Consuming Marginality: An Archaeology of Hipster Materiality

This weekend I am in Chicago at the Theoretical Archaeology Group conference and delivering this paper examining the relationship between identity in post-segregation society and the legions of contemporary groups that see themselves as marginal. This revisits some of the issues I raised in my December 2012 post on hipsters but focuses on the relationship between, on the one hand, the erosion of ideological frameworks for identity—Blackness in particular, but also patriarchy, middle class, and urbanity—and, on the other hand, contemporary consumer collectives like hipsters that willingly embrace “marginality.”

In 1957, Norman Mailer lamented the hipster, the White youth who had become alienated to a society that had delivered depression, global war, the threat of nuclear apocalypse, and stultifying post-war homogeneity. Mailer argued that for these disillusioned Cold War hipsters, “the only life-giving answer is to … divorce oneself from society, to exist without roots.” Mailer dubbed the hipster “the White Negro,” because these disaffected White youth ostensibly divorced themselves from bourgeois discipline and appropriated African-American dress, music, and style, finding an “authentic” emotional experience in African American life. Mailer suggested that “in this wedding of the white and the black it was the Negro who brought the cultural dowry. Any Negro who wishes to live must live with danger from his first day, and no experience can ever be casual to him.” Mailer suggested that Whites were fascinated by Blacks’ unfettered emotion in the face of totalizing marginalization and felt similarly oppressed by a “slow death by conformity.”

From the vantage point of early 21st-century post-segregation consumer culture, the rejuvenated specter of the hipster again evokes marginalization and the quest for authenticity. Popular observers commonly reduce contemporary hipsters to a hollow caricature or see nothing especially consequential in yet another fringe social collective, but hipsters reflect the collapse of essentialized identities once anchored by the likes of racial subjectivity. In the vacuum created by the assault on race, masculinity, and the bourgeois, the hipster is a symptom of a widespread desperation to secure renewed authenticity once provided by those very ideologies. During the Cold War Mailer suggested that hipsters divined such authenticity in African American life, which posed a dramatic break from White bourgeois materialism and post-war homogeneity. Sociologist Ned Polsky was among the observers who argued that such a break simply thieved diasporan style and culture, arguing that “in the world of the hipster the Negro remains essentially what Ralph Ellison called him–an invisible man.” Yet hipsters did not simply appropriate African diasporan culture; rather, hipster culture crystallized Whites’ perpetual romantic fascination with the unfeigned authenticity of Black emotional experience and confirmed White envy of Black survival in the face of totalizing marginalization.

In the midst of a post-segregation society more than a half-century later, contemporary hipsters stake out a position that remains rooted in marginality, but they appear to have been joined by the breadth of American society in their claim to peripheralization. Cold War and contemporary hipsters share a common subcultural impulse to distinguish themselves through material style, but seemingly the full breadth of contemporary society has carved out its own stylistic niches. The erosion of racial, patriarchal, and bourgeois subjectivity has produced a very distinctive 21st-century hipster alongside a host of other social subjects—doomsday preppers, the Tea Party, the Occupy movement–seeking some substantial foundation for selfhood that expresses their experiences and ambitions. “Seeing” marginality is no longer especially challenging; indeed, archaeologies that aspire to “see” distinctive marginality risk reproducing an essentialism that Cold War White hipsters and Norman Mailer imposed when they romanticized Black emotional authenticity and racial experience. James Baldwin tempered such romanticism over the hipster’s creative construction of self when he argued that “a Negro man … had to make oneself up as one went along … in the not-at-all metaphorical teeth of the world’s determination to destroy you.” The challenge is to “see” structural processes of marginalization in everyday material life without lapsing into a romanticized picture of myriad socially marginal groups creatively crafting their authenticity.

Like many fringe groups before them, contemporary subcultures feel somehow alienated to an ambiguous “mainstream.” That mainstream may always have been more ideological than objective reality, and the perceived descent into universal marginality is at best contrived. However, the mainstream was long anchored by ideological bedrocks like Black difference that have now been unraveled by 21st-century hybridity, even as we remain persistently attached to material and cultural distinction; the hipster is simply one collective amongst us aspiring to craft a position in a society that seems hostile to our distinctive ambitions. Once a contested power relationship that produced distinction through concrete structural inequalities, marginality is now celebrated for its animation of consumer creativity and self-identification.

