Blog Archives

The Faces of Otzi: Imagining the Dead

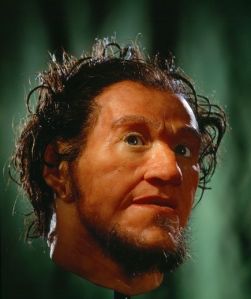

The newest Otzi reconstruction in the South Tyrol Museum (image Kennis © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Foto Ochsenreiter)

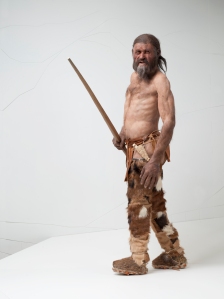

Few artifacts are more compelling than the twisted body of Otzi, the 5300-year-old man removed from Alpine snow in 1991. Archaeologically, Otzi is a unique snapshot of a life and a distinct moment, his assemblage revealing Copper Age materiality, his body telling the story of life in the Alps over five millennia ago, and his story illuminating a violent moment and a fascinating death story in which Otzi apparently met his end in a mountaintop murder. Otzi has been the subject of over 20 years of scientific investigation, archaeological discussion, and popular curiosity, and he is now celebrated in liqueur, snow globes, and assorted trinkets as well as an Otzi Village outdoor museum and a museum in which Otzi’s preserved body stares back at the curious. He has also been reconstructed continually for over 20 years, and that process underscores that facial and bodily reconstruction may invoke scientific accuracy but it is perhaps more about imagining human familiarities across the breadth of time.

Otzi’s five thousand years in the ice preserved him exceptionally well. Nevertheless, much like many other archaeologically recovered human forms such as unwrapped mummies, bog bodies, or skeletal remains, Otzi’s discolored and misshapen remains bear the unmistakable traces of human form—limbs, facial aesthetics, fingernails, toes—even as his distorted body aesthetically distances him from the present. Otzi is somewhat uncomfortably like us even as his millennia-old body betrays its distance from us in the present.

One way we can imagine Otzi’s story is through the series of facial and bodily reconstructions done over more than 20 years. Such reconstructions have become a staple of popular archaeological narratives: the unveiling of an anonymous teen cannibalized at Jamestown, Virginia featured a facial reconstruction; Richard III’s remains were shared in Leicester in February alongside a forensic approximation; the purported face of Alexander the Great’s father Philip II has been reconstructed with a disfiguring eye injury; and scans of French King Henri IV’s skull—removed from his grave in 1793 before being identified two years ago–were used to produce a facial reconstruction of Henri, who died in 1610.

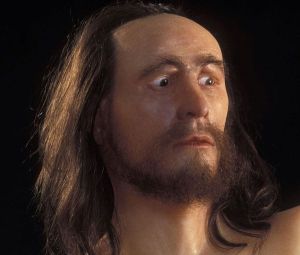

Otzi has been interpreted with a surprisingly broad range of faces. A rich scholarly literature examines the specific methods used to reconstruct facial forms with skeletal remains, but most of it revolves around “accuracy” in some objective physical form. It is not clear that the reconstructions of Otzi or any of these other subjects need to stake a claim to absolute accuracy, though; instead, they illuminate the distance between past and present, particularly the archaeological artifact that displays its historical distance. On the one hand, the Otzi reconstructions over 20 years cast the same body in a vast range of forms and illuminate the methodological complications of accurate reconstructions; on the other hand, though, the many faces of Otzi may be more important as efforts to evoke and imagine an inaccessible human experience and fashion a subjectivity for this anonymous corpse.

Facial reconstructions are artifacts in their own right, distinctively neither archaeological things nor pure contemporary constructions. On some level reconstructions are simply emotionally evocative mechanisms that fashion a corpse or skeleton into some bodily familiarity. Facial reconstructions have no particularly concrete interpretive purpose except to evoke human familiarity. For instance, when the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology unveiled its new Otzi reconstruction in 2011, the museum’s director indicated that “This accurate yet sensitive representation of Ötzi will fascinate and stir people around the world. It gives our history a face, in the truest sense of the word.” Germany’s National Geographic editor celebrated the newly imagined Otzi, proclaiming that “now we can finally look him in the eyes and recognise, to our amazement, that he is really one of us!”

