Blog Archives

Saving Doctor Who: Transience, Canon, and the Missing Episodes

Geekdom has spent much of this year celebrating the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who, which is one of the most prominent and long-lasting of all popular cultural fandoms. The impending regeneration of the 11th Doctor at year’s end and the November showing of Who’s 50th anniversary show have lent some elevated excitement to Who followers. Yet perhaps the most interesting development in Who fandom is the search for lost Doctor Who programs destroyed in the 1960s and 1970s. Television shows like Doctor Who were once destroyed as a standard practice, and the lost episodes have since become Who grail.

In an otherwise transient popular culture, Who fans hope to recover and breathe new complexity into an oeuvre that is already exceptionally complex. For various fans, the missing episodes may harbor some new insights into one of television’s most deconstructed series; for many the search itself and the scholarship on the lost episodes is a central dimension of Who’s committed fandom. The corporations seeking out the same episodes are eager to sustain fan interest in the missing programs (BBC had a “Treasure Hunt” program seeking lost shows), but corporate interests revolve around the profits such shows may harbor in a renewed lease on life as DVD’s and iTunes downloads. That question of what is meaningful is actually quite similar to the skepticism often directed at scholarship (including archaeology) that seeks out, preserves, and celebrates apparently mundane everyday life. Read the rest of this entry

Geek Tees: T-Shirts and Geek Culture

Most pictures of the geek experience highlight the aesthetic and material visibility of geeks: that is, we can “see” geeks, who signal their social distinctions with material style ranging from clothes to super-hero statues to backpacks to body form. Among the pantheon of geek material goods, perhaps no element is more visible or common than the prosaic t-shirt, and geek t-shirts provide a compelling if somewhat novel mechanism to illuminate geek-ness, the notion of “geek culture,” and the intersection of geeks, style, and marketing.

The idea of a geek culture carries with it some intellectual baggage rooted in conventional anthropological definitions of culture, and the problem of defining geek “culture” is common to definitions of many other contemporary social collectives. Anthropologists have been destabilizing the idea of culture—the very concept that defines the discipline—since the 1970’s, complicating the facile distinction between the West and the Other that characterized colonial analyses of the world. We live in a moment in which something approximating a global consumer culture has collapsed how we see difference, imagine community, and craft distinction, leaving us in an interconnected world in which “us” and “them” are not especially useful polarizations.

Culture is a somewhat mechanical concept if we approach it in terms of bounded membership (e.g., “real” geeks and poseurs) or simply oppose it to some caricatured foil (e.g., geeks as a contrast to the “mainstream,” “sports/jock culture,” or some other stereotype of “normality”). For some anthropologists, culture is produced for specific sorts of social reasons; that is, culture is not something essential like where you were born or your skin color, but it is instead constructed to represent distinction and create a sense of separateness. When geeks appropriate the moniker of “culture,” they perhaps stake a clumsy claim to the social legitimacy, authenticity, and distinction associated with traditional definitions of culture. Social groups like geeks routinely celebrate themselves as a “culture” because that concept distinguishes them as a unified and distinct group separated from the materiality, taste, and practices of the masses. We can literally see those differences in mundane things like distinctive t-shirts.

Zombies and Doctor Who are among the most popular geek motifs, sometimes even crossing over onto the same shirt (image ShantyShawn, Red Bubble)

Few elements of geek material culture are more common than the t-shirt. Every convention is now crowded by a host of merchants selling every possible geek motif shirt; specialty stores and increasingly more mainstream shops hawk geeky t-shirts; and many more firms and individual sellers cover the internet with countless geek icons (e.g., Star Wars), crossovers (featuring two or more franchises), and individual creations paying homage to the likes of zombies, Lovecraft, and Minecraft.

The emergence of the branded t-shirt is a relatively recent phenomenon. The superhero and sci-fi shirt market once stopped at middle school sizes just as Batman jammies transitioned to teen sizes and adult styles. Concert t-shirts—the obscenely over-priced confirmation you did indeed see Grand Funk Railroad—were one deviation from that t-shirt market (the first concert souvenir shirt was apparently a 1956 Elvis shirt, and the Monkees sold shirts on their 1967 American tour), and some resorts began to produce branded shirts advertising their resorts in the 1950’s. Popular franchises like Planet of the Apes and Doctor Who were long tied to branded goods like toys, but adult clothing was an uncommon branded item. Kids’ clothing was sold in department stores alongside other children’s fashions, and toys had a dedicated department in most stores, but adult t-shirts were mostly available only as undecorated undergarments in the men’s underwear section.

