Racing Along the Color Line

A July 31, 1926 advertisement in the Indianapolis Recorder for the third running of the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes.

This month the massive crowds at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway appear to confirm its confident claim to being the “motor racing capital of the world.” Racing began on the oval in 1909 and the 500-mile race first ran two years later, with the 99th running of the 500-mile race approaching on Memorial Day weekend. The speedway is a National Historic Landmark, and its fascinating social history reaches well beyond the obsessive statistics and biographical minutia that motorheads have compulsively detailed for a century. The IMS dominates American racing mythology and is as much a pilgrimage destination as a race track. Like so many shrines it invokes a host of American traditions that are perhaps more firmly rooted in our imagination and hagiography than especially concrete history.

The imagination of the speedway’s history has recently begun to contemplate historical racial inequalities in sports. This year the 500 Festival parade before the race will be marshalled by the 1955 state high school basketball champions from Indianapolis’ segregated Crispus Attucks High School. The Attucks champions’ place in the pre-race parade celebrates Indiana’s two most adored sports, basketball and racing, but of course the implications of sport and the color line extend beyond the hardwood and the speedway. No 20th-century Indiana institution escaped anti-Black racism, and the speedway and the Indianapolis 500 was long a segregated space and has included very few people of color on the track or in the pits. The prominence of the Attucks players makes a modest but potentially important concession of racism in sports, though the concrete social effects of such discussions remain to be evaluated.

In 1911 Henry Ford (left) posed with IMS founders (from left) Arthur Newby, Frank Wheeler, Carl Fisher, and James Allison (image Indianapolis Motor Speedway collection, IUPUI).

Speedway, the city where the IMS is located, was established in 1912 by Carl Fisher, James Allison, Arthur Newby, and Frank Wheeler, who had founded the track a few years earlier. Their new city supporting the track and local auto factories expressly forbade African-American residents. Fisher placed similar racial covenants on his development in Miami Beach, which he transformed from sparse oceanfront into one of the most prominent early 20th-century resorts. Fisher incorporated Miami Beach in 1915, barring Blacks from the beach and requiring all property owners to be WASPs.

Indiana proved to be especially receptive to such xenophobic sentiments, and much of the state’s historical narrative fixates on the Klan’s 1920’s influence; however, that attention to the hooded order often evades the persistence of Hoosier ethnocentrism long after the Klan’s political collapse, and it typically ignores how unspoken segregation shaped places like the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In 1910, for instance, African-American boxer and motor racing fan Jack Johnson hoped to stage an exhibition race at the speedway, but in August, 1910 Louis Chevrolet zealously defended the speedway’s segregation. Chevrolet, who drove in the 500 four times and eventually founded the Chevrolet Motor Car Company, argued that “there are no negro automobile-race drivers at the present time, and if I understand correctly there is a ban against it. I am not willing to allow my name to be used in the same programme as that of Jack Johnson, and if the Indianapolis Motor Speedway management cannot confine itself to automobile racing without bringing a negro barn-storming pugilist, I believe it is time for the white drivers to quit the game on that track.” Undeterred, Johnson raced Barney Oldfield in October at the Sheepshead Bay Track in New York (with Oldfield winning). The American Automobile Association registered its disapproval of the exhibition and suspended Oldfield for a series of such unsanctioned races (he was eventually reinstated and raced in the 1914 and 1916 versions of the Indianapolis 500).

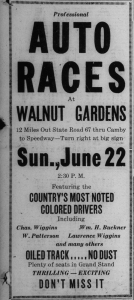

Segregation ironically provided entrepreneurial possibilities for business people who recognized the potential profits of Black racing fans. In 1924 William Rucker formed an organization initially known as the Colored Speedway Association, and in his role as President Rucker came to be known simply as “Pres.” Indiana Avenue entrepreneur Harry Dunnington and lawyer Robert Brokenburr joined the cause, and for financing support Rucker turned to two White partners, Oscar Shilling and Harry Earl. Rucker moved to Indianapolis from Nashville in about 1920, and when he arrived in Indianapolis he worked in railroad shops where he met Shilling, who was a mechanical engineer. Earl was a machine shop foreman who eventually promoted races at Walnut Gardens Speedway, a one-mile dirt oval in Camby, which was in operation by the mid-1920s.

