Memory, Monuments, and Confederate Things: Contesting the 21st-Century Confederacy

Phoenix’s 1961 Memorial to Arizona Confederate Troops (click for larger image, from Visitor7/wikimedia).

In 1961 the United Daughters of the Confederacy presented Phoenix, Arizona with a memorial dedicated to Arizona’s Confederate soldiers. The “Memorial to Arizona Confederate Troops” is a copper ore stonework shaped in the state’s outline that rests atop a pedestal graced by petrified wood. The monument sits on a plaza alongside 29 other memorials at the Arizona State Capitol that range from war memorials to a Ten Commandments monument. The Phoenix Confederate memorial is far removed from the heart of Civil War battlefields and Southern centers, but it is now part of a nationwide debate over the contemporary social and political consequence of Confederate things.

The earliest Confederate monuments were located in cemeteries and included this 1869 90-foot high memorial to the 18,000 Confederates buried in Richmond, Virginia’s Hollywood Cemetery (author’s image).

In the pantheon of Confederate things, statuary is perhaps somewhat distinct from the flags, license plates, and assorted collectibles emblazoned with Confederate symbols. Statues and memorials aspire to make timeless sociohistorical statements and define or create memory, capturing idealized or distorted visions of the war that say as much about their makers and viewers as their subject. Yet as time passes monuments routinely begin to appear aesthetically dated or even reactionary. Viewed from the vantage point of the early 21st century, many Confederate monuments are simply documents of 150 years of shallow fantasies of the South and the Confederacy. Some of those public monuments can possibly foster counter-intuitively reflective and sober discussions about the Civil War, which is a century-and-a-half heritage rather than an objective historical event. However, such discussions risk being circumvented by contemporary Confederate defenders who distort the Confederacy’s history and studiously ignore why an imagined Confederate heritage has become so appealing—if not unsettling–well outside the South.

While it rarely appears in standard Civil War narratives, Arizona can claim a genuine Civil War history. Swaths of southern Arizona and New Mexico territories were claimed by the Confederacy a century before the monument was erected in Phoenix. A secession convention agreed to leave the Union and become the Arizona Republic in 1861, and in February 1862 it became recognized by the Confederacy as the Confederate Territory of Arizona. Confederates fought under the Arizona banner through the war, but the Governor of the Confederate territory retreated to Texas in July, 1862, and for most of the war the military presence in the region was by Union forces.

Dedicated in September, 1867, this Romney, West Virginia monument was one of the nation’s first Confederate memorials (Justin A. Wilcox/wikimedia).

The vanquished Confederacy began to memorialize its cause almost instantly. The town of Cheraw, South Carolina claims to have erected the first Confederate memorial, a cemetery marker erected in June, 1867 (while the town was still occupied by Union forces); a Confederate memorial was dedicated in September, 1867 in Romney, West Virginia. These earliest monuments to the Lost Cause were nearly all cemetery memorials, but the South began busily erecting public monuments to the Confederacy in the late-19th and early 20th-centuries. Scores of statues were placed in former Confederate towns, mostly by a host of ladies’ memorial associations who assumed the care for the Civil War dead and would become the leading proponents of Lost Cause ideology. From its first issues in 1893, Confederate Veteran zealously tracked such monument construction efforts (for example, compare their 1893 monument inventory), and by 1914 they gushed that roughly a thousand public monuments dotted the South: “Year by year with increasing rather than decreasing devotion all over the Southland monuments are rapidly being erected to the heroes who died in the effort of the Confederate States to win a national life.”

In 1908 the United Daughters of the Confederacy dedicated this anonymous soldier monument in Bentonville, Arkansas, later adding a plaque honoring Confederate James Henderson Berry (wikigringo/wikimedia).

These monuments were being constructed as the war was entering into the realm of “postmemory”; that is, it was “remembered” by a generation who actually had no firsthand experience of the war but was nonetheless traumatized by its effects and the testimony of those who had lived through it (a notion developed to interpret Holocaust memory). That generation was eager to rebuild the South and claim a common White heritage. As memorialization reached beyond the confines of cemeteries, one of the most prominent unifying symbols of the White South and North alike was the statue of an anonymous foot soldier patrolling the early 20th century courthouse lawn. In the final quarter of the 19th century Kirk Savage argues that the everyday White soldier underscored community service to the competing national causes while underscoring that citizenship was restricted to Whites.