An emerging marketplace in the 1980s and into the 1990s was sci-fi conventions. Fans had gathered at science fiction conventions like WorldCon (1939) since World War II, but they were joined by many more fans with the introduction of Gen Con (gaming) in 1968, Comic Con in 1970, Eurocon (European sci-fi) in 1972, the World Fantasy Convention in 1975, Comiket (anime/manga) in 1975, the North American Science Fiction Convention in 1975, DragonCon (multiple genres) in 1987, and a host of more specialized and regional conferences and ever-more comic and sci-fi shows in the past 20 years.

Fueled by the explosion in geek conventions, the most significant expansion of the t-shirt market—and many other geek commodities—came in the past 20 years, and much of it has been driven by internet sales and marketers’ increasingly aggressive appeal to geek consumers. The scatter of homemade silk screens and DIY shirts made in the 1970s and 1980s now pale in comparison to the legion of shirts that are marketed internationally online.

As with all things geek, the conditions that qualify a shirt as geek are somewhat ambiguous. Mass marketers aspire to manage brand symbolism, so somewhere in the flood of officially branded Iron Man or Walking Dead shirts there are corporate efforts to structure the meaning of the franchise and manage fan demand for the goods. In a do-it-yourself moment, though, a crowd of modest artists, fans, and marketers appropriate those brands; legally we cannot make and sell Portal shirts, but the corporate legal effort of shutting down every modest seller on Red Bubble and ebay may not be worth the cost, and it is certainly counter-productive in fan communities. The result is an absolute flood of shirts in every possible motif, some officially sanctioned and many more fan homages.

Within days of the President’s reference to a “Jedi Mind Meld,” this shirt appeared placing the POTUS in both Star Wars and Star Trek (image from T Shirt Laundry)

This flooded market has yielded symbolic geek riches. Perhaps the central geek value that shapes the meaning of t-shirts is novelty. Geeks value clever and novel plays on shared symbols—for instance, the “Ewoking Dead” hybridizing two geek franchises (zombie crossovers range from Peanuts to Hello Kitty to Tron), Mad X Men, or various interpretations of icon scenes like ET riding an airborne bike in the moonlight. A “good” shirt is inevitably a subjective notion, but the most compelling motifs seize on geek franchises (e.g., the universe of Doctor Who shirts knows no bounds), employ phrases familiar only to insiders, or are timely (e.g., within days of his reference to a “Jedi Mind Meld,” a t-shirt appeared featuring a Vulcan Obama in a Jedi robe; a “Red Wedding” shirt from Game of Thrones was available the day following the episode).

At major conventions it is increasingly more common to find that very few people are wearing the same t-shirts. The sales floor of every convention is always its busiest space, and a series of web pages like T-Shirt Roundup and Hide Your Arms do nothing but inventory t-shirts for sale on any given day. The highest geek fashion complement today may be “Where did you get that shirt?,” yet this is a tribute to shopping resourcefulness as much as it is flattery to taste: demonstrating t-shirt style requires a geek to be as good a shopper as many of the masses so commonly dismissed by geeks, so t-shirts underscore the geek immersion in consumer culture. Certainly many t-shirt sellers are individuals managing modest operations and celebrating their favorite geekery, but a host of firms now sell a vast volume of t-shirts and assorted commodities explicitly marketed as “geek.”

A t-shirt is perhaps a somewhat distinctive geek commodity, since it is worn outside the confines of conventions and comic shops and confirms in public space the consumer’s attraction to Game of Thrones, Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Sherlock, Firefly, Lord of the Rings, and myriad other geek realms and franchises. Some symbols have pretty universal recognition (e.g., Superman and Batman), but others are much more of a niche that may be incomprehensible beyond geek circles (e.g., the Torchwood Institute symbol). For some observers these shirts are homing signals that identify fellow geeks and weed out those who cannot recite Roy Batty’s final soliloquy. Nevertheless, such symbols are not purely “other-directed” and meant to establish affinities with other geeks: geek symbols are perhaps equally if not more important for how they make the consumer feel. Batman, for instance, could be a sign of law-and-order, rebellion, or style, and none of those meanings are exclusive to each other or necessarily even articulate.

