Race and Suburban Homogeneity: The Flanner House Homes and Post-Urban African America

Long Island’s Levittown suburb established the models for material and social homogeneity commonly associated with postwar American suburbs (image MarkGregory007)

In the wake of World War II, suburbs sprang up on the outskirts of American cities, prefabricated and interchangeable homes that reflect postwar social, disciplinary, and material homogeneity. Boosted by Federal Housing Admininstration and veteran’s loans, banks provided loans for 10 million new homes between 1946 and 1953, and Americans set off for the suburbs to settle scores of standardized structures on urban outskirts.

When we imagine such suburbs, we invariably envision solidly middle-class families in the midst of homogeneous neighborhoods, a picture that rarely includes people of color. Access to America’s suburban utopia was denied to most African Americans: realtors, bankers, and urban planners crafted an ideologically distorted, racially restricted American Dream in the suburbs while they championed urban renewal projects that gutted the Black city. The Black experience of postwar suburbanization is a complicated presence on the contemporary landscape: the heritage of urban renewal is reflected in failed projects and abandoned cityscapes that many city governments now want to raze anew. However, an especially interesting dimension of that story is reflected in the Flanner House Homes neighborhood in Indianapolis, Indiana, a history that is now in danger of being forgotten if not displaced.

The suburban experience is routinely painted in homogeneous material and social terms for good reason. Perhaps no suburb better depicts that homogeneity than the original Levittown, the Long Island New York community where the Levitt Brothers built 17,447 homes by 1951. The FHA encouraged suburban planners to restrict the sale of suburban homes to Whites, calling Black residents “adverse influences,” and the Levitts embraced that advice. Bill Levitt rationalized the firm’s racial covenants restricting sales to Whites only with the argument that “As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But the plain fact is that most whites prefer not to live in mixed communities.” In 1960, Levittown’s 82,000 residents included not one African American, making it the single largest universally White community in America.

Levittown was an extreme example that concealed the one-million African Americans who became suburbanites in the 1940s and 1950s. For instance, African Americans had settled north of Detroit in the 1920s on vacant farmland in the Eight Mile-Wyoming area and built modest houses; such “self-built suburbs” constructed by their owners accounted for one-third of all pre-war homes, crafted over time from recycled materials or pre-cut Sears houses and without much planning by local governments. Yet as suburban developments sprang up on city outskirts apprehensive White suburbanites formed municipalities and established anti-Black residency covenants that restricted home sales to Whites (a pattern already tested in Indianapolis itself in the 1920s; compare such covenants in Kansas City and in Seattle).

Men clearing yard spaces around their Flanner House homes (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

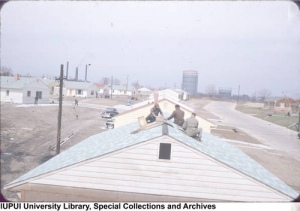

Flanner House builders complete the shell of one of a series of homes. No family could move in until all homes in a section were completed (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

The Flanner House Homes project was one distinctive response to the racist boundaries on post-war suburbs. Flanner House was founded in 1898 as a “settlement house” agency to assist Black residents arriving in 19th-century migrations and subsequently in the Great Migration. The city’s African-American population increased by almost 500% between 1860 and 1870, and in 1900 nearly 10% of the city’s population was African American. Boosted by Southern migration, that population more than doubled in the first two decades of the 20th century, increasing from 15,931 in 1900 to 34,678 in 1920.

In 1936 Tuskegee-trained Cleo Blackburn was hired as the Flanner House director, advocating a strong “self-help” mantra that would remain the Flanner House philosophy through the Depression, post-war decline, and the Civil Rights movement. In 1944 Blackburn directed the construction of a community cannery, health center, nursery, and gardens at its 16th Street headquarters. In 1945 Survey Graphic reported on the new center, indicating that Flanner House “has built a new settlement on the edge of what former U. S. Housing Administrator Nathan Straus called the worst Negro slum in America. It has been instrumental in constructing a new health center nearby. It is operating perhaps the largest community gardening and canning project by and for Negroes in the United States.”