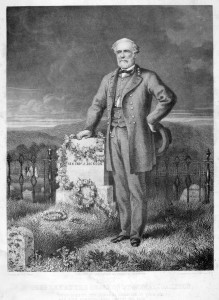

The most famous rebels found prominent places in Southern cities, where they became symbols of a moral cause rather than a vanquished nation. No figure was more celebrated than Robert E. Lee, who was commemorated in a host of Southern cities including a New Orleans monument in 1884. In 1876 planning began for perhaps the most famous Lee monument, a Richmond, Virginia statue on Monument Avenue that was completed in 1890. Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart followed Lee to Monument Avenue in 1907, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was installed a month later, and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson joined them in 1919 (eventually Confederate naval officer Matthew Fontaine Maury was included in 1929 and a statue of African-American tennis player and activist Arthur Ashe was erected in 1996). The memorial landscape extended far beyond statues alone: for instance, in the early 20th-century a host of roadways also were renamed for Confederate heroes, of which the 4000-mile long Jefferson-Davis Highway system is perhaps best known (PDF).

All of these places became scenes of pilgrimage and ritual. For instance, perhaps the most hallowed of all Confederates was Lee, whose grave in Lexington, Virginia rapidly became a place to mourn the Confederacy. In 1896 the Charlotte Observer noted that a local woman “brought with her from Lexington some ivy from Gen. Lee’s grave, which she has planted on the west side of the First Presbyterian Church. … It will be doubly sacred to the people of the First church from its association with the great Southern leader.” That same year a Robert E. Lee grave ivy planted at Yale was stolen (a planting that had been resisted by some students and faculty), leading one newspaper to argue that the University did not “need to blush for her romantic memorial of one of the noblest Americans—even if a Confederate leader—who ever lived” (a new Lee ivy was planted a year later). In 1908 Mississippi’s Jackson Daily News was among a series of American newspapers reporting that a tablet had been placed in Amoy (now Xiamen) China at the scene of “a slip of ivy from Gen. Lee’s grave” that had been planted there 10 years earlier. Lexington also was the home to the grave of Stonewall Jackson, whose grave has likewise long been the scene of pilgrimage. In 1886 the Indiana State Sentinel reported that the Bishop of the Southern Methodists was presiding over its conference with a “gavel made of wood from the tree that grows by `Stonewall’ Jackson’s grave at Lexington, Va. The roots of the tree embrace the coffin.”

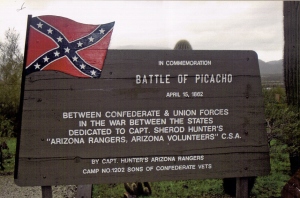

A marker at the Battle of Picacho site erected by the Sons of Confederate Veterans (image Marine 69-71/wikimedia)

Arizona had a short secessionist history and could lay claim to Confederate heritage, but the state made no contribution to the turn-of-the century Confederate monument boom. William Stoutamire’s 2010 study of Arizona’s Civil War heritage indicates that the state’s first Civil War monument was not erected until 1928, and it memorialized three California Cavalry soldiers killed in 1862. In April 1862 Confederate rangers engaged Union cavalry at Picacho Peak and killed three Union soldiers in the war’s westernmost military confrontation (compare coverage from The Petaluma Argus). Yet the Confederate foray into Arizona was a history that remained largely un-commemorated for most of the century following the war’s end.

Confederate sympathies swelled in the South after World War II, buoyed by White anxieties over the Civil Rights movement. The postwar affection for a romanticized Confederate history would extend its reach into Arizona, where one of the most prominent national opponents of civil rights reforms was Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater. In August 1950 a group met in Tucson to consider forming a chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and they indicated they were contemplating the construction of a Confederate monument at Picacho. In 1951 reenactors dressed as the Arizona Rangers marched in the Tucson Rodeo Parade (and the Sons of Confederate Veterans continue to participate in the annual event). In 1958 the Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp 1202 erected a memorial to the Confederate rangers who fought in the “War Between the States” battle at Picacho. Four years later during year-long Centennial celebrations 5000 people gathered for a reenactment of the Battle of Picacho Pass.