On another level beneath the somewhat shallow embrace of our common humanity, a reconstruction gives an artifact—a partial skeleton, a mummified body, a corporeal form otherwise stripped of its subjectivity–a human identity. In his analysis of the “personification” of Otzi, John Robb has argued that this is “our act of supplying what we feel to be the essential dimensions of any body which are missing here.” Otzi is an archaeological artifact who comes to us as an anonymous dead person whose personhood and story are animated by archaeological narrative and a facial or bodily reconstruction. Otzi’s skin and soft tissue make him an especially powerful symbol of such personhood, having recognizable material traces of humanity and rich archaeological evidence to weave a fascinating life story. The nameless Jamestown teen, in contrast, is a fragmented skeleton recovered outside a discrete burial context who could easily be depersonalized, but she has been wound into a compelling narrative about the boundaries of human desperation.

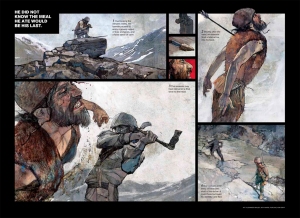

In 2008 a National Geographic editor suggested that such reconstructions “make some people, particularly scientists, squirm. Why? Because they are primarily art.” National Geographic itself featured a graphic novel style depiction of Otzi’s death drawn by Bulgarian comic artist Alex Maleev, but it weaves a story reasonably true to the archaeological analysis. In contrast, the reconstructions of Otzi are compelled to wield some measure of methodological and interpretive flexibility.

This National Geographic depiction of Otzi’s last moments was drawn by comic book artist Alex Maleev.

Archaeologists are probably not especially apprehensive of art as much as art weaves emotional, idiosyncratic, and fragmentary narratives that aesthetically and textually expand conventional archaeological interpretation. Facial and bodily reconstructions probably add little or nothing to our archaeological analysis, but they lend a powerful emotional dimension to the archaeological interpretation of a human body and life. Such narratives and facial reconstructions risk lapsing into ideologically distorted notions of individuality and focusing on a single life in isolation from a broader social and historical context. Nevertheless, reconstructions provide an interesting artifact that illuminates how archaeology breathes humanity into a corporeal artifact like Otzi, the Jamestown victim, and the scores of skeletal humans recovered by countless archaeologists.

References

Peter Acs, Thomas Wilhalm, and Klaus Oeggl

2005 Remains of grasses found with the Neolithic Iceman “Ötzi.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 14(3):198-206. (subscription access)

Roberta Ballestriero

2010 Anatomical models and wax Venuses: art masterpieces or scientific craft works? Journal of Anatomy 216(2):223-234.

Juan Gabriel Bridaa, Marta Meleddub, and Manuela Pulinac

2012 Understanding Urban Tourism Attractiveness The Case of the Archaeological Ötzi Museum in Bolzano. Journal of Travel Research 51(6):730-741. (subscription access)

Andy Coghlan

2012 Ötzi the ice mummy’s secrets found in DNA. New Scientist 213(2854):10. (subscription access)

Walter F. Kean, Shannon Tocchio, Mary Kean, and K. D. Rainsford

2013 The musculoskeletal abnormalities of the Similaun Iceman (“ÖTZI”): clues to chronic pain and possible treatments. Inflammopharmacology 21(1):11-20. (subscription access)

Andreas G. Nerlich, Beatrice Bachmeier, Albert Zink, Stefan Thalhammer, and Eduard Egarter-Vigl

2003 Ötzi had a wound on his right hand. The Lancet 362(9380):334.

John Prag and Richard Neave

1997 Making Faces: Using Forensic and Archaeological Evidence. Texas A & M University Press, Austin.

Alois G. Puntener and Serge Moss

2010 Otzi, the iceman and his leather clothes. CHIMIA International Journal for Chemistry 64(5):315-320. (subscription access)

John Robb

2009 Towards a Critical Otziography: Inventing Prehistoric Bodies. In Social Bodies, edited by Helen Lambert and Maryon McDonald, pp 100-. Berghan Books, New York.

C.N. Stephan

2005 Facial approximation: a review of the current state of play for archaeologists. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 15(4):298-302. (subscription access)

Laura Verzé

2009 History of facial reconstruction. Acta Biomed 80(1):5-12.

Caroline Wilkinson

2004 Forensic Facial Reconstruction. Cambridge University Press, New York.

2010 Facial reconstruction–anatomical art or artistic anatomy? Journal of Anatomy 216(2):235-250.

Graphics

Otzi South Tyrol image Kennis © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Foto Ochsenreiter

Otzi comic image from National Infographic

Otzi Museum image South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology