols, in this case creating an Abe Lincoln of Borg (image Geeky Tattoos)

References

Anders Bengtsson, Jacob Osterberg, and Dannie Kjedlgaard

2005 Prisoners in Paradise: Subcultural Resistance to the Marketization of Tattooing. Consumption, Markets and Culture 8(3):261-274.

Christina Goulding, John Follett, Michael Saren, and Pauline MacLaren

2004 Process and meaning in “getting a tattoo.” Advances in Consumer Research 31(1):279-284.

Paul Lopes

2009 Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Maurice Patterson and Jonathan Schroeder

2010 Borderlines: Skin, tattoos and consumer culture theory. Marketing Theory 10(3):253–267.

Victoria Pitts

2003 In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification. Palgrave Macmillan, Gordonsville, Virginia.

Enid Schildkrout

2004 Inscribing the Body. Annual Review of Anthropology 33(1):319-44.

William L. Svitavsky

2001 Geek Culture: An Annotated Interdisciplinary Bibliography. The Bulletin of Bibliography 58(2):101-108.

Jason Tocci

2007 The Well-Dressed Geek: Media Appropriation and Subcultural Style. Paper presented at MiT5, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Anne M. Velliquette, Jeff B. Murray, and Elizabeth H. Creyer

1998 The Tattoo Renaissance: An Ethnographic Account of Symbolic Consumer Behavior. Advances in Consumer Research 25:461-467.

Rebecca Williams

2011 Desiring the Doctor: Identity, Genre, and Gender in Online Fandom. In British Science Fiction Film and Television: Critical Essays, edited by Tobias Hochscherf and James Leggott, pp.167-177. McFarland and Company, Jefferson, North Carolina.

Amy Wilkins

2008 Wannabes, Goths, and Christians: The Boundaries of Sex, Style, and Status. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Image

Abe Lincoln of Borg image Geeky tattoos

David Tennant image from Nerd tattoos

Doctor Who villains image Geeky Tattoos

Jack Kerouac quote from Tips for Spontaneous Prose image from contrariwise

Star Trek tattoo image Tissy Tech

TARDIS and Fourth Doctor Scarf image Jon Reed by All Saints Tattoo

Time Seal image Benchilada

Yoda tattoo image Tissy Tech

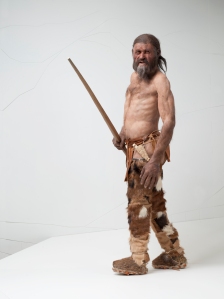

The Faces of Otzi: Imagining the Dead

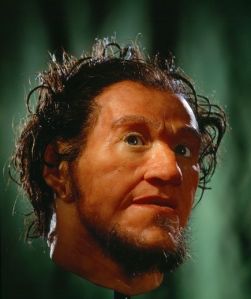

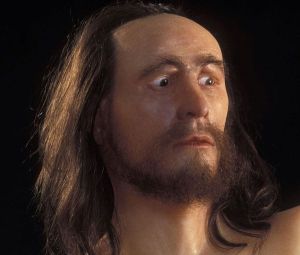

The newest Otzi reconstruction in the South Tyrol Museum (image Kennis © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Foto Ochsenreiter)

Few artifacts are more compelling than the twisted body of Otzi, the 5300-year-old man removed from Alpine snow in 1991. Archaeologically, Otzi is a unique snapshot of a life and a distinct moment, his assemblage revealing Copper Age materiality, his body telling the story of life in the Alps over five millennia ago, and his story illuminating a violent moment and a fascinating death story in which Otzi apparently met his end in a mountaintop murder. Otzi has been the subject of over 20 years of scientific investigation, archaeological discussion, and popular curiosity, and he is now celebrated in liqueur, snow globes, and assorted trinkets as well as an Otzi Village outdoor museum and a museum in which Otzi’s preserved body stares back at the curious. He has also been reconstructed continually for over 20 years, and that process underscores that facial and bodily reconstruction may invoke scientific accuracy but it is perhaps more about imagining human familiarities across the breadth of time.

Otzi’s five thousand years in the ice preserved him exceptionally well. Nevertheless, much like many other archaeologically recovered human forms such as unwrapped mummies, bog bodies, or skeletal remains, Otzi’s discolored and misshapen remains bear the unmistakable traces of human form—limbs, facial aesthetics, fingernails, toes—even as his distorted body aesthetically distances him from the present. Otzi is somewhat uncomfortably like us even as his millennia-old body betrays its distance from us in the present.

One way we can imagine Otzi’s story is through the series of facial and bodily reconstructions done over more than 20 years. Such reconstructions have become a staple of popular archaeological narratives: the unveiling of an anonymous teen cannibalized at Jamestown, Virginia featured a facial reconstruction; Richard III’s remains were shared in Leicester in February alongside a forensic approximation; the purported face of Alexander the Great’s father Philip II has been reconstructed with a disfiguring eye injury; and scans of French King Henri IV’s skull—removed from his grave in 1793 before being identified two years ago–were used to produce a facial reconstruction of Henri, who died in 1610.

Otzi has been interpreted with a surprisingly broad range of faces. A rich scholarly literature examines the specific methods used to reconstruct facial forms with skeletal remains, but most of it revolves around “accuracy” in some objective physical form. It is not clear that the reconstructions of Otzi or any of these other subjects need to stake a claim to absolute accuracy, though; instead, they illuminate the distance between past and present, particularly the archaeological artifact that displays its historical distance. On the one hand, the Otzi reconstructions over 20 years cast the same body in a vast range of forms and illuminate the methodological complications of accurate reconstructions; on the other hand, though, the many faces of Otzi may be more important as efforts to evoke and imagine an inaccessible human experience and fashion a subjectivity for this anonymous corpse.

Facial reconstructions are artifacts in their own right, distinctively neither archaeological things nor pure contemporary constructions. On some level reconstructions are simply emotionally evocative mechanisms that fashion a corpse or skeleton into some bodily familiarity. Facial reconstructions have no particularly concrete interpretive purpose except to evoke human familiarity. For instance, when the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology unveiled its new Otzi reconstruction in 2011, the museum’s director indicated that “This accurate yet sensitive representation of Ötzi will fascinate and stir people around the world. It gives our history a face, in the truest sense of the word.” Germany’s National Geographic editor celebrated the newly imagined Otzi, proclaiming that “now we can finally look him in the eyes and recognise, to our amazement, that he is really one of us!”

On another level beneath the somewhat shallow embrace of our common humanity, a reconstruction gives an artifact—a partial skeleton, a mummified body, a corporeal form otherwise stripped of its subjectivity–a human identity. In his analysis of the “personification” of Otzi, John Robb has argued that this is “our act of supplying what we feel to be the essential dimensions of any body which are missing here.” Otzi is an archaeological artifact who comes to us as an anonymous dead person whose personhood and story are animated by archaeological narrative and a facial or bodily reconstruction. Otzi’s skin and soft tissue make him an especially powerful symbol of such personhood, having recognizable material traces of humanity and rich archaeological evidence to weave a fascinating life story. The nameless Jamestown teen, in contrast, is a fragmented skeleton recovered outside a discrete burial context who could easily be depersonalized, but she has been wound into a compelling narrative about the boundaries of human desperation.

