Retreating to Exclusivity: Diversity and Place at Newfields

In 1964 New York designer Edward Durell Stone advised the Art of Association of Indianapolis to move the John Herron Museum of Art from its location at 16th and Pennsylvania Streets. The Association managed the Herron Museum, and they hired Stone and a team of consultants to assess the expansion or renovation of their aging 1906 facility. Yet when Stone told a Columbia Club audience that the museum should be moved to the western edges of the Butler University campus, he was greeted with a chorus of complaints that revolved around museum access, equity, and urban preservation. One person complained “Should it be some mysterious privilege of a few people to make the cultural blessings of the arts less accessible to all the people? A museum should be a busy place, centrally located near public transportation, near office buildings, near schools, near hotels and meeting and eating places near all the people in our community.” This was perhaps idealistic, but it actually was not a new sentiment: when the museum was dedicated in November 1906 a speaker argued that “an art museum should be an institution for the masses rather than for the classes.”

Now part of a complex renamed Newfields, the Museum is today struggling with equity and inclusion challenges that are certainly rooted in its institutional culture and common to many other art museums. Nevertheless, the institution’s 21st-century exclusivity also reflects the heritage of the landscape where the museum sits today. Today Newfields is located in what was an elite White area throughout the 20th century, not far from the location Edward Durell Stone advocated in 1964. Nevertheless, predominately working-class and middle-class African-American neighborhoods sit in walking distance of the museum campus. The contemporary experience of Newfields and the perception of its exclusivity is shaped by a broad range of factors, but it is firmly based in its own place-based heritage. A sober assessment of that landscape history should be an essential dimension of Newfields’ ambitions to be an inclusive museum.

Edward Durell Stone’s 1964 proposal came in the midst of rapid suburban growth, highway construction, and urban displacement, and those dramatic transformations in class, color, and place intersected with planning for the museum. Stone’s favored location was in the 4600 block of Michigan Road, which in 1964 was the home of executive Samuel M. Harrell (today it is a private residential compound). Today most observers would consider that location to be the heart of the city, but in 1964 one critic argued that “The suggested move of our art museum to the fringes of suburbia seems to be anachronism, completely out of context with the spirit of our times.” Another observer questioned moving the museum north of 30th or 38th Streets, arteries that still lingered as residential redlining boundaries between White neighborhoods to the north and Black neighborhoods to the south: “Must the city be divided with 30th or 38th the Mason-Dixon Line, below which the urban untouchables live? Our art museum must be for the people and easily accessible to all. It should be readily available to inspire those in need of contact and familiarity with art and beauty.”

Resistance to moving the museum was dismissed in November 1966, when the family of Josiah K. Lilly, Jr. donated the Oldfields mansion and grounds to the Art Association of Indianapolis for the former Herron museum. In November 1968 the Art Association announced it would soon begin building the new museum, which became the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 1969. The Indianapolis Star once again enthusiastically championed the museum as a community institution, declaring that “the new art center will not be exclusive territory for artists. Everyone will be encouraged to participate in museum activities. The art center will be truly a community affair.”

Despite such rhetoric, for much of its recent past the museum has struggled to turn the exceptional collections and surrounding grounds into an inclusive place (compare Ben Valentine’s 2013 assessment of the IMA’s shifting mission). After seven years of free general admission, in 2014 the museum instituted an admission fee “to maintain long-term financial stability,” and free admission to the grounds and bike access ended in 2015. In 2017 the museum rebranded itself as “Newfields,” referring to the whole complex of buildings and gardens on the museum grounds. Perhaps the most unsettling moment came in July 2020, when curator Kelli Morgan left the museum after labeling it a “toxic” working environment and questioning the institution’s commitment to inclusivity. Morgan wrote after her resignation that through “very deliberately racist and sexist practices of acquisition, deaccession, exhibition and art historical analysis, museums have decisively produced the very state of exclusion that publicly engaged art historians and curators like me are currently working hard to dismantle.” In February 2021 the museum came under renewed criticism when it posted a job notice seeking a candidate who would “attract a broader and more diverse audience while maintaining the Museum’s traditional, core, white art audience.” That clumsy admission of the museum’s racial homogeneity fueled a response by 85 staff members advocating assertive partnerships with diverse community constituencies and seeking the resignation of the museum’s director. The director desperately reaffirmed the museum’s “core commitment to inclusion,” but he resigned a few days later.