Segregated Black leisure flourished in the 1920s. Negro baseball leagues, for instance, were as old as the game itself, but they experienced significant growth at the same moment as segregated racing. The Negro National League was established in 1920 and counted the Indianapolis ABC’s amongst its eight initial teams. The league’s first game was played at Washington Park between the ABC’s and the Chicago American Giants in May, 1920. In the 1924 Colored Speedway Association race, the American Giants’ manager Rube Foster fielded a car driven by the American Giants’ mechanic William Walthall.

The Colored Speedway Association’s first race in August, 1924 was won by Malcolm Hannon of Indianapolis, with only three cars surviving to the end. Jack Johnson presented a trophy to Hannon. The 100-mile race began to be referred to as the “Gold and Glory” race after the Chicago Defender’s Frank Young wrote in 1924 that “this auto race will be recognized throughout the length and breadth of the land as the single greatest sports event to be staged annually by colored people. Soon, chocolate jockeys will mount their gas-snorting, rubber-shod Speedway monsters as they race at death defying speeds. The largest purses will be posted here, and the greatest array of driving talent will be in attendance in hopes of winning gold for themselves and glory for their Race.”

In 1929 the race was run for its sixth consecutive year, with Barney Anderson of Detroit winning the race.

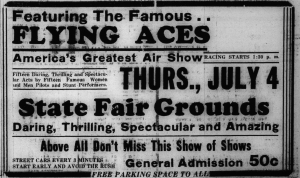

The Indianapolis 500 staked a claim to patriotism by holding its race on Memorial Day weekend. The first 1924 race sponsored by the Colored Speedway Association came on Emancipation Day weekend, but beginning in 1927 the 100-Mile Sweepstakes invoked its own nationalist ideology by holding its race on July 4th. In 1930 The Indianapolis Recorder paralleled the Indy 500 and the 100-Mile Sweepstakes when it observed that “At this season of the year the magnetic odor of burning castor oil and scorching rubber attracts many thousands and more to Indianapolis, the `Crossroads of America,’ to witness two annual auto classics, the Memorial day race and the Independence Day race on July 4th, the one in which we are particularly interested, because it is our own, staged by our own officials, drove by our own drivers, and a game lot they are, taking daredevil chances to win fame and money.”

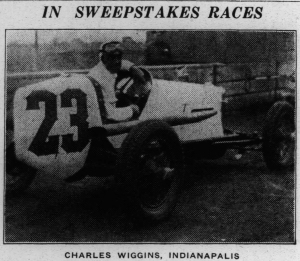

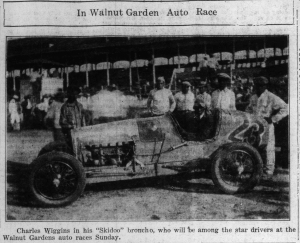

In 1925, 1926, and 1927, Indianapolis drivers won the race. Lee Robert “Bobby” Wallace took the 1925 running of the race; Charlie Wiggins won a year later (he also claimed the crown in 1931, 1932, and 1933); and Bill James won in 1927. All of these drivers appeared in races throughout the Midwest into the mid-1930’s. Chicago driver and bail bondsman “Wild Bill” Jeffries claimed the 1928 victory. Police officers arrived before the race and threatened to seize Jeffries’ car if he did not pay $300 they claimed he owed to the Chevrolet brothers for their Frontenac, and Jeffries provided a diamond ring that was returned after winning the purse. Detroit’s Barney Anderson claimed the 1929 race, a race in which local driver Edward Grice became the only driver to ever die in the Gold and Glory sweepstakes. The race was held 11 times, with its last race coming in 1936.

Three-time winner Charlie Wiggins was perhaps the most famous African-American driver, and Todd Gould’s 2002 For Gold and Glory: Charlie Wiggins and the African-American Racing Car Circuit provides a thorough study of Wiggins and inter-war African-American racing. Born in Evansville, Indiana in July, 1897, Charlie Wiggins was living in Earlington, Kentucky (immediately south of Evansville and the Indiana state line) in 1900 with his father, coal miner Sport Wiggins, mother Jennie Baker Wiggins, and brother Lawrence, who would become a successful driver in his own right. A decade later the census-keeper found Sport, Charley, and Lawrence in Evansville with two new brothers, but Jennie died in 1906.

