Blog Archives

Apocalyptic Imagination and The Walking Dead Fandom

The visual conventions, narrative tropes, and social anxieties tapped by zombie discourses have long had a foothold in some corners of geekdom, and since 2010 AMC’s The Walking Dead has been perhaps the most prominent fandom that reaches far outside comic book nerds. The series premier in October, 2010 netted 5.4 million viewers, a far more successful debut than AMC had dared to imagine. Two weeks after its Halloween premier—and with an agreement to produce a second season immediately secured by AMC–, the New York Times mused that the cable channel was “surveying its new hit about a zombie attack, `The Walking Dead,’ and asking, what went right? On its face, `The Walking Dead’ would seem a hard sell to viewers, with its gory flesh-eating scenes and its comic-book roots.”

The visual conventions, narrative tropes, and social anxieties tapped by zombie discourses have long had a foothold in some corners of geekdom, and since 2010 AMC’s The Walking Dead has been perhaps the most prominent fandom that reaches far outside comic book nerds. The series premier in October, 2010 netted 5.4 million viewers, a far more successful debut than AMC had dared to imagine. Two weeks after its Halloween premier—and with an agreement to produce a second season immediately secured by AMC–, the New York Times mused that the cable channel was “surveying its new hit about a zombie attack, `The Walking Dead,’ and asking, what went right? On its face, `The Walking Dead’ would seem a hard sell to viewers, with its gory flesh-eating scenes and its comic-book roots.”

For many observers The Walking Dead once more underscores the influence of comic culture, since the series is based on a graphic novel series and some of the show’s fans are schooled in comic culture; that is, they arrive with a visual literacy in comic storytelling and likely know the graphic novel’s premise. Others may arrive understanding the visuality and narratives of zombie films, which became a staple of the horror genre after 1968’s Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead a decade later, with a series of films in between and afterward establishing a formula for heightened gore and a tendency to end without a contrived resolution. Yet many Walking Dead fans appear to have migrated to the zombie trope and dystopian tale without any particular connection to comic storytelling or a significant fascination with the undead, and the series’ fandom illuminates how an apocalyptic imagination has expanded into popular culture. Read the rest of this entry

Cosplay and Carnality: Gender, Sexuality, and Geek Subculture

Comic, sci-fi, and anime geeks share an intensive if not obsessive commitment to genre and characters, so it is not surprising that fans so well-schooled in the finest details of characterization can reproduce those characters flawlessly. This weekend a phalanx of Pikachu’s, Catwomen, Storm Troopers, and myriad other comic, video game, and movie characters have invaded the City of Brotherly Love at Wizardworld Philadelphia Comic-Con, one of countless settings in which a host of costumed fans take on the guise of their favorite characters.

Comic, sci-fi, and anime geeks share an intensive if not obsessive commitment to genre and characters, so it is not surprising that fans so well-schooled in the finest details of characterization can reproduce those characters flawlessly. This weekend a phalanx of Pikachu’s, Catwomen, Storm Troopers, and myriad other comic, video game, and movie characters have invaded the City of Brotherly Love at Wizardworld Philadelphia Comic-Con, one of countless settings in which a host of costumed fans take on the guise of their favorite characters.

Cosplay (i.e., costumed play) is a performance in which a fan demonstrates their depth of character understanding, seamless reproduction of character, and creativity and craftsmanship by interpreting and assuming the materiality of that character. Cosplay is visual theatre delivered through costume, pose, and bodily presentation, and cosplayers’ bodies inevitably invoke gender and sexuality, sometimes in subtle forms and other times very assertively. Cosplay is compelling because it exaggerates dimensions of identity in the same way as comics and movies: That is, it takes the essential and familiar threads of class, gender, race, and sexuality and hyperbolizes them. Spiderman, Wonder Woman, or Abraham Lincoln the Vampire Hunter would not be at all interesting if they were “real”; instead, they are alluring because they and their broader narratives capture some compelling dimensions of our own selfhood projected onto distorted realities or pure fantasies.