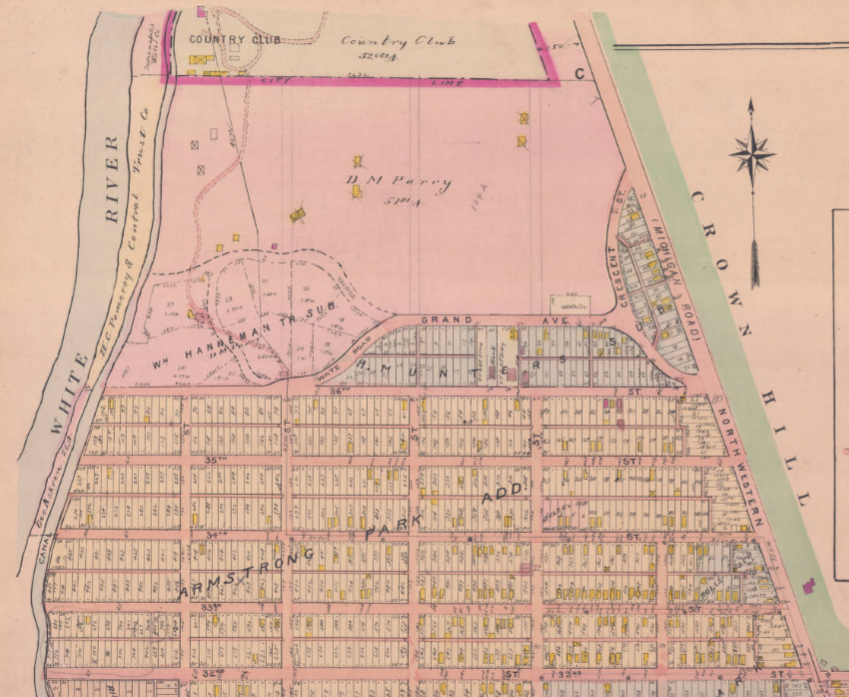

In the early 20th century the future museum grounds rapidly became an exceptionally affluent community at the margins of the city. Perhaps the first seed was planted at the end of the 19th century when the Indianapolis Country Club opened on the south side of Maple Road (now 38th Street). The club included the city’s most wealthy families, and when the first clubhouse was dedicated in November 1891, the Indianapolis Journal reported that there “was an unusual display of elegant diamonds, nearly every one’s costume being resplendent with these gems.” Indianapolis’ high White society gathered at the club for 20 years for golf, tennis, bowling, dancing, and fine food. The Country Club decided to move west of the city in 1912 (where it remains today), and Linnaes C. Boyd, Hugh McKennan Landon, Louis Cass Huesmann, and Arthur V. Brown purchased the roughly 48-acre property for $48,000. They initially planned to build “a high class residence district” (or a “preparatory school for boys”) on the tract that neighbored Hugh and Suzette Landon’s own home to the north. Today known as Oldfields, Landon’s home was built between 1911 and 1913 in an area that became known as Woodstock, and in 1932 the Landon home was purchased by Josiah K. Lilly, Jr.