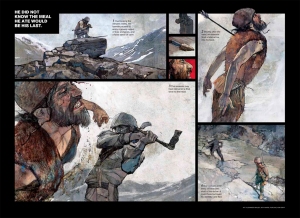

In 2008 a National Geographic editor suggested that such reconstructions “make some people, particularly scientists, squirm. Why? Because they are primarily art.” National Geographic itself featured a graphic novel style depiction of Otzi’s death drawn by Bulgarian comic artist Alex Maleev, but it weaves a story reasonably true to the archaeological analysis. In contrast, the reconstructions of Otzi are compelled to wield some measure of methodological and interpretive flexibility.

This National Geographic depiction of Otzi’s last moments was drawn by comic book artist Alex Maleev.

Archaeologists are probably not especially apprehensive of art as much as art weaves emotional, idiosyncratic, and fragmentary narratives that aesthetically and textually expand conventional archaeological interpretation. Facial and bodily reconstructions probably add little or nothing to our archaeological analysis, but they lend a powerful emotional dimension to the archaeological interpretation of a human body and life. Such narratives and facial reconstructions risk lapsing into ideologically distorted notions of individuality and focusing on a single life in isolation from a broader social and historical context. Nevertheless, reconstructions provide an interesting artifact that illuminates how archaeology breathes humanity into a corporeal artifact like Otzi, the Jamestown victim, and the scores of skeletal humans recovered by countless archaeologists.

References

Peter Acs, Thomas Wilhalm, and Klaus Oeggl

2005 Remains of grasses found with the Neolithic Iceman “Ötzi.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 14(3):198-206. (subscription access)

Roberta Ballestriero

2010 Anatomical models and wax Venuses: art masterpieces or scientific craft works? Journal of Anatomy 216(2):223-234.

Juan Gabriel Bridaa, Marta Meleddub, and Manuela Pulinac

2012 Understanding Urban Tourism Attractiveness The Case of the Archaeological Ötzi Museum in Bolzano. Journal of Travel Research 51(6):730-741. (subscription access)

Andy Coghlan

2012 Ötzi the ice mummy’s secrets found in DNA. New Scientist 213(2854):10. (subscription access)

Walter F. Kean, Shannon Tocchio, Mary Kean, and K. D. Rainsford

2013 The musculoskeletal abnormalities of the Similaun Iceman (“ÖTZI”): clues to chronic pain and possible treatments. Inflammopharmacology 21(1):11-20. (subscription access)

Andreas G. Nerlich, Beatrice Bachmeier, Albert Zink, Stefan Thalhammer, and Eduard Egarter-Vigl

2003 Ötzi had a wound on his right hand. The Lancet 362(9380):334.

John Prag and Richard Neave

1997 Making Faces: Using Forensic and Archaeological Evidence. Texas A & M University Press, Austin.

Alois G. Puntener and Serge Moss

2010 Otzi, the iceman and his leather clothes. CHIMIA International Journal for Chemistry 64(5):315-320. (subscription access)

John Robb

2009 Towards a Critical Otziography: Inventing Prehistoric Bodies. In Social Bodies, edited by Helen Lambert and Maryon McDonald, pp 100-. Berghan Books, New York.

C.N. Stephan

2005 Facial approximation: a review of the current state of play for archaeologists. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 15(4):298-302. (subscription access)

Laura Verzé

2009 History of facial reconstruction. Acta Biomed 80(1):5-12.

Caroline Wilkinson

2004 Forensic Facial Reconstruction. Cambridge University Press, New York.

2010 Facial reconstruction–anatomical art or artistic anatomy? Journal of Anatomy 216(2):235-250.

Graphics

Otzi South Tyrol image Kennis © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Foto Ochsenreiter

Otzi comic image from National Infographic

Otzi Museum image South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology

Bourgeois Brew: The Landscapes of Craft Brewing

The landscape of contemporary bourgeois materiality is dotted with a legion of craft breweries, microbreweries, and brewpubs busily fermenting myriad new recipes targeting the upwardly mobile palate. The consumers of these modest breweries are increasingly well-versed in beer styles, the ingredients and chemistry of brewing, and the distinctions of regional styles and particular breweries. We are now in the midst of American Craft Beer Week, which is being celebrated May 13-19, and this celebration of handcrafted beers illuminates bourgeois consumption patterns, the idiosyncracies of bourgeois taste and style, and even the politics of craft beer consumption.

The bourgeois that have descended on craft breweries encompass a broad swath of social groups whose consumption revolves around material taste and stylistic distinction. This effort to craft distinction in material things is not especially uncommon, but bourgeois consumption tends to avoid shows of sheer affluence itself; that is, novelty, an appeal to progressive rationality (e.g., shopping green), and perceived individual stylistic distinction drive contemporary bourgeois consumption. This picture of bourgeois consumption stands idealistically opposed in the bourgeois imagination to the homogeneity, function, and thrift that fuel mass consumption, and the tendency to avoid shows of wealth stands opposed to the pretentious material affluence associated with the uber-wealthy (compare the counter-cultural capitalists David Brooks calls “bourgeois bohemians.”) To be bourgeois is to possess refined tastes even in the absence of genuine affluence, so it is not purely a show of material wealth as much as it is both material and social capital shaping consumption. Consequently, this definition of the bourgeois could reasonably include upwardly mobile yuppies, hipsters, indebted university students, and older educated urbanites.

Artisan foods from cheeses to chocolates have secured a market foothold by appealing to the educated palate, and beer appears to have been especially successful securing a place in bourgeois and aspiring bourgeois foodways. In March, 2013 the US had 2,360 craft breweries (which includes 1124 brewpubs, 1139 microbreweries, and 97 regional craft breweries). The central challenge for these small breweries is simply to dent consumer consciousness in a marketplace crowded with designer porters, and breweries wield a variety of symbolic mechanisms to secure consumers’ cultivated palettes. Bourgeois taste cherishes novelty and the symbolic capital derived from demonstrating mastery of beer knowledge and being an early adopter of a particular brew. Much of the microbrew rhetoric points to the cultivation of such discerning palettes, a mechanism that fashions bourgeois drinking as educated and individual. The Brewers Association, for instance, suggests that the “hallmark of craft beer and craft brewers is innovation. Craft brewers interpret historic styles with unique twists and develop new styles that have no precedent.” They stress that “Craft beer is generally made with traditional ingredients like malted barley; interesting and sometimes non-traditional ingredients are often added for distinctiveness.”