Cosplay (i.e., costumed play) is a performance in which a fan demonstrates their depth of character understanding, seamless reproduction of character, and creativity and craftsmanship by interpreting and assuming the materiality of that character. Cosplay is visual theatre delivered through costume, pose, and bodily presentation, and cosplayers’ bodies inevitably invoke gender and sexuality, sometimes in subtle forms and other times very assertively. Cosplay is compelling because it exaggerates dimensions of identity in the same way as comics and movies: That is, it takes the essential and familiar threads of class, gender, race, and sexuality and hyperbolizes them. Spiderman, Wonder Woman, or Abraham Lincoln the Vampire Hunter would not be at all interesting if they were “real”; instead, they are alluring because they and their broader narratives capture some compelling dimensions of our own selfhood projected onto distorted realities or pure fantasies.

Characters like Lara Croft (from Tomb Raider), for instance, are strong and independent personalities painted as physically and sexually confident, so there is a legion of women who cosplay Lara Croft. In her video and movie portrayals Lara Croft is modestly clad and physically abundant, aesthetic cues invoking Croft’s confident sexuality and agency, so Lara Croft cosplayers aspire to reproduce her character in personality and physical form. Cosplayers performing characters like Lara Croft self-consciously “perform” gender, while other cosplayers illuminate gender by “cross-play” (e.g., female Doctor Who’s) or assuming the part of an alien (e.g., “She-Bacca”) or things. This cosplay theater obliquely turns a light on our mostly unexamined everyday performances of gender and selfhood.

Yet some observers reduce such cosplay performance to a shallow erotics of scantily clad women manipulatively transfixing straight male nerds. Last year, for instance, Geek Out’s Joe Peacock lamented “fake” cosplay women “pretending to be geeks for attention . . . I’m talking about an attention addict trying to satisfy her ego and feel pretty by infiltrating a community to seek the attention of guys she wouldn’t give the time of day on the street. . . They decide to put on a `hot’ costume, parade around a group of boys notorious for being outcasts that don’t get attention from girls, and feel like a celebrity.”

Yet some observers reduce such cosplay performance to a shallow erotics of scantily clad women manipulatively transfixing straight male nerds. Last year, for instance, Geek Out’s Joe Peacock lamented “fake” cosplay women “pretending to be geeks for attention . . . I’m talking about an attention addict trying to satisfy her ego and feel pretty by infiltrating a community to seek the attention of guys she wouldn’t give the time of day on the street. . . They decide to put on a `hot’ costume, parade around a group of boys notorious for being outcasts that don’t get attention from girls, and feel like a celebrity.”

This clumsy defense of geek subculture makes a familiar appeal to “authenticity” for those who satisfy ambiguous standards for being a “real” geek. Normally this means demonstrating a mastery of a geek oeuvre, which should be represented in the visual performance of well-done cosplay. The mystification of geek authenticity and challenges to cosplaying women’s right to that geek identity reflects a shallow sense of cosplay. A cosplaying body can aesthetically signify beauty, strength, and sexuality in clear ways most of us can “read” visually: in contrast, the ephemeral characteristics we associate with our favorite characters, like intelligence, angst, vulnerability, confidence, deviousness, or selfishness, are much more difficult to perform visually. Cosplay is in most instances a theater without voice whose meanings are completely expressed in visuality and dependent on an audience knowing the visual cues. Those with the oeuvre understanding will recognize most characters and know the qualities of the character, and practiced geeks will know the meanings of genres like steampunk or mecha anime that cosplayers often don.

Shallow critiques of cosplaying sexuality and gender performances evade the complicated gendered politics of cosplay. Much of the cosplaying of powerful female characters in modest dress is an effort of women to secure a symbolic and social foothold in a fan community–as well as a broader social world–that is routinely hostile to their ambitions as both women and geeks. Like any subculture fancying itself distinct from a monolithic mainstream, geeks spend a considerable amount of time patrolling the confines of geek authenticity, but much of that defense takes aim on women. The caricature of geeks as poorly socialized straight men eternally mystified by women hazards becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: a modest but vociferous circle of geek men seems to warily view the entrance of smart, beautiful, and strong women into the geek fold.