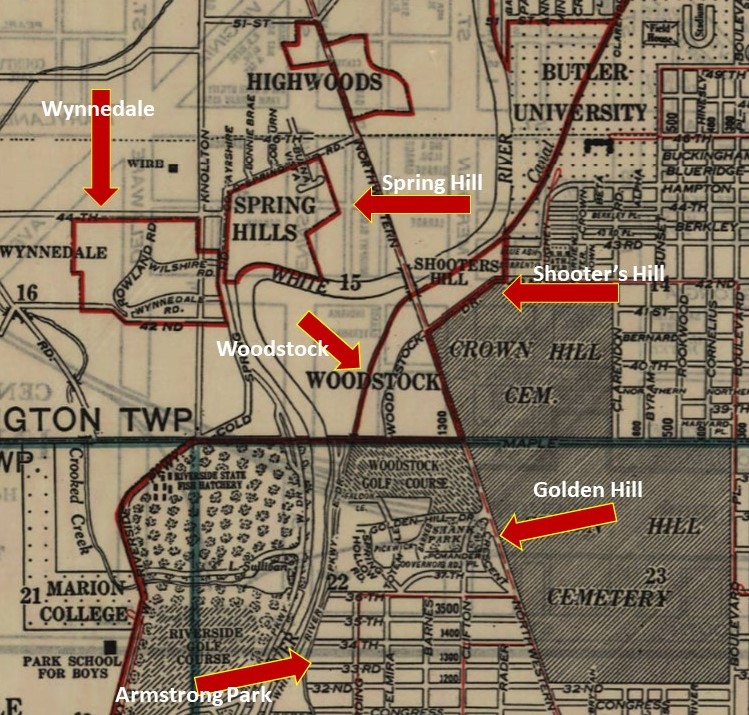

After the Indianapolis Country Club moved west, the property became the new Woodstock Club, which was incorporated in May 1915. Woodstock was incorporated as a town in November 1920, with just seven families living on 48 acres. Shooter’s Hill sat just east of Woodstock, and like Woodstock it was a very small and elite community. When Shooter’s Hill incorporated as a town in November 1925, it had just 14 residents, and in 1935 there were just three estates in the town. This pattern of affluent and small enclaves was repeated a series of times in the surrounding area: in July 1927, for instance, Crow’s Nest would file to become the 10th incorporated town in Indianapolis, a list that eventually included Spring Hills (incorporated in 1927 near Cold Spring and Michigan Roads) and Wynnedale (incorporated in March 1939, along Cold Spring Road on the west banks of the White River). Nearly all of these incorporated towns were composed of a handful of quite affluent residents: in 1940, for instance, the census recorded 19 people living in four households in Shooter’s Hill, including three people identified as servants, two as maids, and one as a houseman; a fourth household was a gardener, his wife, and two children renting one of the four residences, so there were essentially nine residents in three homes being served by 10 on-site laborers. The homes in Shooter’s Hill were purchased along with the complete 22-acre town by Christian Theological Seminary in 1963.

Oldfields was probably the most palatial home in the adjoining neighborhoods, and Golden Hill had the largest residential community. The Woodstock Club sat just north of Golden Hill, which had been a sparsely settled late-19th century resort spot. In October 1872, property began to be offered on a new subdivision marketed as “Clifton on the River,” but by June 1877 the area was being referred to as Golden Hill. In June 1879, for instance, a church picnic drew about 700 people to Golden Hill, and the Indianapolis News concluded that “No other place in this vicinity combines more of beauty and advantage than Golden Hill.” In April 1896 the Indianapolis Journal indicated that “Golden Hill has been one of the more popular picnic spots near here for many years,” reflecting that Golden Hill remained almost completely unsettled until the very end of the 19th century (the oldest home still standing in Golden Hill was built in about 1895).

In April 1892 John C. Shaffer purchased Golden Hill property adjoining the country club with plans to build a country estate, but in 1900 he sold his undeveloped tract to David M. Parry, who gradually purchased most of Golden Hill to create a family estate. Parry finished his Golden Hill home in 1904. Most of the streetscape and landscape planning in Golden Hill was done by Scottish immigrant George MacDougall, who landscaped Parry’s estate grounds beginning in 1908. After Parry’s death in 1915 his family hired MacDougall to plan the subdivision around Parry’s home; MacDougall also designed Stoughton Fletcher’s “Laurel Hall” estate, the streetscape for Woodstock in 1909, the Hugh McKennan Landon estate “Alverna” off Spring Mill Road, and the Nicholas and Marguerite Lilly Noyes home “Lane’s End” in Crow’s Nest.