A 1946 study of the neighborhood directed by Blackburn examined 454 Black households on the city’s near-Westside and agreed that the neighborhood was “one of the most unsightly, unsanitary, and deteriorated sectors in the entire city of Indianapolis,” and the homes “needed major repairs and few of them had adequate plumbing facilities.” Blackburn indicated that “the majority had given up hope for any possible improvement,” and he advised that it “is urgently recommended, that the clearance, planning, and redevelopment of this area under the Redevelopment Act of 1945 affords the only hope of correcting the conditions existing in the area. … Immediate steps should be taken by the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission to declare the area blighted and to acquire, clear, and redevelop it.”

Future Flanner House residents shingling their homes (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives)

Created in 1944, the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission was willing to raze the whole of the Black near-Westside, though it had relatively little plan for what to do with the uprooted residents. While most American cities accepted federal funding and built public housing for the scores of families displaced by urban renewal, Indianapolis persistently rebuffed federal funding for such construction under the guise of supporting local contractors. While the African-American near-Westside languished, 9000 new homes were built between 1940 and 1942 to support wartime workforces in Speedway and Warren Township, and 52,000 new homes were built in the city in the 1950’s, but nearly all were in neighborhoods inaccessible to African Americans.

Blackburn proposed tearing down a swath of homes and building “sweat equity” housing in which male head of households constructed their homes and the homes of their neighbors (women could not participate in home construction). The Redevelopment Commission purchased a 178-acre tract north of Crispus Attucks High School in November 1946, referred to as Project A, and after displacing the residents (none of whom were guaranteed acceptance into Flanner House Homes) they turned it over to Blackburn and Flanner House. Construction began in 1950 by a series of men whose families had been exhaustively reviewed by Flanner House, leaving Flanner House solidly peopled by middle-class African Americans.

Flanner House Homes was distinctive for its focus on African Americans in a moment when White urbanites were migrating to the outskirts of the city, but it was simultaneously novel spatially in its simulation of suburban space and its placement within the city. While similar homes were being built on Indianapolis’ rural outskirts, the Flanner House Homes sat just north of the city’s central “Mile Square.” Like many of the suburban homes they borrowed from stylistically, the houses are roughly 975-square foot spaces with standardized footprints and one of four basic street facings. There was nothing that especially distinguished the Flanner House Homes from any house in the White suburbs, and that may well have been Blackburn’s intention. These African-American homes were utterly typical suburban forms that reproduced the very middle-class values that were simultaneously staking a claim to the city’s suburbs. The city’s lone predominately Black suburb was the Grandview community, which was established on the city’s northwest side in the late-1950s. The stylish suburban ranchers and relatively standardized homes were derisively referred to in the local press as the “Golden Ghetto.”

A completed Flanner House homes street looked much like most suburban communities (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

There is nothing especially diasporan about the Flanner House home forms, a direct reflection of the African-American commitment to American middle-class values in particular and the American home ownership dream in particular. The homes might be cast as a reflection of Blackburn’s Tuskegee training, which was profoundly shaped by Booker T. Washington’s accomodationist philosophy, and Blackburn did indeed chart a circumspect and non-confrontational course in local race relations. However, this risks reducing all African-American heritage merely to essentialized diasporan forms and ignores the allure of suburban home ownership and agency in African-American experience.

Flanner House Homes was in some ways a tragic testament to the persistence of racism in Indianapolis. By 1964 the project had built just over 300 homes, and while the city persistently pointed to Flanner House Homes as a success story, it did not remotely address housing problems in Indianapolis and its racial segregation did nothing to address the racism that prevented people of color from moving into other Indianapolis neighborhoods. Realtors refused to show homes to Black households; banks were unwilling to extend loans to African Americans able to pay; and the near-absence of restricted income public housing provided African American few choices for housing. To make matters worse, the imminent arrival of Interstate-65 construction in 1965 would remove 4700 homes, of which roughly half were African American (and in view of Flanner House Homes). Richard Pierce’s compelling study Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970 concludes that when Indianapolis began to enforce laws against housing segregation in the late 1960’s, “Whites no longer needed racial covenants and neighborhood associations to block African American movement into white neighborhoods. The economic gap between whites and African Americans had grown sufficiently that economic realities provided the most effective barrier.”