Some brewers paint themselves as fringe firms, hoping to evoke some of the imagined outsider status consumer subcultures routinely cherish. The Lagunitas Brewing Company’s offerings, for instance, include “Censored” ale: “Originally called the Kronik, this beer was censored by the federal label-approving agency … they claimed the word had some sort of Marijuana reference. We slapped a `Censored’ sticker on it as a joke and they accepted it.” Lagunitas crafts a distinctively independent California personality, indicating their mission has been “driven unseen by an urge to communicate with people, to find our diasporidic [sic] tribe, and to connect with other souls adrift on a culture that had lost its center and spun its inhabitants to the four winds to wander lost and bereft with a longing to re-enter the light. Beer, we have learned, has always been a good lubricant for social intercourse!” Other breweries hope to secure out attention with a cleverly named brew: Indiana’s 3Floyd’s Brewery makes a “gushy undead” pale ale it calls “Zombie Dust”; California’s Buffalo Bills Brewery offers up “Alimony Ale”; and Middle Ages Brewing Company makes a barleywine it calls “Druid Fluid.”

Chicago’s Wicker Park touts itself as having “the most complete set of beer oases in Chicago.” The neighborhood celebrates the presence of two “cicerones” amongst these craft bars (a beer consumers’ version of a sommelier), both of whom have been certified to have “the knowledge and skills to guide those interested in beer culture, including its historic and artistic aspects.” The cicerone certification identifies “a person with demonstrated expertise in beer who can guide consumers to enjoyable and high-quality experiences with great beer.” One of these cicerones lords over Bangers and Lace, a bar and restaurant “with the feel of a Midwestern lodge” that serves up bangers (i.e., sausages) and lace (i.e., the “Brussels lace” foam that clings to a beer mug). The nearby Moonshine brewpub likewise touts their brewmaster. Moonshine accents his “outsider” status by dubbing him a “renegade brewer” and underscores his brewing skills by noting that he “studied at North America’s oldest brewer’s academy, Siebel Institute, as well as the world-renowned Doemens brewer’s academy in Germany.”

Boutique beers are often difficult to find and more expensive than macrobrews, but craft beer is in many consumers’ minds a more economical option than options such as wine. A drinker at the Lagunitas Brewing Company told AdWeek that “for five or six dollars, we’d rather drink really good beer than mediocre wine.” This fashions craft beer more as a reflection of an educated palette than affluence alone. Simultaneously, craft beer is fashioned in somewhat contradictory forms as part of an “every-man’s” tradition of drink, which clumsily situates craft brews in a working-class heritage. This runs somewhat counter to craft breweries’ tendency to frame consumption as a reflection of cultivated individual taste; where working class drinking fosters homogeneity, bourgeois consumption celebrates novelty and individual discernment distinguishing the consumer. This contradiction awkwardly negotiates bourgeois consumers’ own acknowledgement of their social and material homogeneity; even as they drink a novel IPA and embrace a distinctive sense of style, they share dress, taste and values.

Among the most distinctive of craft beer names is Clown Shoes Beer’s Tramp Stamp pale ale (image Clown Shoes Beer).

Craft brewers invoke “community” in a variety of somewhat ambiguous ways that evade the distinct class of consumers who patronize such breweries. A January, 2013 survey found that “fully half of craft beer devotees are interested in locally made beer, while 25 percent are interested in purchasing craft beer only where it’s brewed.” Indianapolis’ Triton Brewing Company celebrates its values of being “a creative outlet in the form of a traditional, community-based production brewery located in the heartland of Indiana. The shareholders, employees, and libations of Triton Brewing Company embody exemplary strength of character, resolute integrity, and consistent quality in all their forms.” The Brewers’ Association likewise celebrates their local connections, indicating that “Craft brewers have distinctive, individualistic approaches to connecting with their customers.” The Lagunitas Brewing Company’s founder indicates that “What will help us in the long run is that essentially we are not in the same business as the multinational brewers. We are selling community, and they are selling liquid.”

Many craft breweries root themselves in a place through historical reference. San Francisco’s 21st Amendment Brewery cleverly links their business to the city’s early 20th century heritage, when “there were about 40 breweries operating just within the city limits.” Those breweries were “the local gathering places. Places to exchange ideas, debate politics and philosophy. Places for families to come together on weekends. Places that provided something unique—hand crafted beer that was different at every brewery and that defined the taste of a neighborhood. In 1920, Prohibition wiped out this culture and put the `local’ out of business. … But with the passage of the 21st Amendment, repealing Prohibition, we, as a society, were able to begin the slow climb back to reclaiming the essence of the neighborhood gathering place. At the 21st Amendment, they celebrate the culture of the great breweries of old, making unique, hand crafted beers, great food, and providing a comfortable, welcoming atmosphere that invites conversation, interaction and a sense of community.” Like 21st Amendment, FEW Spirits is an Evanston, Illinois distillery that plays on prohibition history by taking takes its name from Evansville temperance reformer and suffragist Francis Elizabeth Willard.

Craft breweries are a common feature of the contemporary upwardly mobile urban landscape. For instance, Chicago once had more than 50 Schlitz “tied houses,” pubs that sold beers from just one brewery, and many now house new businesses in urban neighborhoods. Increasingly more breweries are being turned into homes, commonly marketed as “brewery lofts.” Los Angeles’ Brewery Arts Complex, for instance, is a former Pabst Blue Ribbon plant that was re-tooled into homes and studio spaces that are rented only to artists. The E&B Brewery Lofts in Detroit are residential lofts in the former Eckhardt and Becker Brewery, which operated in the building from 1891 to 1969 and now also houses the Red Bull House of Art. The Gund Brewery Lofts in LaCrosse, Wisconsin break from the model of brewery lofts as artists’ havens, instead offering low-income housing.

Batch 19 plays off Prohibition heritage and drinking as a forbidden pastime, but the beer is made by macrobrewery Coors.

The craft breweries’ modest share of the American marketplace belies the appeals of craft beers that potentially reach well beyond even a broadly defined bourgeois. This week the Das Ale Haus blog reported on the faux craft label beers produced by macrobreweries intent on securing an ever-expanding slice of America’s alcoholic palette. For instance, labels like Goose Island and Blue Moon borrow from much of the symbolism and advertising rhetoric of craft breweries but are owned by Anheuser Busch and Molson-Coors, respectively. Where craft beers may have mastered a certain narrative that macrobrewers are eager to capture, macrobreweries have the profound advantage of marketing and distribution networks and the capacity to sell their products at low prices. Yet the macrobreweries face declining domestic and imported beer sales while craft beer profits steadily increase, and craft beers have secured much of their success from young consumers: A 2013 study found that consumers aged 25-34 are craft beer’s primary market, with 50% of the demographic consuming craft beer, and 43% of millennial and Gen X consumers prefer the taste of craft beer to domestic. The same study concluded that the craft beer market of $12 million in 2012 will reach $18 billion by 2017, international markets such as Australia reflect similar trends.

Images

Clown Shoes Tramp Stamp label image courtesy Clown Shoes Beer

Durham Craft Beer image courtesy lpolinski

Elysian Brewing label image courtesy firstwefeast.com

Schlitz tied house image courtesy kendoman26

Shipyard Brewing Company image courtesy brentdanley

Consuming Marginality: An Archaeology of Hipster Materiality

This weekend I am in Chicago at the Theoretical Archaeology Group conference and delivering this paper examining the relationship between identity in post-segregation society and the legions of contemporary groups that see themselves as marginal. This revisits some of the issues I raised in my December 2012 post on hipsters but focuses on the relationship between, on the one hand, the erosion of ideological frameworks for identity—Blackness in particular, but also patriarchy, middle class, and urbanity—and, on the other hand, contemporary consumer collectives like hipsters that willingly embrace “marginality.”