In 1914 Parry and his family sold roughly 80 acres of Golden Hill to Arthur V. Brown, who planned to build “suburban homes,” and in September prospective residents were invited to visit the planned community. In April 1915 170 lots in the subdivision went on sale, and David Parry died just a month late. Lots sold relatively rapidly, with house construction occurring in the 1920’s and into the mid-1930’s by many of Indianapolis’ most noted architects. The Golden Hill Historic District now includes 54 residences.

The affluence of the neighborhood is suggested by the density of live-in service staff in the Golden Hill homes: in 1940, for instance, 15 live-in servants (and one nurse) were residents of Golden Hill in 13 different homes. Like all residential neighborhoods in the city, Golden Hill was racially segregated, though some of the elite estates were supported by live-in African-American service laborers. In 1910, for instance, John and Belle Kuykendall were living at 1306 West 36th Street in a home on David Parry’s estate, where John was working as a butler for Parry. The Kuykendalls moved out in about 1913, and only a handful of other Black service laborers would live in the neighborhood until after World War II. When the Home Owners Loan Corporation executed its residential security map for Indianapolis in 1937, Golden Hill was described as “Attractive location for property known as `small estates,’ yet not far from city center,” with no foreign-born or Black residents.

Golden Hill’s southern border is 36th Street, and south of 36th Street is now a neighborhood of predominately vernacular residences, most of which was originally known as the Armstrong Park Addition. Originally the home of the Armstrong family farm along Northwestern Street (i.e., Martin Luther King, Jr. Street), in May 1892 James Armstrong appealed to the Citizens Street Railway stockholders to improve streetcar access to his family’s newly opened park in north Indianapolis. Armstrong pled to the streetcar company that “With the help of the company I intend to make Armstrong Park the most attractive spot around Indianapolis. A large sum of money is to be spent in making it a beautiful place. Nature has made it the most desirable spot for a park around Indianapolis. … It is to be made a place where the best people of Indianapolis will go.” The Park invited urbanites to take the streetcar to Armstrong Park for picnicking, food, concerts, and boating, and church groups and even healers held meetings in the Park, but in June 1900 northside residents filed an injunction against public drunkenness in the park. In September investors tried to sell the whole tract as one property, but in October 1900 the Armstrong Park Land Company began to subdivide the tract into residential lots. The Indianapolis News reported in May 1901 that 550 of 689 lots had been sold, though most were purchased by real estate speculators and there was very little immediate construction. Five years later the News reported that 105 homes had been built in 1904, but about 40 families were living in tents on lots for which they had not completed payments. In 1908 the addition remained relatively sparsely settled, but by 1916 it had become relatively densely populated.

The neighborhood was quite densely populated in 1940, but there was not a single Black household in the neighborhood (though a Black family was settled at 3732 Northwestern Street). A few African-American residents had begun to settle homes immediately south of Armstrong Park, though, and the 1937 Home Owners Loan Corporation “redlining” map rated the neighborhood “definitely declining.” That “decline” was certainly based on the apparent “Encroachment of inharmonious groups (negro)” and the “Possibility of negro purchasers from territory south of 30th street.” The neighborhood began to include Black residents in the early 1950s, with sales notices for homes appearing in the Indianapolis Recorder by 1954.