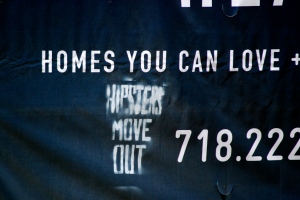

Precisely what defines a hipster today is ambiguous, and it is as much a slur, a transparent ideological notion, a youth culture demographic, and a marketing category as it is a coherent social subjectivity. The contemporary stereotype of hipsters revolves around materiality: for instance, hipsters wear vintage clothes from thrift shops or retro style from chains like Urban Outfitters that manufacture patina, and they accent such clothes with Chuck Taylors and Wayfarers; they embrace “low-brow” materiality like drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon or smoking European cigarettes to disguise their class standing; and like all subcultures they are fervent music consumers. Richard Florida suggests that these youth live in “hipster havens” like Wicker Park and Williamsburg, which, in his words, “attract a relatively affluent crowd—that doesn’t want to appear too affluent.” Yet these characterizations are in many ways simply a social caricature if not a marketing category that through popular repetition aspires to assume its own authenticity (for a compelling study of Wicker Park, see Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City)

A Wicker Park shop window appeals to the hip who live in the Chicago neighborhood (image avrenim_acceber).

It would be easy to dismiss hipster discourses as superficial fashion critiques, but the anxieties over present-day hipsters betray more deep-seated apprehensions over the shallowness of contemporary consumer politics. Christy Wampole’s New York Times piece “How to Live without Irony” laments the superficial materiality of the hipster, who “tries to negotiate the age-old problem of individuality, not with concepts, but with material things.” This critique romanticizes a counter-culture steeped in intellectual creativity, strategic politics, and some sort of common politicizing experience, but this idealized activism is an awkward fit to 21st-century society: the “mainstream” is an ambiguous if not ideological target; and the guise of authentic, shared oppression fueling strategic politics idealizes collective resistance. Wampole and many other observers remain romantically attached to a notion of “pure, unfettered subjectivity” in which human agency places us outside relations of power and marginalization, a position from which critical political activism is launched against marginalizing mainstreams.

Hipster materiality mines the detritus of dead aesthetics to craft contemporary distinction, but many observers dismiss such consumption as pallid mimicry of historical styles. In 2008, for instance, Adbusters’ Douglas Haddow theatrically lamented, “An artificial appropriation of different styles from different eras, the hipster represents the end of Western civilization – a culture lost in the superficiality of its past and unable to create any new meaning.” Under the hateful banner “the Hipster Must Die,” Christian Lorentzen similarly complained that “hipsterism fetishizes the authentic and regurgitates it with a winking inauthenticity.” Yet hipsters’ tactical fabrication of style from the shreds of popular culture may be what we all have done across the breadth of consumer society: that is, we all fancy ourselves creatively reconfiguring the commercial symbolism pinned on brand goods, store devotion, seasonal styles, and popular culture instead of inheriting our sense of self from art, faith, and Culture. The former are dismissed as inauthentic and meaningless, but hipsters may be mining those historical symbols consciously recognizing they are hollow; that is, it may well be that the appropriation of “dead,” once-authentic styles is in fact intended to signify nothing concrete beyond the idiosyncratic display of material style.

Such styles emptied of their historicity may be what Fredric Jameson referred to as the “perpetual present” in which “all that is left is to imitate dead styles.” Individualized creativity lies at the heart of contemporary hipster materiality, yet it does risk coming in the absence of especially concrete collective consciousness. Where the Cold War hipster fetishized the electric vitality of unfiltered Black emotional experience, the contemporary hipster may be seeking the fantasy of unfettered creative expression in the face of mass cultural conformity. Such individual creativity is then subject to the withering and unpredictable logic of hipster taste, which is geared to idiosyncratic aesthetic novelty and emotive instinct more than rationality, historical reference, or a concrete notion of stylistic politics.

Despite the absence of concrete hipster standards, the hipster risks serving consumer capitalism as a stylistic arbiter for mass culture. Indeed, marginal collectives from Metal fans to Whovians to hippies have become the foot soldiers for mass marketers, divining novelty from the subcultural fringes and delivering it to marketers. Hipsters, for instance, fixate on retro style and patina that pervades the contemporary marketplace. Rather than outsiders, hipsters instead loom as marketing mercenaries in a world of heterogeneous styles in which resistance, deviance, and rebellion are handed over to mass culture and reduced to consumable fashions.

Observers critical of de-historicized hipster retro persistently accuse hipsters of in-authenticity. Douglas Haddow, for instance, laments that hipsters are “a lost generation, desperately clinging to anything that feels real, but too afraid to become it ourselves. We are a defeated generation, resigned to the hypocrisy of those before us, who once sang songs of rebellion and now sell them back to us. … The hipster represents the end of Western civilization – a culture so detached and disconnected that it has stopped giving birth to anything new.” In this overwrought moralism, the hipster is the symptomatic tip of a mass cultural iceberg that has become stalely self-referential, utterly insincere in its politics and emotions, and alienated to a public life.

Yet perhaps hipsters are not imitating marginality as much as they are willfully inhabiting it and claiming the crowded fringe as an empowering social position. This is in some ways like the break their peers hoped to make from Cold War homogeneity when they embraced Black marginality and feeling. However, the fantasy of “being Black” was at best an awkward fetishization; while it took aim on race by recognizing marginalization as a social process and not an essential identity, only Whites enjoyed the privilege of performing Blackness across the color line.