We can circumspectly acknowledge a body of social practices that distinguishes “geek culture,” but at the same time it is firmly embedded in broader marketing patterns and consumer values. The notion of a clearly defined mainstream culture against which geeks are contrasted is mostly a rhetorical maneuver that evades the deep impression of geeks in consumer culture, if not their centrality in that society. Any efforts to define geeks—call it a culture, subculture, post-subculture, tribe, or any other term–need to examine who we imagine ourselves to be; what socially unites a circle of people attracted to games, sci-fi, cosplay, and comics; and how dominant ideologies and market structure shape the expression of geek selfhood. Culture is partly an idea that imagines self and others; it is partly a document of shared experiences, a common everyday life; and it is partly a set of structural material conditions. Any reflective understanding of geeks needs to examine all of these interconnected dimensions of geekhood and contemporary life.

References

Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson

1992 Beyond “Culture”: Space, Identity, and the Politics of Difference. Cultural Anthropology 7 (1):6-23. (subscription access)

J.A. McArthur

2009 Digital Subculture: A Geek Meaning of Style. Journal of Communication Inquiry 33(1): 58-70. (subscription access)

Jason Tocci

2007 The Well-Dressed Geek: Media Appropriation and Subcultural Style. Paper presented at MiT5, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (29 April).

Johnny Yu

2007 Looking Inside Out: A Sociology of Knowledge and Ignorance of Geekness. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 5(2): 41-50.

Images

Wizard World images from author

Dawn of the Doctor shirt image from ShantyShawn on Red Bubble

Doctor Who Hearts image from okse on Red Bubble

ET/Aliens shirt image from runstop on Red Bubble

Jedi mind Meld image from T Shirt laundry

Geek Ink: Geek Tattoos and Consumer Culture

To be geek is no longer an especially unique or stigmatizing proclamation. The term geek is often somewhat sloppily used to refer to a broad range of people with some fervent attraction to something; while it is not necessary to establish an inflexible definition for geek, it seems to distinguish social groups sharing a fervent collective commitment to fan practices and discourses: those might revolve around comics, science fiction, gaming, or nearly any other dimension of popular culture that fashions social interactions and consumption.

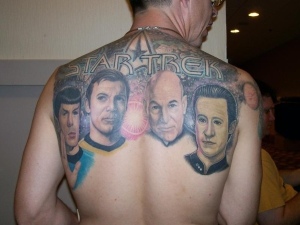

In the context of consumer culture being geek risks losing its distinction as marketers package geek symbols for the masses, so geeks aspire to race ahead of the “mainstream,” seeking out the creative, arcane, and specialized and preserving geek distinction before it falls victim to mass marketing. The challenge contemporary subcultures face is to maintain social practices and material style in opposition to a homogenizing marketplace that reduces such practices and things to mass-produced—and commonplace–commodities. Batman, Star Wars, Star Trek, and Spiderman are now brands in the sense that they may be homogenizing marketing symbols as much as they are symbols of distinction or resistance.

Geeks’ distinction is not simply a matter of material consumption: geek standing is secured by informed thinking through and mastery of obscure knowledge, so it is fundamentally social. The notion that such social practices define a “geek culture” risks lapsing into marketing caricatures, and it also hazards a contrived authenticity that poses absolute boundaries between geeks and non-geeks. Nevertheless, there are some genuine social distinctions, and consumption is clearly a key dimension of staking a claim to geek status, with a variety of material culture—t-shirts, toys, posters, shoes—offering up geek symbols recognizable to nearly any audience.

Tattoos are commodities that embed symbolic capital in our skin, rendering our body a consumable sign to be “read,” however tattoos are distinctive consumables. On the one hand, tattoos are commodities that routinely represent popular cultural motifs if not branded symbols, and tattoos no longer represent dramatic deviance from the mainstream (21% of American adults in 2012 had at least one tattoo). On the other hand, tattoos are not mass-produced commodities, and they represent some individually chosen symbolism. Tattoos fabricate consumer selfhood, but they involve individual selection of the symbols, a narrative of the process of getting the tattoo, and genuine permanence.