The Armstrong Park neighborhood was overwhelmingly African American by the time the northwestside was targeted for construction of the northwest leg of Interstate-65. A plan for the route for I-65 through the near-Northside was proposed by engineers in January 1960, and surveying had begun by 1961. Residents of both Golden Hill and the African-American neighborhoods to their south were already contesting the highway plan in September 1959, when the highway department met with community. However, an engineer dismissed resistance and told the audience that “If the expressway is not built `Indianapolis will be a dying city. You can’t make a cake without breaking eggs … If it is so bad you can’t stand it, you’ll just have to move.’” The Indianapolis Recorder had already bitterly concluded in 1961 that “The battle is lost. Many Northside residents who, earlier last year, tried in vain to get Interstate 65 built anywhere except on the route proposed by the State Highway Department, are chiefly concerned now with the relocation and depreciation value of their homes.” In July 1963 the planned route from 38th Street south to 16th Street was expanded from four to six lanes, and in April 1964 Indianapolis Recorder article outlined the favored path for the interstate, crossing White River just south of Golden Hill at roughly 36th Street. In September 1966 a city planner acknowledged that the proposed Interstate-65 pathway bent around Golden Hill but cut through Armstrong Park, admitting “that Golden Hill is white and that these neighborhoods are Negro. The idea is prevalent in these neighborhoods that the route has more to do with race than with cost. … Another idea prevalent in these neighborhoods is that the projects are planned and scheduled to benefit the slum landlords” (who were profiting from re-housing displaced residents in very poorly maintained homes).

The most prominent voice against the highway came from Golden Hill resident Alan Clowes, who formed a group known as Livable Indianapolis for Everybody (LIFE) opposing the interstate. Clowes formed LIFE in December 1964 and lobbied against the interstate, calling the elevated roadway a “`Chinese wall of dirt’ which will do untold harm to this city’s future.” LIFE favored a northwest leg that ran along the western banks of the White River, cutting through Municipal Gardens and Belmont Parks, a route that would completely bypass Golden Hill and Armstrong Park. Clowes appealed to the Greater Indianapolis Progress Committee, a community advisory group that Mayor John Barton formed in December 1964. In June 1965, though, GIPC backed the proposed interstate plan, joining the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce and rejecting Clowes’ case for a different route or a below grade (a.k.a., “depressed”) interstate. By 1966 houses were beginning to be sold in the highway’s path through 31st through 36th Streets, a path that bisected Armstrong Park and the neighborhoods north of 30th Street; the interstate path would cut the formerly contiguous neighborhood into two sections separated by the elevated roadway.

In 1964 one critic of the plan to move the Herron Art Museum presciently predicted the transformation of conventional art museums beyond traditional gallery fare. He lamented that “An art museum on Michigan Road would degenerate into a place of weekend diversion rather than function as a place to see paintings.” Nearly the same argument was made in 2019 by Bill Watts, who complained that the renamed Newfields had shifted its focus from the arts to “curated outdoor experiences,” like putt-putt golf and holiday light shows. Newfields has perhaps insulated itself by restricting access to the grounds, imposing a steep admission fee, and focusing much of its programming on bourgeois suburbanites, and what may be most disappointing is that these shifts effectively retreat to the area’s 20th-century heritage of White elite exclusivity. The museum’s ability to fulfill its century-long commitment to serve a breadth of the city and embrace a diverse expressive culture is of course dependent on institutional transformations. Nevertheless, much of the story of the museum’s heritage is rooted in place-based exclusivity and requires Newfields develop a rigorous consciousness of their own landscape.

Sources

David Alan Ripple

1975 History of the Interstate System in Indiana: Volume 3, Part 1 – Chapter VI: Route History. Publication FHWA/IN/JHRP-75/28-1. Joint Highway Research Project, Indiana Department of Transportation and Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

Trent Spence

1996 Nicholas H. Noyes: An Historic Landscape Master Plan, Indianapolis, Indiana. Landscape Architecture Thesis, Ball State University.

Bradley D. Vogelsmeier

2013 Upper Class Enclave Identity: A Case Study of the Golden Hill Community. Undergraduate Honor’s Thesis, Butler University.

Images

Indianapolis Baist Atlas Plan # 33, 1908 Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection IUPUI University Library

Indianapolis Baist Atlas Plan # 33, 1916 Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection IUPUI University Library

Indianapolis George F. Cram Company, Inc., 1945. Historic Indiana Maps IUPUI University Library.

Oldfields, Indiana Landmarks H. Roll McLaughlin Collection, IUPUI University Library.

Parry Mansion in Golden Hill, from scrapbook created by librarian Alice K. Griffith, circa 1910-1920, Indianapolis Special Collections Room, Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library

Posted on April 19, 2021, in Uncategorized. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0