When Charlie Wiggins registered for the draft on August 24, 1918, he was living in Evansville and recorded his employer as “Benninghoff and Nolan,” a garage run by Henry Benninghoff and Eugene Nolan. Wiggins first appeared in Indianapolis’ city directory in 1921, when he and wife Roberta were living at 617 North West Street, and he appeared in the directory as a mechanic. The Wiggins moved a year later to 1012 North West, and by then he was working in a garage on West Merrill Street (near the present location of Lucas Oil Stadium), which he purchased from owner Louis Sagalowsky in 1924.

A 1937 aerial view of the dirt track that sat just east of Allisonville Road (left side of this image).

African-American racing flourished in the segregated Midwest into the Depression. For instance, a Chicago Colored Speedway Association was founded by Bill Jeffries not long after William Rucker’s Indianapolis Colored Speedway Association. In late 1927 Rucker’s Colored Speedway Association became known as the Indianapolis Colored Automobile Racing Association (and Rucker retired in 1929). While the July 4th race was held at the Indiana State Fairgrounds most years, races also were run at Harry Earl’s Walnut Garden Speedway in Camby (the 1931 and 1933 Gold and Glory races were held there), and a converted dog-racing track at 4900 Allisonville Road held at least one race in August, 1935.

An Ohio promotion team sponsored the 1935 race at the Fairgrounds, and they staged an airshow to precede the race. Roughly 3000 people attended at .50 cents each, but as the race was about to begin it became clear that the promoters had left with the gate proceeds and the purse. The Recorder said nearly nothing about the scam, noting only that the races were cancelled because of rain and “last minute details.”

In 1936 supporters hoped that the September running of the Gold and Glory race would restore the event’s prestige, and in a planning meeting Freeman Ransom told the executive committee that “Colored drivers could and should be allowed opportunity to display their skill and courage … A broad aim envisions colored drivers in the 500-mile classic.” An elite field was recruited, and prior to the race Indiana Democrats staged a political rally followed by a rain delay. Because a curfew was approaching, the dirt track was not watered and oiled down after the rain. The resulting dusty conditions left drivers with nearly no vision of the track, and a massive crash on the second lap left “cars melted into a mountain of rending, distorted metal and buried men.” Charlie Wiggins received the worst injuries in the crash, and his right leg was amputated following the 13-car accident. The injury was the end of Wiggins’ racing career, though he continued working for another four decades before his death in 1979. Bobby Wallace received a serious injury in the same mass accident, and after surgery for a skull fracture his career ended as well (he died three years later). The loss of the stars and financial pressures of managing the league had finally caught up to its backers, and the Gold and Glory race ended soon after with the bankruptcy of the Colored Speedway Association.

In October, 1947 White sports writer W. Blaine Patton approached Speedway officials “to find out if Negro race drivers were outlawed by the American Automobile Association.” The Indianapolis Recorder repeated Patton’s lament that “the greatest automobile race in the world is the annual 500 mile international gasoline classic derby held on May 30 each year at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. . . . A Negro has never shared in this legacy of gold.” Officials acknowledged to Patton that there was “no rule against the race” participating in AAA sanctioned races, which Patton recognized may have exposed a “`gentleman’s (?) agreement’” against the participation of Black drivers (as opposed to a formal code). The AAA’s contest board President suggested as much when he acknowledged that “there has never before been anytime that the A.A.A. has ever barred any contestant by reason of race, creed or any other cause.”

A week later the Indianapolis Recorder reported that Wiggins and Sumner “Red” Oliver (who finished second in the final running of the Gold and Glory race) intended to attempt to qualify a car for the Indianapolis 500. The two men attempted to enter a car at the Dayton Speedway but were rebuffed “because they were not registered with the AAA. The officials said, however, that the men could register and participate in 3-A dirt track races next summer.” African-American driver and mechanic Mel Leighton did secure a license in 1948, but he never raced at Indianapolis.