Shallow critiques of cosplaying sexuality and gender performances evade the complicated gendered politics of cosplay. Much of the cosplaying of powerful female characters in modest dress is an effort of women to secure a symbolic and social foothold in a fan community–as well as a broader social world–that is routinely hostile to their ambitions as both women and geeks. Like any subculture fancying itself distinct from a monolithic mainstream, geeks spend a considerable amount of time patrolling the confines of geek authenticity, but much of that defense takes aim on women. The caricature of geeks as poorly socialized straight men eternally mystified by women hazards becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: a modest but vociferous circle of geek men seems to warily view the entrance of smart, beautiful, and strong women into the geek fold.

It seems too simplistic to suggest that this use of sexuality in cosplay mechanically perpetuates women’s objectification; nevertheless, much of the aesthetics of cosplay clearly appropriate erotic visual fantasies in which men gaze on women without expecting them to “look back.” Unlike an on-stage performer, a cosplayer is physically in the midst of a swirling audience in which the cosplayer may play their part and then peruse a convention booth as a fan—at some point in the midst of their fierce poses for fellow fans, even Slave Leia needs to have lunch–, but not all audiences distinguish between the cosplayed character and the cosplaying individual. A convention floor is a distinctive space in which character is theatrically explored—cosplayers often acknowledge they would not dress the same way in their everyday lives—but to believe that the codes of everyday life are not going to reach into the convention hall is perhaps overly optimistic. A cosplayer may see themselves as being “in character” and playing the role of a scantily clad and flirtatious character empowered by their sexual agency; audiences on convention floors, though, may respond to visual or vocal cues with personal responses that do not make the distinction between cosplayed character and the cosplayer within.

It seems too simplistic to suggest that this use of sexuality in cosplay mechanically perpetuates women’s objectification; nevertheless, much of the aesthetics of cosplay clearly appropriate erotic visual fantasies in which men gaze on women without expecting them to “look back.” Unlike an on-stage performer, a cosplayer is physically in the midst of a swirling audience in which the cosplayer may play their part and then peruse a convention booth as a fan—at some point in the midst of their fierce poses for fellow fans, even Slave Leia needs to have lunch–, but not all audiences distinguish between the cosplayed character and the cosplaying individual. A convention floor is a distinctive space in which character is theatrically explored—cosplayers often acknowledge they would not dress the same way in their everyday lives—but to believe that the codes of everyday life are not going to reach into the convention hall is perhaps overly optimistic. A cosplayer may see themselves as being “in character” and playing the role of a scantily clad and flirtatious character empowered by their sexual agency; audiences on convention floors, though, may respond to visual or vocal cues with personal responses that do not make the distinction between cosplayed character and the cosplayer within.

An especially overwrought complaint was made by Eisner winner Tony Harris in a rant on cosplay and female fakery in which he proclaimed that “I am so sick and tired of the whole COSPLAY-Chiks. . . . `Hey! Quasi-Pretty-NOT-Hot-Girl, you are more pathetic than the REAL Nerds, who YOU secretly think are REALLY PATHETIC.’” Harris’ facebook tirade on cosplaying women bared a self-loathing insider desperate to secure access to fandom. Peacock and Harris’ tirades reveal anxiety in the face of bodily if not sexual agency that many female and male cosplayers take from assuming the role of strong characters or deviating from normative gendered notions. That strength may aspire to theatrically invoke traits such as intelligence, resourcefulness, deviousness, or self-confidence, but observers’ apprehensions suggest that some audiences will be unable or unwilling to see beyond narrowly defined carnality. A Slave Leia outfit—among the most revealing of all cosplay wardrobes–may be experienced as an empowering performance by a cosplayer, but some audiences will inevitably interpret it as a shallow if not objectified display. Much of the “liberation” celebrated by comics producers, popular cultural marketers, and some cosplayers alike risks reproducing shallow and troubling stereotypes that paint simplistic pictures of carnality.

It is naïve to think that cosplay is not being shaped by a variety of social and marketing forces that influence how we approach cosplay characters. Some conventions offer significant financial incentives for the best cosplayers, and cosplayed characters are walking ads for the companies controlling their images, but for the vast majority of cosplayers the capital is in-group social prestige and individual satisfaction. Conventions seek to attract the most dramatic cosplayers, and on the crowded stages of the most popular conventions some cosplayers capitalize on the visual dimensions of gender and sexuality. It is superficial to conclude simply that “sex sells,” but it is not at all unreasonable to acknowledge that we all respond to displays of sexuality and gender because they are dimensions of selfhood that we all possess.