There is a lesson here for archaeologies of marginality that presses us to push beyond essentialization even as we acknowledge the power of such categories, the allure of material distinction, and the tension of “mainstream” social mores. Archaeology illuminates marginalization processes, not simply marginal peoples: contemporary cityscapes, for instance, are the legacy of racist urban renewal programs with lasting effects touching dispossessed African Americans as well as transplanted hipsters. Rather than articulate the challenge as “seeing” marginal peoples in these past and present landscapes, perhaps the question is instead how to problematize a romantic notion of alienation that allows us to imagine ourselves apart from a social mainstream. Alienation allows us to fantasize an authentic self who can somehow be made “visible” in the midst of totalizing marginality, which risks evading the social and ideological construction of selfhood: Mailer’s hipsters, for instance, remained White despite their earnest desire to repudiate “every social restraint and category.”

In this sense, contemporary hipsters offer a particularly interesting 21st-century intervention that warily avoids normalizing standards and empties symbols of agreed-upon meaning. We may only be able to define hipsters because mass culture assiduously constructs them as a consumer demographic or the building blocks for urban engineering, because nearly nobody actually admits to being a hipster. While The Simpsons can parody hipsters with the confidence that we will recognize the stereotypes, the people who are cast in the category persistently attempt to escape stylistic and behavioral labeling. Romantic alienation to the mainstream, the allure of authentic selfhood, and perceived position on the margins animates many contemporary social collectives like hipsters, yet in the case of hipsters it is an utterly tactical politics and subjectivity whose materiality may signify nothing especially concrete. This may be a reflection of a post-segregation, digital consumer culture in which subjectivities are increasingly fluid, but we nevertheless remain products of historically deep-seated marginalization that fringe groups routinely evade at their own peril. Even in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, for instance, Mailer suggested Cold War hipsters attempted to “exist without roots,” a move that risked ignoring the historical depth of anti-Black marginalization. Archaeological analysis can very clearly “see” such marginalization, and with some reflective imagination we can more critically understand rich experiences of marginality and acknowledge genuine agency without lapsing into romantic pictures of authenticity and selfhood.

References

James Baldwin

1985 The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Anatole Broyard

1948 A Portrait of the Hipster. Partisan Review. http://karakorak.blogspot.com/2010/11/portrait-of-hipster-by-anatole-broyard.html

Cab Calloway

1938 A Hepster’s Dictionary. http://www.cabcalloway.com/jive_dictionary.htm

Richard Florida

2002 Bohemia and Economic Geography. Journal of Economic Geography 2:55-71.

2008 Who’s Your City?: How the Creative Economy Is Making Where You Live the Most Important Decision of Your Life. Basic Books, New York.

Brandon Gordon

2011 Physical Sympathy: Hip and Sentimentalism in James Baldwin’s Another Country

MFS Modern Fiction Studies 57(1):75-95.

Stephen Greenblatt

1980 Renaissance Self-Fashioning. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Mark Greif

2010a The Hipster in the Mirror. The New York Times 12 November. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/14/books/review/Greif-t.html?pagewanted=1&_r=0

2010b What was the Hipster? New York Magazine 24 October. http://nymag.com/news/features/69129/

Douglas Haddow

2008 Hipster: The Dead End of Western Civilization. Adbusters online.

Rob Horning

2009 The Death of the Hipster. PopMatters http://www.popmatters.com/pm/post/the-death-of-the-hipster-panel/

inCULTURE3

2012 Hipster Revolution, Style of Lifestyle? http://incultur3.com/hipster-revolution-style-or-lifestyle/

Fredric Jameson

1998 Postmodernism and Consumer Society. In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster, pp. 111-125. New Press, New York.

Ben Kessler

2012 Hipsters ‘R Us. In Perspectives by Incongruity, First of the Year: Volume 4, edited by Benj DeMott, pp.70-73. Transaction Press, New Burnswick, New Jersey.

Jake Kinzey

2010 The Sacred and the Profane: An Investigation of Hipsters. Zero Books, Alresford, UK.

Robert Lanham

2009 Look at this Fucking Hipster Basher. The Morning News online. http://www.themorningnews.org/article/look-at-this-fucking-hipster-basher

Richard Lacayo and Ginia Bellafante

2012 If Everyone Is Hip… …Is Anyone Hip? Time 144(6): 48.

Benjamin Lee

2010 Avant-Garde Poetry as Subcultural Practice: Mailer and Di Prima’s Hipsters.

New Literary History 41(4):775-794.