In 1957, Norman Mailer lamented the hipster, the White youth who had become alienated to a society that had delivered depression, global war, the threat of nuclear apocalypse, and stultifying post-war homogeneity. Mailer argued that for these disillusioned Cold War hipsters, “the only life-giving answer is to … divorce oneself from society, to exist without roots.” Mailer dubbed the hipster “the White Negro,” because these disaffected White youth ostensibly divorced themselves from bourgeois discipline and appropriated African-American dress, music, and style, finding an “authentic” emotional experience in African American life. Mailer suggested that “in this wedding of the white and the black it was the Negro who brought the cultural dowry. Any Negro who wishes to live must live with danger from his first day, and no experience can ever be casual to him.” Mailer suggested that Whites were fascinated by Blacks’ unfettered emotion in the face of totalizing marginalization and felt similarly oppressed by a “slow death by conformity.”

From the vantage point of early 21st-century post-segregation consumer culture, the rejuvenated specter of the hipster again evokes marginalization and the quest for authenticity. Popular observers commonly reduce contemporary hipsters to a hollow caricature or see nothing especially consequential in yet another fringe social collective, but hipsters reflect the collapse of essentialized identities once anchored by the likes of racial subjectivity. In the vacuum created by the assault on race, masculinity, and the bourgeois, the hipster is a symptom of a widespread desperation to secure renewed authenticity once provided by those very ideologies. During the Cold War Mailer suggested that hipsters divined such authenticity in African American life, which posed a dramatic break from White bourgeois materialism and post-war homogeneity. Sociologist Ned Polsky was among the observers who argued that such a break simply thieved diasporan style and culture, arguing that “in the world of the hipster the Negro remains essentially what Ralph Ellison called him–an invisible man.” Yet hipsters did not simply appropriate African diasporan culture; rather, hipster culture crystallized Whites’ perpetual romantic fascination with the unfeigned authenticity of Black emotional experience and confirmed White envy of Black survival in the face of totalizing marginalization.

In the midst of a post-segregation society more than a half-century later, contemporary hipsters stake out a position that remains rooted in marginality, but they appear to have been joined by the breadth of American society in their claim to peripheralization. Cold War and contemporary hipsters share a common subcultural impulse to distinguish themselves through material style, but seemingly the full breadth of contemporary society has carved out its own stylistic niches. The erosion of racial, patriarchal, and bourgeois subjectivity has produced a very distinctive 21st-century hipster alongside a host of other social subjects—doomsday preppers, the Tea Party, the Occupy movement–seeking some substantial foundation for selfhood that expresses their experiences and ambitions. “Seeing” marginality is no longer especially challenging; indeed, archaeologies that aspire to “see” distinctive marginality risk reproducing an essentialism that Cold War White hipsters and Norman Mailer imposed when they romanticized Black emotional authenticity and racial experience. James Baldwin tempered such romanticism over the hipster’s creative construction of self when he argued that “a Negro man … had to make oneself up as one went along … in the not-at-all metaphorical teeth of the world’s determination to destroy you.” The challenge is to “see” structural processes of marginalization in everyday material life without lapsing into a romanticized picture of myriad socially marginal groups creatively crafting their authenticity.

Like many fringe groups before them, contemporary subcultures feel somehow alienated to an ambiguous “mainstream.” That mainstream may always have been more ideological than objective reality, and the perceived descent into universal marginality is at best contrived. However, the mainstream was long anchored by ideological bedrocks like Black difference that have now been unraveled by 21st-century hybridity, even as we remain persistently attached to material and cultural distinction; the hipster is simply one collective amongst us aspiring to craft a position in a society that seems hostile to our distinctive ambitions. Once a contested power relationship that produced distinction through concrete structural inequalities, marginality is now celebrated for its animation of consumer creativity and self-identification.

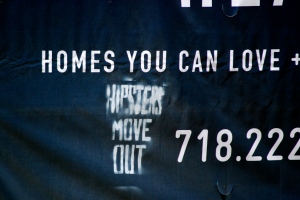

Precisely what defines a hipster today is ambiguous, and it is as much a slur, a transparent ideological notion, a youth culture demographic, and a marketing category as it is a coherent social subjectivity. The contemporary stereotype of hipsters revolves around materiality: for instance, hipsters wear vintage clothes from thrift shops or retro style from chains like Urban Outfitters that manufacture patina, and they accent such clothes with Chuck Taylors and Wayfarers; they embrace “low-brow” materiality like drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon or smoking European cigarettes to disguise their class standing; and like all subcultures they are fervent music consumers. Richard Florida suggests that these youth live in “hipster havens” like Wicker Park and Williamsburg, which, in his words, “attract a relatively affluent crowd—that doesn’t want to appear too affluent.” Yet these characterizations are in many ways simply a social caricature if not a marketing category that through popular repetition aspires to assume its own authenticity (for a compelling study of Wicker Park, see Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City)

A Wicker Park shop window appeals to the hip who live in the Chicago neighborhood (image avrenim_acceber).

It would be easy to dismiss hipster discourses as superficial fashion critiques, but the anxieties over present-day hipsters betray more deep-seated apprehensions over the shallowness of contemporary consumer politics. Christy Wampole’s New York Times piece “How to Live without Irony” laments the superficial materiality of the hipster, who “tries to negotiate the age-old problem of individuality, not with concepts, but with material things.” This critique romanticizes a counter-culture steeped in intellectual creativity, strategic politics, and some sort of common politicizing experience, but this idealized activism is an awkward fit to 21st-century society: the “mainstream” is an ambiguous if not ideological target; and the guise of authentic, shared oppression fueling strategic politics idealizes collective resistance. Wampole and many other observers remain romantically attached to a notion of “pure, unfettered subjectivity” in which human agency places us outside relations of power and marginalization, a position from which critical political activism is launched against marginalizing mainstreams.

Hipster materiality mines the detritus of dead aesthetics to craft contemporary distinction, but many observers dismiss such consumption as pallid mimicry of historical styles. In 2008, for instance, Adbusters’ Douglas Haddow theatrically lamented, “An artificial appropriation of different styles from different eras, the hipster represents the end of Western civilization – a culture lost in the superficiality of its past and unable to create any new meaning.” Under the hateful banner “the Hipster Must Die,” Christian Lorentzen similarly complained that “hipsterism fetishizes the authentic and regurgitates it with a winking inauthenticity.” Yet hipsters’ tactical fabrication of style from the shreds of popular culture may be what we all have done across the breadth of consumer society: that is, we all fancy ourselves creatively reconfiguring the commercial symbolism pinned on brand goods, store devotion, seasonal styles, and popular culture instead of inheriting our sense of self from art, faith, and Culture. The former are dismissed as inauthentic and meaningless, but hipsters may be mining those historical symbols consciously recognizing they are hollow; that is, it may well be that the appropriation of “dead,” once-authentic styles is in fact intended to signify nothing concrete beyond the idiosyncratic display of material style.