Cosplay caricatures ultimately risk ignoring or even condoning various forms of sexism, misogyny, and patriarchy in fan communities and broader society. In March the developers of Tomb Raider hosted a booth at the PAX East convention in Boston and invited a group of Lara Croft cosplayers to their booth. A reporter at the booth opened an interview asking the women “How does it feel to be at a convention where none of the men could please you?” When the developers objected to the question, the reporter replied that “the girls were dressing sexy, so they were asking for it.”

Cosplay caricatures ultimately risk ignoring or even condoning various forms of sexism, misogyny, and patriarchy in fan communities and broader society. In March the developers of Tomb Raider hosted a booth at the PAX East convention in Boston and invited a group of Lara Croft cosplayers to their booth. A reporter at the booth opened an interview asking the women “How does it feel to be at a convention where none of the men could please you?” When the developers objected to the question, the reporter replied that “the girls were dressing sexy, so they were asking for it.”

In some ways the distinctive masquerade of cosplay may seem to license some people to behave boorishly or acknowledge their deep-seated prejudices, but gendered cosplay tensions reveal various forms of sexism that course throughout geek culture and mainstream life. We can find comparable ideologies embedded in video gaming and comics that reproduce the same inequities in popular culture, so geek subculture and cosplaying are simply threads in a broad social fabric.

We risk forgetting that in nearly every fan’s hands cosplay is theatrical if not reverential fanhood, a genuine show of love for a character and a community of like-minded people even as it is a consequential effort to know oneself. The act of being “in” Lara Croft, Darth Vader, or Captain America’s character inevitably involves knowing oneself as well and being comfortable in our own skin. People are forever “putting on” their identities in material culture, social practice, and imagination, and cosplay simply brings that out into the open in a spectacular if distorted reflection.

References

Judith Butler

1999 Gender Trouble. Routledge, New York.

Jin-Shiow Chen

2007 A Study of Fan Culture: Adolescent Experiences with Animé/manga Doujinshi and Cosplay in Taiwan. Visual Arts Research 33, No. 1(64):14-24. (subscription access)

Scott Duchesne

2010 Stardom/Fandom: Celebrity and Fan Tribute Performance. Canadian Theatre Review 141: 21-27. (subscription access)

Michelle L. McCudden

2011. Degrees of Fandom: Authenticity & Hierarchy in the Age of Media Convergence. PhD Dissertation, University of Kansas.

Kazumi Nagaike and Kaori Yoshida

2011 Becoming and Performing the Self and the Other: Fetishism, Fantasy, and Sexuality of Cosplay in Japanese Girls’/Women’s Manga. Asia Pacific World 2(2):22-43. (subscription access).

Craig Norris and Jason Bainbridge

2009 Selling Otaku? Mapping the Relationship between Industry and Fandom in the Australian Cosplay Scene. Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 20.

Mark Leonard Watts

2008 The imagined life of an Otaku collector, or to be a Cosplay star. PhD Dissertation, Auckland University of Technology.

Theresa Winge

2006 Costuming the imagination: Origins of anime and manga cosplay. Mechademia 1(1):65-76. (subscription access)

All images by author at Wizard World Philadelphia Comic Con

Geek Ink: Geek Tattoos and Consumer Culture

To be geek is no longer an especially unique or stigmatizing proclamation. The term geek is often somewhat sloppily used to refer to a broad range of people with some fervent attraction to something; while it is not necessary to establish an inflexible definition for geek, it seems to distinguish social groups sharing a fervent collective commitment to fan practices and discourses: those might revolve around comics, science fiction, gaming, or nearly any other dimension of popular culture that fashions social interactions and consumption.

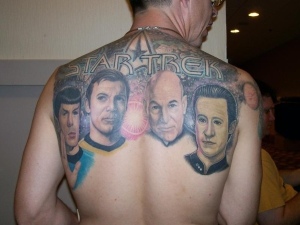

In the context of consumer culture being geek risks losing its distinction as marketers package geek symbols for the masses, so geeks aspire to race ahead of the “mainstream,” seeking out the creative, arcane, and specialized and preserving geek distinction before it falls victim to mass marketing. The challenge contemporary subcultures face is to maintain social practices and material style in opposition to a homogenizing marketplace that reduces such practices and things to mass-produced—and commonplace–commodities. Batman, Star Wars, Star Trek, and Spiderman are now brands in the sense that they may be homogenizing marketing symbols as much as they are symbols of distinction or resistance.