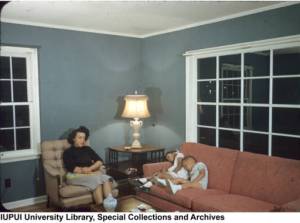

This woman and two children posed in a finished Flanner House home (image IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives).

Flanner Homes was named a National Register Historic District in 2003, but in 2013 Indiana Landmarks named Flanner House Homes and the neighboring Philip’s Temple one of Indiana’s Ten Most Endangered Historic Places. In 2012 the neighborhood first found itself under fire from the Indianapolis Public Schools, which owns Philip’s Temple but hopes to tear down the 1924 church to build a parking lot for Crispus Attucks High School.

The Flanner House homes were recently under fire from the retailer Meijer, who hoped to acquire and demolish 35 of the 181 Flanner House Homes just north of the neighborhood. Meijer removed their bid this week, and the neighborhoods’ resistance and Indiana Landmarks’ advocacy was critical. Nevertheless, the targeting of the neighborhood reflects that the homes’ apparently prosaic form masks their significance as a reflection of color line privileges.

For more details:

Listen to Amos Brown’s interview with residents and local preservations on Afternoons with Amos

Videos of original Flanner House residents and Flanner House can be found at the Flanner House youtube channel

References

Cleo W. Blackburn

1946 A Study of 454 Negro Households in the Redevelopment Area, Indianapolis, Indiana. Unpublished manuscript.

Carolyn M. Brady

1996 Indianapolis at the Time of the Great Migration, 1900-1920. Black History News and Notes 65.

Flanner House Study Committee

1939 The Indianapolis Study. Unpublished manuscript.

David M. P. Freund

2007 Colored Property : State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Kevin Fox Gotham

2000 Urban Space, Restrictive Covenants, and the Origins of Racial Residential Segregation in a US City, 1900-1950. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24(3):616-633.

Bernadette Hanlon

2009 Once the American Dream: Inner-Ring Suburbs of the Metropolitan United States. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Dianne Harris

2006 Seeing the Invisible: Reexamining Race and Vernacular Architecture. Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 13(2):96-105. (subscription access)

Dolores Hayden

2003 Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000. Knopf, New York.

Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission

1954 Annual Report of the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission for 1954. Unpublished manuscript.

Kenneth T. Jackson

1985 Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, New York.

Michael Jones-Correa

2000 The Origins and Diffusion of Racial Restrictive Covenants. Political Science Quarterly 115(4):541-568.

M. Ruth Little

1997 The Other Side of the Tracks: The Middle-Class Neighborhoods that Jim Crow Built in Early-Twentieth-Century North Carolina. In Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture VII, eds. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry, pp, 268-280. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Timothy Maher and Ain Haas

1987 Suburbanizing the City. Sociological Focus 20(4):281-294. (subscription access)

Richard Pierce

2005 Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Charles S. Preston

1946 Local Slum Clearance Plans Advanced by “New Resolution.” Indianapolis Recorder 9 November:1, 3.

Roger William Riis and Webb Waldron

1945 Fortunate City. Survey Graphic XXXTV(8)

Images

Flanner house Construction, yard construction, street scene, and women and children in living room images courtesy Flanner House (Indianapolis, Ind.) Records, 1936-1992, IUPUI University Library Special Collections and Archives

Levittown aerial view image image courtesy MarkGregory007

Posted on May 7, 2013, in Uncategorized and tagged #WPLongform, African American, Flanner House, Indianapolis, suburbs. Bookmark the permalink. 2 Comments.

L’ha ribloggato su Damiano Martorelli's bloge ha commentato:

Un importante contributo (in inglese) sull’America post Seconda Guerra Mondiale sull’urbanesimo delle città americane, ed in particolare degli Afro-Americani, con caratteristiche tipologie edilizie dell’epoca.

Pingback: Urban American Evolution | Eigyou Conseil