Few Black drivers or teams would ever follow the Gold and Glory drivers. In 1968 The Indianapolis Recorder’s Andrew Ramsey concluded that the Indianapolis 500 “has been safely white from its beginning in 1911.” He argued that “All Negroes hereabout and most of the white citizens are quite aware of the fact that the Indy 500 Mile Auto Race, the greatest spectacle in automotive racing is along with the Kentucky Derby, one of the last bastions of lily-white sportsmanship.” Ramsey singled out the Indianapolis 500 Festival Parade as one of the most prominent mechanisms the Speedway and city used to present the “racial identification” of the 500 and the city itself. Ramsey pointed to the universally White “500 Festival Princesses” (compare this year’s edition) and dryly concluded that “somewhere in Indianapolis there might be a Negro who was surprised not to see a Negro girl pictured among those vieing [sic] for the honor of being elected as the 1968 `500’ Festival Queen, but it is doubtful.” Ramsey’s attack on the race was not simply a rejection of the track as a White space; rather, Ramsey concluded that it “is of very little use to protest the lily-white character of the `500’ Festival committee and leave alone the giant automobile complex which is basically racist. The festival is perhaps denying Negroes the privilege of being prominently shown while the industry itself is denying him the right to work.”

Few Black drivers or teams would ever follow the Gold and Glory drivers. In 1968 The Indianapolis Recorder’s Andrew Ramsey concluded that the Indianapolis 500 “has been safely white from its beginning in 1911.” He argued that “All Negroes hereabout and most of the white citizens are quite aware of the fact that the Indy 500 Mile Auto Race, the greatest spectacle in automotive racing is along with the Kentucky Derby, one of the last bastions of lily-white sportsmanship.” Ramsey singled out the Indianapolis 500 Festival Parade as one of the most prominent mechanisms the Speedway and city used to present the “racial identification” of the 500 and the city itself. Ramsey pointed to the universally White “500 Festival Princesses” (compare this year’s edition) and dryly concluded that “somewhere in Indianapolis there might be a Negro who was surprised not to see a Negro girl pictured among those vieing [sic] for the honor of being elected as the 1968 `500’ Festival Queen, but it is doubtful.” Ramsey’s attack on the race was not simply a rejection of the track as a White space; rather, Ramsey concluded that it “is of very little use to protest the lily-white character of the `500’ Festival committee and leave alone the giant automobile complex which is basically racist. The festival is perhaps denying Negroes the privilege of being prominently shown while the industry itself is denying him the right to work.”

Ramsey sarcastically noted that “of course with the Indianapolis 500 Festival there are some Negroes in the parade because it is difficult to sweep all the city’s Negroes under the rug before the visitors come trouping into the city, but Negroes have very little to do with the operation of anything connected with the operation of any 500 activity.” He suggested that many visitors “are surprised to learn that there are Negroes living in Indianapolis, since none has ever been pictured in connection with the super spectacle.”

Nearly a half-century after Ramsey’s lament, the 1955 Crispus Attucks basketball team prepares to lead the same parade Ramsey once attacked. There is of course some genuine reconciliatory potential to acknowledging the Attucks team’s victory in the face of stiff anti-Black resistance and recognizing the importance of sport in our collective racist heritage. The challenge is to see how sport’s intersection with the color line reaches well beyond basketball courts and race tracks and eventually requires something more substantial than good feelings alone.

Sources

Todd Gould

2002 For Gold and Glory: Charlie Wiggins and the African-American Racing Car Circuit. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Rick Knott

2005 The Jack Johnson V. Barney Oldfield Match Race of 1910; What It Says about Race in America. Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 29(1):39. (subscription access)

Charles Leerhsen

2011 Blood and Smoke: A True Tale of Mystery, Mayhem and the Birth of the Indy 500. Simon and Schuster, New York.

Leonard J. Moore

1991 Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Richard B. Pierce

2005 Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Jean Williams

2012 The Indianapolis 500: Making the Pilgrimage to the “Yard of Bricks.” In Sport, History, and Heritage: Studies in Public Representation, eds. Jeffrey Hill, Kevin Moore, and Jason Wood, pp.247-262. Boydell Press, Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Image

1911 Henry Ford and founders image from Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection

Posted on May 16, 2015, in Uncategorized and tagged #WPLongform, Charlie Wiggins, Gold and Glory, Indianapolis 500, Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Bookmark the permalink. 2 Comments.

Seriously, Paul, great job! How you managed to research and write this while dealing with this P&T stuff, I will never know!

*******************************

Eric L. Hamilton

Department of Anthropology

[sig logo]

Reblogged this on Lily Does Archaeology.