Andrea Levine

2003 The (Jewish) White Negro: Norman Mailer’s Racial Bodies. MELUS 28(2):59-81. (subscription access)

Richard Lloyd

2010 Neo-bohemia: art and commerce in the postindustrial city. 2nd Edition. Taylor and Francis, New York.

Christian Lorentzen

2007 Why the Hipster Must Die. Time Out New York online.

Norman Mailer

1957 The White Negro. Reprinted in Dissent, June 2007. http://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-white-negro-fall-1957

Gary T. Marx

1967 The White Negro and the Negro White. Phylon 28(2):168-177.

Ilie Mitaru

2009 Reconsidering the Hipster: An Acknowledgement of Potentiality. Adbusters online.

Ingrid Monson

1995 The Problem with White Hipness: Race, Gender, and Cultural Conceptions in Jazz Historical Discourse. Journal of the American Musicological Society 48(3):396-422. (subscription access)

Ned Polsky

1967 Hustlers, Beats, and Others. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago.

Steve Shoemaker

1991 Norman Mailer’s “White Negro”: Historical Myth or Mythical History? Twentieth Century Literature 37(3):343-360. (subscription access)

Douglas Taylor

2010 Three Lean Cats in a Hall of Mirrors: James Baldwin, Norman Mailer, and Eldridge Cleaver on Race and Masculinity. Texas Studies in Literature and Language 52(1):70-101

Ingrid M. Tolstad

2006 “Hey Hipster! You are a Hipster!”: An Examination into the Negotiation of Cool Identities. Master of Philosophy Thesis, Department of Social Sciences, University of Oslo.

Images

Berlin hipster image courtesy paulamarttila

Biking fashion image courtesy Lorena Cupcake

Hipster Dust image courtesy Hipster Dust

London Street art image courtesy Chris.Jeriko

Wicker Park cafe image courtesy Joel Mann

Wicker Park shop window image courtesy avrenim_acceber

Williamsburg real estate sign image courtesy EssG

Posted on May 9, 2013, in Uncategorized and tagged #WPLongform, hipsters, wicker park. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

Being a “real” “hipster” entails costs and sacrifices, then, that very few people today have fortitude to pay and make. That’s my take-away. So are you just saying you object to labeling the guy on Milwaukee Ave riding the $1200 Heritage City Bike in $300 Rapha jeans and a tweed cap with a messenger bag and a Wormhole Coffee in a custom holder a hipster? So the nomenclature is wrong? Why does the modern “hipster who’s not really a ‘hipster'” even need a name? And did these “frauds” misappropriate the name or was it attached to them? A big part of this is that, today, with the 1,000,000 opportunities to self express daily and the 10,000,000 platforms for that expression, who’s marginalized anymore, really? A lot of it is faux marginalization. Credential marginalization. So just rename them. You cite a lot of interesting history. I doubt the hipsters one sees in Bucktown know or care about all that. It’s just a urban sartorial expression. Unless you can point to some shared POV and activism about something meaningful or important. You said: “We may only be able to define hipsters because mass culture assiduously constructs them as a consumer demographic or the building blocks for urban engineering, because nearly nobody actually admits to being a hipster.” That makes it sound like you think mass culture is imposed from without, like a Big Brotherish thing rather than being driven and shaped by the consumers themselves. It’s got a very “Advertising makes us buy things we don’t need!” vibe. OTOH, if some dude wants to wear Filson, it’s automatically assumed he’s doing it ironically. Whatever. No one can win. Mom Jeans Guy or $300 Organic Cotton Fair-Trade Authentic Indigo-Dyed Jeans Guy. Basically, everyone’s a hipster so no one is. Why isn;t Mom Jeans Guy the marginalized one now? To over simplify.

I don’t really object to labeling faux marginality, and in fact I agree that much of the contrived outsider status of many contemporary social groups awkwardly conceals wealth and racial privilege. I agree that contemporary hipsters remain oblivious to the heritage of this term or for that matter nearly all historical dimensions of style. But I do think that mass culture named a consumer phenomenon “hipster” in ways that try to manage that demographic and ensure continued consumption; the degree to which hipsters (or any other group) express, on the one hand, some authentic style and, on the other hand, the ideological meanings handed them by mass marketers is ambiguous. I think I can have some sympathy to hipsters’ sense of distinction without accepting that anybody wearing Rapha can be anything but affluent. I do think there is some social movement to be named with some clear material dimensions and patterns, and I certainly think most of us can see it in places like Bucktown, but I also think it hopes to outrun marketers’ efforts to name them and manage their materiality.

This is interesting to me from a “community” standpoint, too. How are we bound and why? What are the controlling “vectors of these groups however we define them? I.e., what things are sine qua nons? Is it politics? A certain POV on how livestock is raised? Taste in music? How flexible are the bounds of any one group? And what beliefs or behaviors cast someone out of that group?

Reblogueó esto en " Una Voz en el Silencio ".

Pingback: The Glory of Berlin – a creative critique