Such styles emptied of their historicity may be what Fredric Jameson referred to as the “perpetual present” in which “all that is left is to imitate dead styles.” Individualized creativity lies at the heart of contemporary hipster materiality, yet it does risk coming in the absence of especially concrete collective consciousness. Where the Cold War hipster fetishized the electric vitality of unfiltered Black emotional experience, the contemporary hipster may be seeking the fantasy of unfettered creative expression in the face of mass cultural conformity. Such individual creativity is then subject to the withering and unpredictable logic of hipster taste, which is geared to idiosyncratic aesthetic novelty and emotive instinct more than rationality, historical reference, or a concrete notion of stylistic politics.

Despite the absence of concrete hipster standards, the hipster risks serving consumer capitalism as a stylistic arbiter for mass culture. Indeed, marginal collectives from Metal fans to Whovians to hippies have become the foot soldiers for mass marketers, divining novelty from the subcultural fringes and delivering it to marketers. Hipsters, for instance, fixate on retro style and patina that pervades the contemporary marketplace. Rather than outsiders, hipsters instead loom as marketing mercenaries in a world of heterogeneous styles in which resistance, deviance, and rebellion are handed over to mass culture and reduced to consumable fashions.

Observers critical of de-historicized hipster retro persistently accuse hipsters of in-authenticity. Douglas Haddow, for instance, laments that hipsters are “a lost generation, desperately clinging to anything that feels real, but too afraid to become it ourselves. We are a defeated generation, resigned to the hypocrisy of those before us, who once sang songs of rebellion and now sell them back to us. … The hipster represents the end of Western civilization – a culture so detached and disconnected that it has stopped giving birth to anything new.” In this overwrought moralism, the hipster is the symptomatic tip of a mass cultural iceberg that has become stalely self-referential, utterly insincere in its politics and emotions, and alienated to a public life.

Yet perhaps hipsters are not imitating marginality as much as they are willfully inhabiting it and claiming the crowded fringe as an empowering social position. This is in some ways like the break their peers hoped to make from Cold War homogeneity when they embraced Black marginality and feeling. However, the fantasy of “being Black” was at best an awkward fetishization; while it took aim on race by recognizing marginalization as a social process and not an essential identity, only Whites enjoyed the privilege of performing Blackness across the color line.

There is a lesson here for archaeologies of marginality that presses us to push beyond essentialization even as we acknowledge the power of such categories, the allure of material distinction, and the tension of “mainstream” social mores. Archaeology illuminates marginalization processes, not simply marginal peoples: contemporary cityscapes, for instance, are the legacy of racist urban renewal programs with lasting effects touching dispossessed African Americans as well as transplanted hipsters. Rather than articulate the challenge as “seeing” marginal peoples in these past and present landscapes, perhaps the question is instead how to problematize a romantic notion of alienation that allows us to imagine ourselves apart from a social mainstream. Alienation allows us to fantasize an authentic self who can somehow be made “visible” in the midst of totalizing marginality, which risks evading the social and ideological construction of selfhood: Mailer’s hipsters, for instance, remained White despite their earnest desire to repudiate “every social restraint and category.”

In this sense, contemporary hipsters offer a particularly interesting 21st-century intervention that warily avoids normalizing standards and empties symbols of agreed-upon meaning. We may only be able to define hipsters because mass culture assiduously constructs them as a consumer demographic or the building blocks for urban engineering, because nearly nobody actually admits to being a hipster. While The Simpsons can parody hipsters with the confidence that we will recognize the stereotypes, the people who are cast in the category persistently attempt to escape stylistic and behavioral labeling. Romantic alienation to the mainstream, the allure of authentic selfhood, and perceived position on the margins animates many contemporary social collectives like hipsters, yet in the case of hipsters it is an utterly tactical politics and subjectivity whose materiality may signify nothing especially concrete. This may be a reflection of a post-segregation, digital consumer culture in which subjectivities are increasingly fluid, but we nevertheless remain products of historically deep-seated marginalization that fringe groups routinely evade at their own peril. Even in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, for instance, Mailer suggested Cold War hipsters attempted to “exist without roots,” a move that risked ignoring the historical depth of anti-Black marginalization. Archaeological analysis can very clearly “see” such marginalization, and with some reflective imagination we can more critically understand rich experiences of marginality and acknowledge genuine agency without lapsing into romantic pictures of authenticity and selfhood.

References

James Baldwin

1985 The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Anatole Broyard

1948 A Portrait of the Hipster. Partisan Review. http://karakorak.blogspot.com/2010/11/portrait-of-hipster-by-anatole-broyard.html

Cab Calloway

1938 A Hepster’s Dictionary. http://www.cabcalloway.com/jive_dictionary.htm

Richard Florida

2002 Bohemia and Economic Geography. Journal of Economic Geography 2:55-71.

2008 Who’s Your City?: How the Creative Economy Is Making Where You Live the Most Important Decision of Your Life. Basic Books, New York.

Brandon Gordon

2011 Physical Sympathy: Hip and Sentimentalism in James Baldwin’s Another Country

MFS Modern Fiction Studies 57(1):75-95.

Stephen Greenblatt

1980 Renaissance Self-Fashioning. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Mark Greif

2010a The Hipster in the Mirror. The New York Times 12 November. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/14/books/review/Greif-t.html?pagewanted=1&_r=0

2010b What was the Hipster? New York Magazine 24 October. http://nymag.com/news/features/69129/

Douglas Haddow

2008 Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization. Adbusters online.

Rob Horning

2009 The Death of the Hipster. PopMatters http://www.popmatters.com/pm/post/the-death-of-the-hipster-panel/

inCULTURE3

2012 Hipster Revolution, Style of Lifestyle? http://incultur3.com/hipster-revolution-style-or-lifestyle/

Fredric Jameson

1998 Postmodernism and Consumer Society. In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster, pp. 111-125. New Press, New York.

Ben Kessler

2012 Hipsters ‘R Us. In Perspectives by Incongruity, First of the Year: Volume 4, edited by Benj DeMott, pp.70-73. Transaction Press, New Burnswick, New Jersey.

Jake Kinzey

2010 The Sacred and the Profane: An Investigation of Hipsters. Zero Books, Alresford, UK.

Robert Lanham

2009 Look at this Fucking Hipster Basher. The Morning News online. http://www.themorningnews.org/article/look-at-this-fucking-hipster-basher

Richard Lacayo and Ginia Bellafante

2012 If Everyone Is Hip… …Is Anyone Hip? Time 144(6): 48.

Benjamin Lee

2010 Avant-Garde Poetry as Subcultural Practice: Mailer and Di Prima’s Hipsters.

New Literary History 41(4):775-794.

Andrea Levine

2003 The (Jewish) White Negro: Norman Mailer’s Racial Bodies. MELUS 28(2):59-81. (subscription access)

Richard Lloyd

2010 Neo-bohemia: art and commerce in the postindustrial city. 2nd Edition. Taylor and Francis, New York.

Christian Lorentzen

2007 Why the Hipster Must Die. Time Out New York online.

Norman Mailer

1957 The White Negro. Reprinted in Dissent, June 2007. http://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-white-negro-fall-1957

Gary T. Marx

1967 The White Negro and the Negro White. Phylon 28(2):168-177.

Ilie Mitaru

2009 Reconsidering the Hipster: An Acknowledgement of Potentiality. Adbusters online.

Ingrid Monson

1995 The Problem with White Hipness: Race, Gender, and Cultural Conceptions in Jazz Historical Discourse. Journal of the American Musicological Society 48(3):396-422. (subscription access)

Ned Polsky

1967 Hustlers, Beats, and Others. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago.

Steve Shoemaker

1991 Norman Mailer’s “White Negro”: Historical Myth or Mythical History? Twentieth Century Literature 37(3):343-360. (subscription access)

Douglas Taylor

2010 Three Lean Cats in a Hall of Mirrors: James Baldwin, Norman Mailer, and Eldridge Cleaver on Race and Masculinity. Texas Studies in Literature and Language 52(1):70-101

Ingrid M. Tolstad

2006 “Hey Hipster! You are a Hipster!”: An Examination into the Negotiation of Cool Identities. Master of Philosophy Thesis, Department of Social Sciences, University of Oslo.

Images

Berlin hipster image courtesy paulamarttila

Biking fashion image courtesy Lorena Cupcake

Hipster Dust image courtesy Hipster Dust

London Street art image courtesy Chris.Jeriko

Wicker Park cafe image courtesy Joel Mann

Wicker Park shop window image courtesy avrenim_acceber

Williamsburg real estate sign image courtesy EssG

Race and Suburban Homogeneity: The Flanner House Homes and Post-Urban African America

Long Island’s Levittown suburb established the models for material and social homogeneity commonly associated with postwar American suburbs (image MarkGregory007)

In the wake of World War II, suburbs sprang up on the outskirts of American cities, prefabricated and interchangeable homes that reflect postwar social, disciplinary, and material homogeneity. Boosted by Federal Housing Admininstration and veteran’s loans, banks provided loans for 10 million new homes between 1946 and 1953, and Americans set off for the suburbs to settle scores of standardized structures on urban outskirts.

When we imagine such suburbs, we invariably envision solidly middle-class families in the midst of homogeneous neighborhoods, a picture that rarely includes people of color. Access to America’s suburban utopia was denied to most African Americans: realtors, bankers, and urban planners crafted an ideologically distorted, racially restricted American Dream in the suburbs while they championed urban renewal projects that gutted the Black city. The Black experience of postwar suburbanization is a complicated presence on the contemporary landscape: the heritage of urban renewal is reflected in failed projects and abandoned cityscapes that many city governments now want to raze anew. However, an especially interesting dimension of that story is reflected in the Flanner House Homes neighborhood in Indianapolis, Indiana, a history that is now in danger of being forgotten if not displaced.

The suburban experience is routinely painted in homogeneous material and social terms for good reason. Perhaps no suburb better depicts that homogeneity than the original Levittown, the Long Island New York community where the Levitt Brothers built 17,447 homes by 1951. The FHA encouraged suburban planners to restrict the sale of suburban homes to Whites, calling Black residents “adverse influences,” and the Levitts embraced that advice. Bill Levitt rationalized the firm’s racial covenants restricting sales to Whites only with the argument that “As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But the plain fact is that most whites prefer not to live in mixed communities.” In 1960, Levittown’s 82,000 residents included not one African American, making it the single largest universally White community in America.

Levittown was an extreme example that concealed the one-million African Americans who became suburbanites in the 1940s and 1950s. For instance, African Americans had settled north of Detroit in the 1920s on vacant farmland in the Eight Mile-Wyoming area and built modest houses; such “self-built suburbs” constructed by their owners accounted for one-third of all pre-war homes, crafted over time from recycled materials or pre-cut Sears houses and without much planning by local governments. Yet as suburban developments sprang up on city outskirts apprehensive White suburbanites formed municipalities and established anti-Black residency covenants that restricted home sales to Whites (a pattern already tested in Indianapolis itself in the 1920s; compare such covenants in Kansas City and in Seattle).

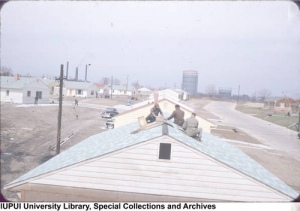

Men clearing yard spaces around their Flanner House homes (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

Flanner House builders complete the shell of one of a series of homes. No family could move in until all homes in a section were completed (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

The Flanner House Homes project was one distinctive response to the racist boundaries on post-war suburbs. Flanner House was founded in 1898 as a “settlement house” agency to assist Black residents arriving in 19th-century migrations and subsequently in the Great Migration. The city’s African-American population increased by almost 500% between 1860 and 1870, and in 1900 nearly 10% of the city’s population was African American. Boosted by Southern migration, that population more than doubled in the first two decades of the 20th century, increasing from 15,931 in 1900 to 34,678 in 1920.

In 1936 Tuskegee-trained Cleo Blackburn was hired as the Flanner House director, advocating a strong “self-help” mantra that would remain the Flanner House philosophy through the Depression, post-war decline, and the Civil Rights movement. In 1944 Blackburn directed the construction of a community cannery, health center, nursery, and gardens at its 16th Street headquarters. In 1945 Survey Graphic reported on the new center, indicating that Flanner House “has built a new settlement on the edge of what former U. S. Housing Administrator Nathan Straus called the worst Negro slum in America. It has been instrumental in constructing a new health center nearby. It is operating perhaps the largest community gardening and canning project by and for Negroes in the United States.”

A 1946 study of the neighborhood directed by Blackburn examined 454 Black households on the city’s near-Westside and agreed that the neighborhood was “one of the most unsightly, unsanitary, and deteriorated sectors in the entire city of Indianapolis,” and the homes “needed major repairs and few of them had adequate plumbing facilities.” Blackburn indicated that “the majority had given up hope for any possible improvement,” and he advised that it “is urgently recommended, that the clearance, planning, and redevelopment of this area under the Redevelopment Act of 1945 affords the only hope of correcting the conditions existing in the area. … Immediate steps should be taken by the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission to declare the area blighted and to acquire, clear, and redevelop it.”

Future Flanner House residents shingling their homes (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives)

Created in 1944, the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission was willing to raze the whole of the Black near-Westside, though it had relatively little plan for what to do with the uprooted residents. While most American cities accepted federal funding and built public housing for the scores of families displaced by urban renewal, Indianapolis persistently rebuffed federal funding for such construction under the guise of supporting local contractors. While the African-American near-Westside languished, 9000 new homes were built between 1940 and 1942 to support wartime workforces in Speedway and Warren Township, and 52,000 new homes were built in the city in the 1950’s, but nearly all were in neighborhoods inaccessible to African Americans.

Blackburn proposed tearing down a swath of homes and building “sweat equity” housing in which male head of households constructed their homes and the homes of their neighbors (women could not participate in home construction). The Redevelopment Commission purchased a 178-acre tract north of Crispus Attucks High School in November 1946, referred to as Project A, and after displacing the residents (none of whom were guaranteed acceptance into Flanner House Homes) they turned it over to Blackburn and Flanner House. Construction began in 1950 by a series of men whose families had been exhaustively reviewed by Flanner House, leaving Flanner House solidly peopled by middle-class African Americans.

Flanner House Homes was distinctive for its focus on African Americans in a moment when White urbanites were migrating to the outskirts of the city, but it was simultaneously novel spatially in its simulation of suburban space and its placement within the city. While similar homes were being built on Indianapolis’ rural outskirts, the Flanner House Homes sat just north of the city’s central “Mile Square.” Like many of the suburban homes they borrowed from stylistically, the houses are roughly 975-square foot spaces with standardized footprints and one of four basic street facings. There was nothing that especially distinguished the Flanner House Homes from any house in the White suburbs, and that may well have been Blackburn’s intention. These African-American homes were utterly typical suburban forms that reproduced the very middle-class values that were simultaneously staking a claim to the city’s suburbs. The city’s lone predominately Black suburb was the Grandview community, which was established on the city’s northwest side in the late-1950s. The stylish suburban ranchers and relatively standardized homes were derisively referred to in the local press as the “Golden Ghetto.”

A completed Flanner House homes street looked much like most suburban communities (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

There is nothing especially diasporan about the Flanner House home forms, a direct reflection of the African-American commitment to American middle-class values in particular and the American home ownership dream in particular. The homes might be cast as a reflection of Blackburn’s Tuskegee training, which was profoundly shaped by Booker T. Washington’s accomodationist philosophy, and Blackburn did indeed chart a circumspect and non-confrontational course in local race relations. However, this risks reducing all African-American heritage merely to essentialized diasporan forms and ignores the allure of suburban home ownership and agency in African-American experience.

Flanner House Homes was in some ways a tragic testament to the persistence of racism in Indianapolis. By 1964 the project had built just over 300 homes, and while the city persistently pointed to Flanner House Homes as a success story, it did not remotely address housing problems in Indianapolis and its racial segregation did nothing to address the racism that prevented people of color from moving into other Indianapolis neighborhoods. Realtors refused to show homes to Black households; banks were unwilling to extend loans to African Americans able to pay; and the near-absence of restricted income public housing provided African American few choices for housing. To make matters worse, the imminent arrival of Interstate-65 construction in 1965 would remove 4700 homes, of which roughly half were African American (and in view of Flanner House Homes). Richard Pierce’s compelling study Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970 concludes that when Indianapolis began to enforce laws against housing segregation in the late 1960’s, “Whites no longer needed racial covenants and neighborhood associations to block African American movement into white neighborhoods. The economic gap between whites and African Americans had grown sufficiently that economic realities provided the most effective barrier.”

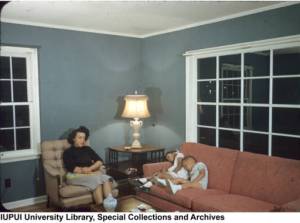

This woman and two children posed in a finished Flanner House home (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

Flanner Homes was named a National Register Historic District in 2003, but in 2013 Indiana Landmarks named Flanner House Homes and the neighboring Philip’s Temple one of Indiana’s Ten Most Endangered Historic Places. In 2012 the neighborhood first found itself under fire from the Indianapolis Public Schools, which owns Philip’s Temple but hopes to tear down the 1924 church to build a parking lot for Crispus Attucks High School.

The Flanner House homes were recently under fire from the retailer Meijer, who hoped to acquire and demolish 35 of the 181 Flanner House Homes just north of the neighborhood. Meijer removed their bid this week, and the neighborhoods’ resistance and Indiana Landmarks’ advocacy was critical. Nevertheless, the targeting of the neighborhood reflects that the homes’ apparently prosaic form masks their significance as a reflection of color line privileges.

For more details:

Listen to Amos Brown’s interview with residents and local preservations on Afternoons with Amos

Videos of original Flanner House residents and Flanner House can be found at the Flanner House youtube channel

References

Cleo W. Blackburn

1946 A Study of 454 Negro Households in the Redevelopment Area, Indianapolis, Indiana. Unpublished manuscript.

Carolyn M. Brady

1996 Indianapolis at the Time of the Great Migration, 1900-1920. Black History News and Notes 65.

Flanner House Study Committee

1939 The Indianapolis Study. Unpublished manuscript.

David M. P. Freund

2007 Colored Property : State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Kevin Fox Gotham

2000 Urban Space, Restrictive Covenants, and the Origins of Racial Residential Segregation in a US City, 1900-1950. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24(3):616-633.

Bernadette Hanlon

2009 Once the American Dream: Inner-Ring Suburbs of the Metropolitan United States. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Dianne Harris

2006 Seeing the Invisible: Reexamining Race and Vernacular Architecture. Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 13(2):96-105. (subscription access)

Dolores Hayden

2003 Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000. Knopf, New York.

Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission

1954 Annual Report of the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission for 1954. Unpublished manuscript.

Kenneth T. Jackson

1985 Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, New York.

Michael Jones-Correa

2000 The Origins and Diffusion of Racial Restrictive Covenants. Political Science Quarterly 115(4):541-568.

M. Ruth Little

1997 The Other Side of the Tracks: The Middle-Class Neighborhoods that Jim Crow Built in Early-Twentieth-Century North Carolina. In Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture VII, eds. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry, pp, 268-280. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Timothy Maher and Ain Haas

1987 Suburbanizing the City. Sociological Focus 20(4):281-294. (subscription access)

Richard Pierce

2005 Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Charles S. Preston

1946 Local Slum Clearance Plans Advanced by “New Resolution.” Indianapolis Recorder 9 November:1, 3.

Roger William Riis and Webb Waldron

1945 Fortunate City. Survey Graphic XXXTV(8)

Images

Flanner house Construction, yard construction, street scene, and women and children in living room images courtesy Flanner House (Indianapolis, Ind.) Records, 1936-1992, IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives

Levittown aerial view image image courtesy MarkGregory007

Sympathy for the Cannibal: Archaeology, Emotion, and Cannibalism

A reconstruction of the cannibalized teen girl referred to as “Jane” (image Studio EIS photo by Don Hurlbert, Smithsonian).

Today the Jamestown Rediscovery Project reported on the archaeology of a teen girl who was apparently butchered and consumed by fellow colonists in the winter of 1609-1610. Most of the instant press coverage revolves around the evidence that the body was butchered, with mandible cut marks and skull fragmentation reflecting a somewhat clumsy dismemberment of the body during a winter in which about 80% of the settlement’s residents died. Our collective fascination with this girl’s fate obliquely humanizes her even as we paint a sympathetic if uneasy picture of the fellow settlers who cannibalized her. The story of “Jane,” as Jamestown refers to her, paints the emotional incomprehensibility of human nature while simultaneously rationalizing the desperation that would have led these first settlers to consume one of their own number.

