Blog Archives

Bourgeois Brew: The Landscapes of Craft Brewing

The landscape of contemporary bourgeois materiality is dotted with a legion of craft breweries, microbreweries, and brewpubs busily fermenting myriad new recipes targeting the upwardly mobile palate. The consumers of these modest breweries are increasingly well-versed in beer styles, the ingredients and chemistry of brewing, and the distinctions of regional styles and particular breweries. We are now in the midst of American Craft Beer Week, which is being celebrated May 13-19, and this celebration of handcrafted beers illuminates bourgeois consumption patterns, the idiosyncracies of bourgeois taste and style, and even the politics of craft beer consumption.

The bourgeois that have descended on craft breweries encompass a broad swath of social groups whose consumption revolves around material taste and stylistic distinction. This effort to craft distinction in material things is not especially uncommon, but bourgeois consumption tends to avoid shows of sheer affluence itself; that is, novelty, an appeal to progressive rationality (e.g., shopping green), and perceived individual stylistic distinction drive contemporary bourgeois consumption. This picture of bourgeois consumption stands idealistically opposed in the bourgeois imagination to the homogeneity, function, and thrift that fuel mass consumption, and the tendency to avoid shows of wealth stands opposed to the pretentious material affluence associated with the uber-wealthy (compare the counter-cultural capitalists David Brooks calls “bourgeois bohemians.”) To be bourgeois is to possess refined tastes even in the absence of genuine affluence, so it is not purely a show of material wealth as much as it is both material and social capital shaping consumption. Consequently, this definition of the bourgeois could reasonably include upwardly mobile yuppies, hipsters, indebted university students, and older educated urbanites.

Artisan foods from cheeses to chocolates have secured a market foothold by appealing to the educated palate, and beer appears to have been especially successful securing a place in bourgeois and aspiring bourgeois foodways. In March, 2013 the US had 2,360 craft breweries (which includes 1124 brewpubs, 1139 microbreweries, and 97 regional craft breweries). The central challenge for these small breweries is simply to dent consumer consciousness in a marketplace crowded with designer porters, and breweries wield a variety of symbolic mechanisms to secure consumers’ cultivated palettes. Bourgeois taste cherishes novelty and the symbolic capital derived from demonstrating mastery of beer knowledge and being an early adopter of a particular brew. Much of the microbrew rhetoric points to the cultivation of such discerning palettes, a mechanism that fashions bourgeois drinking as educated and individual. The Brewers Association, for instance, suggests that the “hallmark of craft beer and craft brewers is innovation. Craft brewers interpret historic styles with unique twists and develop new styles that have no precedent.” They stress that “Craft beer is generally made with traditional ingredients like malted barley; interesting and sometimes non-traditional ingredients are often added for distinctiveness.”

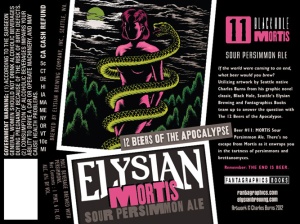

Some brewers paint themselves as fringe firms, hoping to evoke some of the imagined outsider status consumer subcultures routinely cherish. The Lagunitas Brewing Company’s offerings, for instance, include “Censored” ale: “Originally called the Kronik, this beer was censored by the federal label-approving agency … they claimed the word had some sort of Marijuana reference. We slapped a `Censored’ sticker on it as a joke and they accepted it.” Lagunitas crafts a distinctively independent California personality, indicating their mission has been “driven unseen by an urge to communicate with people, to find our diasporidic [sic] tribe, and to connect with other souls adrift on a culture that had lost its center and spun its inhabitants to the four winds to wander lost and bereft with a longing to re-enter the light. Beer, we have learned, has always been a good lubricant for social intercourse!” Other breweries hope to secure out attention with a cleverly named brew: Indiana’s 3Floyd’s Brewery makes a “gushy undead” pale ale it calls “Zombie Dust”; California’s Buffalo Bills Brewery offers up “Alimony Ale”; and Middle Ages Brewing Company makes a barleywine it calls “Druid Fluid.”

Chicago’s Wicker Park touts itself as having “the most complete set of beer oases in Chicago.” The neighborhood celebrates the presence of two “cicerones” amongst these craft bars (a beer consumers’ version of a sommelier), both of whom have been certified to have “the knowledge and skills to guide those interested in beer culture, including its historic and artistic aspects.” The cicerone certification identifies “a person with demonstrated expertise in beer who can guide consumers to enjoyable and high-quality experiences with great beer.” One of these cicerones lords over Bangers and Lace, a bar and restaurant “with the feel of a Midwestern lodge” that serves up bangers (i.e., sausages) and lace (i.e., the “Brussels lace” foam that clings to a beer mug). The nearby Moonshine brewpub likewise touts their brewmaster. Moonshine accents his “outsider” status by dubbing him a “renegade brewer” and underscores his brewing skills by noting that he “studied at North America’s oldest brewer’s academy, Siebel Institute, as well as the world-renowned Doemens brewer’s academy in Germany.”