Science fiction and comics provide many rich franchise symbols. Batman, for instance, provides a host of Bat logos and symbols from comics, the television show, a series of movies, and even games. Like the most cherished sci-fi and comic franchises, a Batman symbol is recognizable beyond the confines of geek circles, but that broad currency risks undermining the symbol’s geek meanings. A geek tattoo is most powerful as subcultural capital when it invokes a novel or obscure symbol distinct to a subcultural collective; in a geek’s skin, these deepest symbols materialize knowledge, creativity, and devotion, if not love.

Much like Batman, Doctor Who provides a host of symbols including the TARDIS, Daleks, K-9, and the Doctors as well as a host of catchphrases for the textually inclined. After over a half-century of programming, Doctor Who symbols are familiar amongst geeks, and a completely unscientific survey of online Who tattoos suggests that the TARDIS is indeed the most common motif amongst Who tattoos. The TARDIS has the attraction of providing a form a consumer and tattoo artist can individualize, and being a literal shape that fits nicely along various reaches of the body, including backs, arms, ankles, calves, and even the lower back.

This TARDIS tattoo wraps itself in the Fourth Doctor’s iconic scarf (image Jon Reed, All Saints Tattoo Austin TX).

A TARDIS tattoo has widespread apprehensibility, yet at some point it risks becoming so commonplace that it loses its novelty. A tattoo hazards losing its claim to subcultural and artistic authenticity as well as its individual distinction if it simply reproduces a mass motif or invokes celebrity. Batman’s masked hero makes little appeal to the personality of Bruce Wayne or the actors who have played the Caped Crusader, and Star Wars provides similarly de-personalized characters like Darth Vader, Ewoks, or the Death Star. Nevertheless, in some cases it is difficult to separate a personality from a character (e.g., Heath Ledger’s Joker), and some celebrities like Marilyn Monroe may function symbolically as characters more than homages to celebrity. Doctor Who tattoos sometimes pay homage to the Doctors (e.g., the iconic fourth Doctor Tom Baker, or even all the Doctors). The most recent Doctors (David Tennant and Matt Smith) appear in some tattoos as symbols of “geek chic,” a self-consciously geek fashion that has become closely associated with both Tennant and Smith. However, as a concrete style geek chic aspires to take an unfeigned look and turn it into a superficial consumer aesthetic with no real claim to geek subculture. Unlike an original artistic motif, a popular symbol or a personality tattoo hazards losing geek consequence if its lack of aesthetic novelty undercuts the subcultural and personal meaningfulness of a tattoo.

The audience for a geeky tattoo is perhaps on some level other geeks or the uninitiated, but tattoos are not purely performative; that is, a tattoo in many ways is a soliloquy of selfhood as much as it is a display of geekhood. Tattoos establish bonds with like-minded others and materialize personal narratives, but they also are inchoate personal imaginings of who a consumer fancies themselves to be, rich evocative symbols of particular individual and social properties a consumer associates with a motif. A geek consumer articulates their sense of novelty, creativity, and personality to themselves in their commitment to a tattooed symbol that fashions themselves as “authentically” geek.

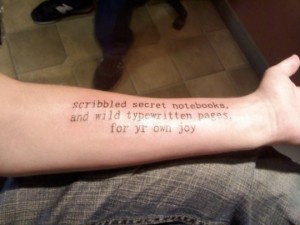

Where sci-fi, comic, and movie geeks raid popular cultural discourses for their tattoo symbols, literature geeks mine texts for quotations. Literary tattoos celebrate rich, evocative turns of phrase rather than abstract symbols, but they still have an aesthetic dimension, minimally in fonts but often in symbols paired with textual quotes. No literary tattoo seems more common than Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five quote “So it Goes.” The flexible phrase appears in the book over a hundred times, and it is especially attractive as a tattoo for its succinctness (so it can appear in many different body spots), and it invokes a classic cult novel. Like popular cultural tattoos, literary geeks’ tattoos demonstrate knowledge of a text, carefully negotiating between celebrating a too-familiar quote or finding one that is overly arcane.

The stereotype of an obscure, anti-social, style-less, and isolated geek culture has been undone by a consumer culture that markets geek style to and has more overlap with popular culture than most geeks acknowledge. The projection of that style beyond narrow geek circles sometimes strikes apprehension in the imagination of geeks aspiring to preserve their sense of material and social distinction. Tattoos aspire to capture that geek symbolism in ways that preserve its distinctiveness without lapsing into the appearance of consumer homogenization. What it means to be geek is utterly dynamic, contextual, and defined in constant social interaction and negotiation within and against mass marketing. Tattoos—personal, creative, idiosyncratic, permanent—provide one mechanism anchoring geek selfhood.