Cannibalism holds a powerful grip on human imagination for perfectly understandable reasons: to consume another human’s body is nearly always constructed as one of the most universal of all violations, driven only by absolutely total desperation, radical ritual, or simple tragic madness. Cannibals have been a staple of popular discourse for much of the colonial period, but the specter of the cannibal was routinely invoked as an ideological caricature of colonial peoples. William Arens’ 1979 study The Man-Eating Myth was a skeptical reaction against the ideological weight of cannibal narratives, with Arens rejecting nearly all accounts of cannibalism in virtually any time and place. Cannibalism certainly has been wielded to stigmatize various colonial “Others,” and contemporary uneasiness with cannibalism has led most scholars to be circumspect about the subject. Yet a wave of archaeologists have argued quite persuasively that the aversion to acknowledging cannibalism ignores quite significant evidence for it. Compelling examples reach back over 780,000 years ago at the Spanish site Gran Dolina; 100,000 year-old Neandertal remains at Moula-Guercy were clearly cannibalized; Walter Hough’s 1901 claim for Anasazi cannibalism is accepted by many contemporary scholars; the Colorado site Cowboy Wash dates to AD 1150-1175 and has been interpreted by one team as containing human fecal remains (coprolites) with identifiable human tissue remains alongside tools with human blood residues and bones suggesting cannibalism; and in winter 1846-1847 the well-known Donner party consumed members of their group when stranded in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Four chop marks on the top of the skull suggest other colonists were attempting to open the cranium (image Don Hurlbert, Smithsonian)

Armed with the mangled remains of this anonymous young woman and a historical case for such desperation, the Jamestown case weaves an exceptionally compelling human narrative. Archaeological narratives about cannibalism typically redeem the victims, humanizing them in the face of an unutterable end and providing an articulate narrative that rationalizes or tries to explain their death. That rationalization often finds a motivating force for cannibalizing another person, such as starvation, a move that obliquely redeems the cannibals as well as the victims. Jamestown ReDiscovery, for instance, refers to this girl’s remains as the earliest evidence of “survival cannibalism” in the colonial New World, eager to underscore that this cannibalism was driven by utter desperation. The team’s Scott Whitaker is one of the team scholars who march through a precise and persuasive forensic analysis of the skeletal evidence, focusing on Jane’s death as a scientifically analyzed process.

Such a rhetorical maneuver tends to evade the emotional incomprehensibility of consuming a human, which may in fact be our fundamental curiosity about such a fringe practice. The image of the young woman’s skull and awkward cut marks used to open her cranial vault push the limits of rationality for many us and may be a dimension of the girl’s story that archaeological rationality simply cannot resolve. However, archaeology can address the mechanics of dismemberment, and in the Jamestown case the skeleton is somewhat ineptly butchered and tends to reinforce the Jamestown assessment of this as the depths of desperation.

The story of this girl is part of the Smithsonian exhibit Written in Bone: Forensic Files of the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake, and her death makes a compelling archaeological narrative that may show how the discipline shares its findings. The team at Jamestown has honed their skills sharing such stories in a wave of fascinating YouTube videos and well-timed press releases in advance of the Smithsonian exhibition. The Jamestown press releases feature a facial reconstruction of the cannibalized girl, a method that has little genuine scholarly purpose but is an alluring vehicle for imagination in a museum gallery or a mass media article.

The line between circumspectly tapping into collective fascination and skirting the professional review process can be problematic. For instance, a 2000 American Antiquity paper by Kurt E. Dongoske, Debra L. Martin and T. J. Ferguson scolded a team at Cowboy Wash for publishing their findings in the popular Discover magazine under the title “American Cannibals” prior to having the data peer-reviewed. The team at Leicester University was criticized in some circles for likewise failing to present their findings on the Richard III excavation in peer-reviewed scholarship before orchestrating a internationally covered news conference. Jamestown’s press included such hyperbole as the Daily News‘ headline “Cannibal Colonists!: Remains at Jamestown show early American settlers ate each other” and Vanity Fair‘s snarky headline “Cannibalism at Jamestown is Most Interesting Thing to Happen at Colony since A.P. U.S. History Trip.”

There is perhaps good reason to sympathize with the settlers who consumed this dead young woman in a moment of “survival cannibalism.” Yet cannibalism resides at the boundaries of human experience, attracting our fascination even in the face of Jamestown’s picture of the colony’s true desperation. We cannot articulate that fascination in especially settled forms, so much of what this and other archaeologies of cannibalism do is provide a firm mirror into the vast breadth of human nature.

References

William Arens

1979 The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford University Press, New York.

Alban Defleur, Tim White, Patricia Valensi, Ludovic Slimak, and Évelyne Crégut-Bonnoure

1999 Neanderthal Cannibalism at, Ardèche, France. Science 286(5437):128-131.

Kelly J. Dixon, Shannon A. Novak, Gwen Robbins, Julie M. Schablitsky, G. Richard Scott and Guy L. Tasa

2010 “Men, Women, and Children Starving”: Archaeology of the Donner Family Camp. American Antiquity 75(3):627-656.

Kurt E. Dongoske, Debra L. Martin and T. J. Ferguson

2000 Critique of the Claim of Cannibalism at Cowboy Wash. American Antiquity 65(1):179-190.

Fernández-Jalvo, Yolanda, J. C. Díez, Isabel Cáceres, and Jordi Rosell

1999 Human cannibalism in the Early Pleistocene of Europe (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). Journal of Human Evolution 37(3-4):591-622.

Michael Harner

1977 The Ecological Basis for Aztec Sacrifice. American Ethnologist 4(1):117-135

Rachel B. Herrmann

2011 The “tragicall historie”: Cannibalism and Abundance in Colonial Jamestown. William and Mary Quarterly 3rd series 68(1):47-74.

J. S. Kidd

1988 Scholarly Excess and Journalistic Restraint in the Popular Treatment of Cannibalism. Social Studies of Science 18(4):749-754.

Patricia M. Lambert, Banks L. Leonard, Brian R. Billman, Richard A. Marlar, Margaret E. Newman and Karl J. Reinhard

2000 Response to Critique of the Claim of Cannibalism at Cowboy Wash. American Antiquity 65(2):397-406.

Richard A. Marlar, Banks L. Leonard, Brian R. Billman, Patricia M. Lambert, and Jennifer E. Marlar

2000 Biochemical evidence of cannibalism at a prehistoric Puebloan site in southwestern Colorado. Nature 407:74-78.

Timothy Taylor

2001 The Edible Dead. British Archaeology 59

Christy G. Turner, II and Jacqueline A. Turner

1992 The First Claim for Cannibalism in the Southwest: Walter Hough’s 1901 Discovery at Canyon Butte Ruin 3, Northeastern Arizona. American Antiquity 57(4):661-682.

Images

Facial reconstruction image from StudioEIS; Photo: Don Hurlbert, Smithsonian

Mandible with cuts image from Don Hurlbert, Smithsonian

Skull with cut marks image from Don Hurlbert, Smithsonian