Boutique beers are often difficult to find and more expensive than macrobrews, but craft beer is in many consumers’ minds a more economical option than options such as wine. A drinker at the Lagunitas Brewing Company told AdWeek that “for five or six dollars, we’d rather drink really good beer than mediocre wine.” This fashions craft beer more as a reflection of an educated palette than affluence alone. Simultaneously, craft beer is fashioned in somewhat contradictory forms as part of an “every-man’s” tradition of drink, which clumsily situates craft brews in a working-class heritage. This runs somewhat counter to craft breweries’ tendency to frame consumption as a reflection of cultivated individual taste; where working class drinking fosters homogeneity, bourgeois consumption celebrates novelty and individual discernment distinguishing the consumer. This contradiction awkwardly negotiates bourgeois consumers’ own acknowledgement of their social and material homogeneity; even as they drink a novel IPA and embrace a distinctive sense of style, they share dress, taste and values.

Among the most distinctive of craft beer names is Clown Shoes Beer’s Tramp Stamp pale ale (image Clown Shoes Beer).

Craft brewers invoke “community” in a variety of somewhat ambiguous ways that evade the distinct class of consumers who patronize such breweries. A January, 2013 survey found that “fully half of craft beer devotees are interested in locally made beer, while 25 percent are interested in purchasing craft beer only where it’s brewed.” Indianapolis’ Triton Brewing Company celebrates its values of being “a creative outlet in the form of a traditional, community-based production brewery located in the heartland of Indiana. The shareholders, employees, and libations of Triton Brewing Company embody exemplary strength of character, resolute integrity, and consistent quality in all their forms.” The Brewers’ Association likewise celebrates their local connections, indicating that “Craft brewers have distinctive, individualistic approaches to connecting with their customers.” The Lagunitas Brewing Company’s founder indicates that “What will help us in the long run is that essentially we are not in the same business as the multinational brewers. We are selling community, and they are selling liquid.”

Many craft breweries root themselves in a place through historical reference. San Francisco’s 21st Amendment Brewery cleverly links their business to the city’s early 20th century heritage, when “there were about 40 breweries operating just within the city limits.” Those breweries were “the local gathering places. Places to exchange ideas, debate politics and philosophy. Places for families to come together on weekends. Places that provided something unique—hand crafted beer that was different at every brewery and that defined the taste of a neighborhood. In 1920, Prohibition wiped out this culture and put the `local’ out of business. … But with the passage of the 21st Amendment, repealing Prohibition, we, as a society, were able to begin the slow climb back to reclaiming the essence of the neighborhood gathering place. At the 21st Amendment, they celebrate the culture of the great breweries of old, making unique, hand crafted beers, great food, and providing a comfortable, welcoming atmosphere that invites conversation, interaction and a sense of community.” Like 21st Amendment, FEW Spirits is an Evanston, Illinois distillery that plays on prohibition history by taking takes its name from Evansville temperance reformer and suffragist Francis Elizabeth Willard.

Craft breweries are a common feature of the contemporary upwardly mobile urban landscape. For instance, Chicago once had more than 50 Schlitz “tied houses,” pubs that sold beers from just one brewery, and many now house new businesses in urban neighborhoods. Increasingly more breweries are being turned into homes, commonly marketed as “brewery lofts.” Los Angeles’ Brewery Arts Complex, for instance, is a former Pabst Blue Ribbon plant that was re-tooled into homes and studio spaces that are rented only to artists. The E&B Brewery Lofts in Detroit are residential lofts in the former Eckhardt and Becker Brewery, which operated in the building from 1891 to 1969 and now also houses the Red Bull House of Art. The Gund Brewery Lofts in LaCrosse, Wisconsin break from the model of brewery lofts as artists’ havens, instead offering low-income housing.

Batch 19 plays off Prohibition heritage and drinking as a forbidden pastime, but the beer is made by macrobrewery Coors.

The craft breweries’ modest share of the American marketplace belies the appeals of craft beers that potentially reach well beyond even a broadly defined bourgeois. This week the Das Ale Haus blog reported on the faux craft label beers produced by macrobreweries intent on securing an ever-expanding slice of America’s alcoholic palette. For instance, labels like Goose Island and Blue Moon borrow from much of the symbolism and advertising rhetoric of craft breweries but are owned by Anheuser Busch and Molson-Coors, respectively. Where craft beers may have mastered a certain narrative that macrobrewers are eager to capture, macrobreweries have the profound advantage of marketing and distribution networks and the capacity to sell their products at low prices. Yet the macrobreweries face declining domestic and imported beer sales while craft beer profits steadily increase, and craft beers have secured much of their success from young consumers: A 2013 study found that consumers aged 25-34 are craft beer’s primary market, with 50% of the demographic consuming craft beer, and 43% of millennial and Gen X consumers prefer the taste of craft beer to domestic. The same study concluded that the craft beer market of $12 million in 2012 will reach $18 billion by 2017, international markets such as Australia reflect similar trends.

Images

Clown Shoes Tramp Stamp label image courtesy Clown Shoes Beer

Durham Craft Beer image courtesy lpolinski

Elysian Brewing label image courtesy firstwefeast.com

Schlitz tied house image courtesy kendoman26

Shipyard Brewing Company image courtesy brentdanley