Some images take geek motifs like the Borg and project them onto other symbols, in this case creating an Abe Lincoln of Borg (image Geeky Tattoos)

References

Anders Bengtsson, Jacob Osterberg, and Dannie Kjedlgaard

2005 Prisoners in Paradise: Subcultural Resistance to the Marketization of Tattooing. Consumption, Markets and Culture 8(3):261-274.

Christina Goulding, John Follett, Michael Saren, and Pauline MacLaren

2004 Process and meaning in “getting a tattoo.” Advances in Consumer Research 31(1):279-284.

Paul Lopes

2009 Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Maurice Patterson and Jonathan Schroeder

2010 Borderlines: Skin, tattoos and consumer culture theory. Marketing Theory 10(3):253–267.

Victoria Pitts

2003 In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification. Palgrave Macmillan, Gordonsville, Virginia.

Enid Schildkrout

2004 Inscribing the Body. Annual Review of Anthropology 33(1):319-44.

William L. Svitavsky

2001 Geek Culture: An Annotated Interdisciplinary Bibliography. The Bulletin of Bibliography 58(2):101-108.

Jason Tocci

2007 The Well-Dressed Geek: Media Appropriation and Subcultural Style. Paper presented at MiT5, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Anne M. Velliquette, Jeff B. Murray, and Elizabeth H. Creyer

1998 The Tattoo Renaissance: An Ethnographic Account of Symbolic Consumer Behavior. Advances in Consumer Research 25:461-467.

Rebecca Williams

2011 Desiring the Doctor: Identity, Genre, and Gender in Online Fandom. In British Science Fiction Film and Television: Critical Essays, edited by Tobias Hochscherf and James Leggott, pp.167-177. McFarland and Company, Jefferson, North Carolina.

Amy Wilkins

2008 Wannabes, Goths, and Christians: The Boundaries of Sex, Style, and Status. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Image

Abe Lincoln of Borg image Geeky tattoos

David Tennant image from Nerd tattoos

Doctor Who villains image Geeky Tattoos

Jack Kerouac quote from Tips for Spontaneous Prose image from contrariwise

Star Trek tattoo image Tissy Tech

TARDIS and Fourth Doctor Scarf image Jon Reed by All Saints Tattoo

Time Seal image Benchilada

Yoda tattoo image Tissy Tech

Consuming Geeks: Subculture and the Marketing of Doctor Who

This month the most committed Doctor Who fans descended on the Los Angeles Marriott for Gallifrey One, the 24th annual gathering of Whovians in Los Angeles. On the one hand, these Doctor Who fans share a commonplace geek satisfaction with their sense of distinction from the mainstream. A Who fan who grew up in Detroit noted that “As kids we loved anything Science Fiction from Star Trek to Space 1999 … we were weirdoes. But that was okay. It was a badge of honour. Really. SF was not as `popular’ then as it seems to be now, and British SF was probably deemed even odder.” Patton Oswalt’s analysis of contemporary geeks inventories a typical range of geek obsessions confirming that “I was never going to play sports, and girls were an uncrackable code. So, yeah—I had time to collect every Star Wars action figure, learn the Three Laws of Robotics, memorize Roy Batty’s speech from the end of Blade Runner, and classify each monster’s abilities and weaknesses in TSR Hobbies’ Monster Manual.” Oswalt admits the satisfaction he got from “quietly being tuned in to something dark, complicated, and unknown just beneath the topsoil of popularity.”

On the other hand, though, Oswalt is among the observers who have prophesied the death of that very subculture, lamenting “Fast-forward to now: Boba Fett’s helmet emblazoned on sleeveless T-shirts worn by gym douches hefting dumbbells. The Glee kids performing the songs from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. And Toad the Wet Sprocket, a band that took its name from a Monty Python riff, joining the permanent soundtrack of a night out at Bennigan’s. Our below-the-topsoil passions have been rudely dug up and displayed in the noonday sun.”