Geeks’ distinction is not simply a matter of material consumption: geek standing is secured by informed thinking through and mastery of obscure knowledge, so it is fundamentally social. The notion that such social practices define a “geek culture” risks lapsing into marketing caricatures, and it also hazards a contrived authenticity that poses absolute boundaries between geeks and non-geeks. Nevertheless, there are some genuine social distinctions, and consumption is clearly a key dimension of staking a claim to geek status, with a variety of material culture—t-shirts, toys, posters, shoes—offering up geek symbols recognizable to nearly any audience.

Tattoos are commodities that embed symbolic capital in our skin, rendering our body a consumable sign to be “read,” however tattoos are distinctive consumables. On the one hand, tattoos are commodities that routinely represent popular cultural motifs if not branded symbols, and tattoos no longer represent dramatic deviance from the mainstream (21% of American adults in 2012 had at least one tattoo). On the other hand, tattoos are not mass-produced commodities, and they represent some individually chosen symbolism. Tattoos fabricate consumer selfhood, but they involve individual selection of the symbols, a narrative of the process of getting the tattoo, and genuine permanence.

Science fiction and comics provide many rich franchise symbols. Batman, for instance, provides a host of Bat logos and symbols from comics, the television show, a series of movies, and even games. Like the most cherished sci-fi and comic franchises, a Batman symbol is recognizable beyond the confines of geek circles, but that broad currency risks undermining the symbol’s geek meanings. A geek tattoo is most powerful as subcultural capital when it invokes a novel or obscure symbol distinct to a subcultural collective; in a geek’s skin, these deepest symbols materialize knowledge, creativity, and devotion, if not love.

Much like Batman, Doctor Who provides a host of symbols including the TARDIS, Daleks, K-9, and the Doctors as well as a host of catchphrases for the textually inclined. After over a half-century of programming, Doctor Who symbols are familiar amongst geeks, and a completely unscientific survey of online Who tattoos suggests that the TARDIS is indeed the most common motif amongst Who tattoos. The TARDIS has the attraction of providing a form a consumer and tattoo artist can individualize, and being a literal shape that fits nicely along various reaches of the body, including backs, arms, ankles, calves, and even the lower back.

This TARDIS tattoo wraps itself in the Fourth Doctor’s iconic scarf (image Jon Reed, All Saints Tattoo Austin TX).

A TARDIS tattoo has widespread apprehensibility, yet at some point it risks becoming so commonplace that it loses its novelty. A tattoo hazards losing its claim to subcultural and artistic authenticity as well as its individual distinction if it simply reproduces a mass motif or invokes celebrity. Batman’s masked hero makes little appeal to the personality of Bruce Wayne or the actors who have played the Caped Crusader, and Star Wars provides similarly de-personalized characters like Darth Vader, Ewoks, or the Death Star. Nevertheless, in some cases it is difficult to separate a personality from a character (e.g., Heath Ledger’s Joker), and some celebrities like Marilyn Monroe may function symbolically as characters more than homages to celebrity. Doctor Who tattoos sometimes pay homage to the Doctors (e.g., the iconic fourth Doctor Tom Baker, or even all the Doctors). The most recent Doctors (David Tennant and Matt Smith) appear in some tattoos as symbols of “geek chic,” a self-consciously geek fashion that has become closely associated with both Tennant and Smith. However, as a concrete style geek chic aspires to take an unfeigned look and turn it into a superficial consumer aesthetic with no real claim to geek subculture. Unlike an original artistic motif, a popular symbol or a personality tattoo hazards losing geek consequence if its lack of aesthetic novelty undercuts the subcultural and personal meaningfulness of a tattoo.