Once utterly invisible outside a circle of the most committed fans, in 2012 Entertainment Weekly heralded Doctor Who as a “global geek obsession”; this week al-Jazeera bought three seasons of Doctor Who; and in 2011 Doctor Who’s sixth season was the most downloaded television season on iTunes. In some observers’ minds, this long-awaited ascent to mainstream popularity spells the death rites for the Doctor Who geek as a distinctive voice and identity. Contemporary Doctor Who fans risk being not marginal at all, and in this respect they share quite a lot with comic books fans, science fiction geeks, anime fans, or role-playing gamers who all have secured significant footholds in popular culture: San Diego Comic-Con is now among the most influential of all mass media and marketing events; television is littered with a variety of series that openly invoke science fiction and celebrate geeks; anime and manga aesthetics pervade popular culture; and role playing games have become a massive industry whose impression can be seen all over popular culture. Once embracing something esoteric and disinteresting to the masses, geeks now have effected a complete reversal that witnesses them as the leading edge of style: rather than being disparaged as outcasts, geeks have become an energizing fringe fueling mass culture.

“Geek” is commonly referred to as a “subculture,” but that term is sloppily wielded in popular usage and tends to refer to nearly any distinctive social collective. In scholarly terms a subculture reflects and expresses social contradictions through oppositional style and social practice. Subcultures use material style and social practice to express and attempt to resolve the contradictions of mainstream culture: that is, weeping angel t-shirts, “Bad Wolf” bumper stickers, and sonic screwdrivers are utterly politicized symbols signaling social identity and distance from mainstream social codes. Doctor Who fans, like most members of self-identified subcultures, are energized by their self-perceived marginalization, if not the belief that they have been denied some unfettered experience by the normative values of “mainstream” society.

Not every geek is eager to relinquish their distinctions from the mainstream. Blogger Maryann Johanson, for instance, prophesied the underside of Doctor Who’s broader following when she lamented retailer Hot Topic’s embrace of Doctor Who merchandise: “Hot Topic is a U.S. chain store that pops up in malls to serve kids who want to buy a premanufactured notion of cool instead of developing their own personalities. If the vice president and general merchandise manager for Hot Topic is excited about Doctor Who, it can only mean that the Doctor is on the verge of tedious ubiquitousness in America.”

Johanson seems to be apprehensive that the unfeigned passion fans have invested in Doctor Who will be undone by the marketplace. Her wariness of “premanufactured cool” suggests the marketplace will inevitably redefine consequential if not deviant symbolism and reduce it to transparently commodified edginess. This is precisely what Dick Hebdige cautioned was the universal fate of subcultures. Hebdige’s classic study of punk style argued that subcultural aesthetics are re-defined by marketers in ways that neutralize anxiety-invoking distinctions. Those subcultural material forms—goth makeup, Rastafarian garb, hippie tie-dye shirts–become simply an aesthetic expressing no especially substantive social or political statement. Indeed, Hot Topic reduces fringe symbolism to a hollow style: pre-distressed shirts featuring the likes of Black Sabbath, David Bowie, or Joy Division evoke a historical fringe; pre-shredded jeans labor to conceal their wearer’s bourgeois status; and Batman earbuds invoke all the style and none of the pathos of the Caped Crusader.

Yet Hot Topic is far from the only company to charge into Doctor Who marketing. The founder of Her Universe—“a place for fangirls to step into the spotlight and be heard, recognized and rewarded”–told the Today show that Who merchandise was selling briskly, admitting that “`I never thought I would see it grow this much. … Girls would come up to me saying they wanted ‘Doctor Who’ shirts and I didn’t know how I could make it work logistically with the BBC in London.” But she was approached by BBC Worldwide’s own aggressive marketers because, according to their Director, “`She has a pulse on this demographic and on knowing what girls want.’”

The flood of Doctor Who merchandise reaching from toys to t-shirts to aquarium Daleks may indeed confirm that Doctor Who has been reduced to an aesthetic targeted to a particular consumer “demographic.” Doctor Who looms in this picture as an ambiguous symbol of aesthetic distinction; in contrast, geeks embrace something symbolically esoteric that is outside the mainstream. For some nervous fans, the passion they feel for Doctor Who or any other geek symbol hazards appearing irrelevant in the face of marketers’ dedication to profit.