The audience for a geeky tattoo is perhaps on some level other geeks or the uninitiated, but tattoos are not purely performative; that is, a tattoo in many ways is a soliloquy of selfhood as much as it is a display of geekhood. Tattoos establish bonds with like-minded others and materialize personal narratives, but they also are inchoate personal imaginings of who a consumer fancies themselves to be, rich evocative symbols of particular individual and social properties a consumer associates with a motif. A geek consumer articulates their sense of novelty, creativity, and personality to themselves in their commitment to a tattooed symbol that fashions themselves as “authentically” geek.

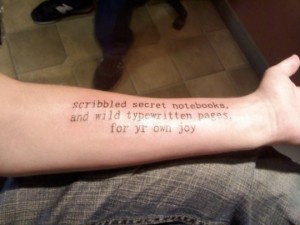

Where sci-fi, comic, and movie geeks raid popular cultural discourses for their tattoo symbols, literature geeks mine texts for quotations. Literary tattoos celebrate rich, evocative turns of phrase rather than abstract symbols, but they still have an aesthetic dimension, minimally in fonts but often in symbols paired with textual quotes. No literary tattoo seems more common than Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five quote “So it Goes.” The flexible phrase appears in the book over a hundred times, and it is especially attractive as a tattoo for its succinctness (so it can appear in many different body spots), and it invokes a classic cult novel. Like popular cultural tattoos, literary geeks’ tattoos demonstrate knowledge of a text, carefully negotiating between celebrating a too-familiar quote or finding one that is overly arcane.

The stereotype of an obscure, anti-social, style-less, and isolated geek culture has been undone by a consumer culture that markets geek style to and has more overlap with popular culture than most geeks acknowledge. The projection of that style beyond narrow geek circles sometimes strikes apprehension in the imagination of geeks aspiring to preserve their sense of material and social distinction. Tattoos aspire to capture that geek symbolism in ways that preserve its distinctiveness without lapsing into the appearance of consumer homogenization. What it means to be geek is utterly dynamic, contextual, and defined in constant social interaction and negotiation within and against mass marketing. Tattoos—personal, creative, idiosyncratic, permanent—provide one mechanism anchoring geek selfhood.

Some images take geek motifs like the Borg and project them onto other symbols, in this case creating an Abe Lincoln of Borg (image Geeky Tattoos)

References

Anders Bengtsson, Jacob Osterberg, and Dannie Kjedlgaard

2005 Prisoners in Paradise: Subcultural Resistance to the Marketization of Tattooing. Consumption, Markets and Culture 8(3):261-274.

Christina Goulding, John Follett, Michael Saren, and Pauline MacLaren

2004 Process and meaning in “getting a tattoo.” Advances in Consumer Research 31(1):279-284.

Paul Lopes

2009 Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Maurice Patterson and Jonathan Schroeder

2010 Borderlines: Skin, tattoos and consumer culture theory. Marketing Theory 10(3):253–267.

Victoria Pitts

2003 In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification. Palgrave Macmillan, Gordonsville, Virginia.

Enid Schildkrout

2004 Inscribing the Body. Annual Review of Anthropology 33(1):319-44.

William L. Svitavsky

2001 Geek Culture: An Annotated Interdisciplinary Bibliography. The Bulletin of Bibliography 58(2):101-108.

Jason Tocci

2007 The Well-Dressed Geek: Media Appropriation and Subcultural Style. Paper presented at MiT5, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Anne M. Velliquette, Jeff B. Murray, and Elizabeth H. Creyer

1998 The Tattoo Renaissance: An Ethnographic Account of Symbolic Consumer Behavior. Advances in Consumer Research 25:461-467.

Rebecca Williams

2011 Desiring the Doctor: Identity, Genre, and Gender in Online Fandom. In British Science Fiction Film and Television: Critical Essays, edited by Tobias Hochscherf and James Leggott, pp.167-177. McFarland and Company, Jefferson, North Carolina.

Amy Wilkins

2008 Wannabes, Goths, and Christians: The Boundaries of Sex, Style, and Status. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Image

Abe Lincoln of Borg image Geeky tattoos

David Tennant image from Nerd tattoos

Doctor Who villains image Geeky Tattoos

Jack Kerouac quote from Tips for Spontaneous Prose image from contrariwise

Star Trek tattoo image Tissy Tech

TARDIS and Fourth Doctor Scarf image Jon Reed by All Saints Tattoo

Time Seal image Benchilada

Yoda tattoo image Tissy Tech