However, it may be exactly the opposite: that is, perhaps the geek has now become valued by marketers precisely because geeks identify those social and stylistic niches into which people invest deep feelings. This no longer frames the geek as a unique entity, a stereotypically obsessive fan without connections to broader popular cultural discourses or politics. In an essay in Guerrilla Geek, Rory Purcell-Hewitt argues for something he dubs a “post-geek” that is quite along these lines. This post-geek is an assertively hybrid identity that does not fix geeks’ position within a particular subcultural niche: “the post-geek is one who has stepped beyond the barriers of the geek subculture, openly embracing philosophies and aesthetics from a multitude of cultures.” Contemporary geeks do indeed routinely poach on a rich range of popular cultural symbols—simply survey the cross-fertilization of symbols in Doctor Who shirts such as “Doctor Pooh,” “Gallifrey Road,” or “Doctor’s Eleven” that cannibalize other popular cultural geekery. That symbolic hybridity includes fans’ (and marketers’) conscious references to the show’s historical canon: Doctor Who evokes a half-century of programming and a distinctive retro aesthetic that the BBC’s avalanche of Doctor Who merchandise and DVDs routinely links to the newest episodes and storylines. This hybridity may be the geek’s elimination of their own uniqueness; that is, geeks and other subcultures are no longer isolated entities but wired hybrids thieving style and meaning from a range of discourses.

Doctor Who’s ascent to mass popularity certainly was fueled by the collapse of once-formidable barriers to Doctor Who access: much of Doctor Who’s run came in the context of a pre-cable TV world, the absence of mass-produced VHS tapes or VHS players, divides between the UK and US programming, and fandom organized around communities communicating through local clubs, modest conventions, and fanzines. Today, in contrast, a vast range of programming and linked marketing are accessible to nearly anybody with computer and/or cable access; BBC is systematically releasing every shred of Doctor Who programming on DVDs alongside branded books, audiobooks, and magazines; Who fans gather at massive conventions like Chicago TARDIS, Lords of Time (Australia), Regenerations (Swansea), and the official convention in Cardiff; fan communities are exceptionally well-connected online in sites like Gallifrey Base; and an enormous volume of online retailers specialize in commodities that are somehow cast as “geek.”

Subultures are not resisting any clearly defined mainstream, because normative social and stylistic codes are simply too dynamic and reside in ideology more than practice. Many geeks, though, hold onto the caricature of a normative mainstream to rationalize zealously guarding their unique identities, castigating newcomers as poseurs and warily patrolling the boundaries of the authentic canon. Perhaps the flood of Doctor Who DIY-er goods are the vanguard of material authenticity, or seeing the original Doctor Who late at night on a fuzzy black-and-white TV grants some fans some experiential privileges. But there was of course never a moment of “authenticity” untouched by the media, since Who fandom is based on a mass media product. Contemporary consumer culture is perhaps no longer populated by distinct collectives crafting individual styles in isolation; rather, we live in a world of heterogeneous styles in which appearances of resistance, deviance, and rebellion are simply a fashion. Geeks may be the preeminent creative spirits in such a moment, distinctive for their capacity to find the symbolically rich niches in mass culture like superheroes, Battlestar Galactica, and Doctor Who.

Piers D. Britton and Simon J. Barker

2003 Reading Between Designs: Design and the Generation of Meaning in The Avengers, The Prisoner, and Doctor Who. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Dick Hebdige

1979 Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Methuen, New York.

Matt Hills

2010 Triumph of a Time Lord: Regenerating Doctor Who in the Twenty-First Century. I.B. Tauris, London.

David Layton

2012 Humanism of Doctor Who: A Critical Study in Science Fiction and Philosophy. McFarland

Jefferson, North Carolina.

David Muggleton

2000 Inside Subculture: The Postmodern Meaning of Style. Berg, New York.

Steve Redhead, Derek Wynne, Justin O’Connor (eds.)

1998 The Clubcultures Reader: Readings in Popular Cultural Studies. Blackwell, New York.

John Tulloch and Henry Jenkins (eds)

1995 Science Fiction Audiences : Doctor Who, Star Trek, and Their Fans. Routledge, New York.

Peter Wright

2011 Expatriate! Expatriate!: Doctor Who: The Movie and Commercial Exploitation of a Multiple Text. In British Science Fiction Film and Television: Critical Essays, eds. Tobias Hochscherf, James Leggott, and Donald E. Palumbo, pp. 128-142. McFarland and Company, Jefferson, North Carolina.