In the wake of the Civil War Centennial, some of the Confederate fervor declined, and by 1972 the 1928 monument had fallen into disrepair. However, by the early 1980s a neo-Confederate movement began to redefine the Lost Cause. In 1984 the United Daughters of the Confederacy, their auxiliary Children of the Confederacy (for children from birth to 18), and the Arizona Historical Commission added a new plaque to the 1928 Picacho monument that signaled a quite different tone than the original marker. The 1984 marker was “dedicated to the Confederate frontiersmen who occupied Arizona territory CSA created by Jefferson Davis, February 4, 1862.” The plaque suggests that 10 “Confederate cavalrymen successfully defended Picacho Pass,” repeating a familiar theme in pro-Confederate narratives that heroicize the rebels’ noble fight against overwhelming force; the plaque sounds that tired mantra in its celebration of the handful of rebels who “delayed for a month the advance of a 2300-man Union column and hastened establishment of Arizona territory U.S.A. on February 24, 1863.”

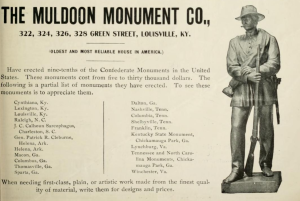

In 1900 a sufficient number of monuments were being erected that Confederate Veteran included this advertisement for Louisville, Kentucky’s Muldoon Monument Company.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy formed in 1894 and has remained among the most active proponents of memorial construction, pro-Southern histories, and textbook “accuracy” that remain at the heart of neo-Confederate movements. Mildred Lewis Rutherford, for instance, was Historian of the United Daughters of the Confederacy as well as the Confederated Southern Memorial Association, which formed in 1900 to unite a vast number of ladies’ memorial associations in the vanquished Confederacy. The prolific Rutherford penned a series of popular histories that selectively borrowed from or grossly misrepresented primary documents, but the themes she championed remain enormously attractive to many contemporary ideologues. Rutherford argued that the Constitution was a compact between sovereign states; consequently, the Confederacy’s secession did not constitute a rebellion, a theme often featured in neo-Confederate histories painting Lincoln and a circle of Northerners as coercive warmongers (compare this 1920 Confederate Veteran article). Much like a century of Confederate apologists, Rutherford’s imagined war was not fought over slavery at all, and she painted an abhorrent picture of placid and well-treated captives.

This 1920 passage from a Mildred Lewis Rutherford study outlined some of her rules for assessing historical textbooks on the Confederacy.

All of this fueled Rutherford’s zealous lobbying for revised textbooks, which she argued should not refer to the war as rebellion, suggest it was fought for slavery, indicate slaveholders were cruel or unjust, or glorify Lincoln while villifying Jefferson Davis. A textbook committee under Rutherford’s direction vigorously patrolled school books and reported on those textbooks that did not equitably represent the South. In 1921 Rutherford published one of the most jarring revisionist histories, a school pamphlet called The Truth of the War Conspiracy of 1861. Huger William Johnstone’s 52-page tract boldly laid the responsibility for the Civil War at the feet of Abraham Lincoln and a complicated conspiracy to start the war. In 1922 the United Confederate Veterans unanimously endorsed the report, “which proves the Confederate War was deliberately and personally conceived and its inauguration made by Abraham Lincoln.” While such conspiracy theory histories dramatically distorted the war, Rutherford’s books are still in print, and her defense of Southern “home rule,” antebellum life, and natural social, racial, and gendered hierarchies remain emotionally powerful for many audiences a century later.

The Phoenix monument was erected in the midst of a backlash to integration that witnessed a similar embrace of reactionary Confederate history in many other communities. Despite memorial-makers’ best efforts to cast their messages as timeless, though, it is impossible to separate memorials’ 21st-century reception from contemporary experience. While Phoenix contemplates the local meaning of Confederate things on the public landscape, other communities have removed or seriously contemplated removing such monuments.

New Orleans’ Robert E. Lee Monument was erected in February, 1884, becoming part of an especially rich Confederate landscape. Some of the contention over these memorials was prosaic: In 1953, for instance, there was public outcry when a sign was hung at the statue during maintenance indicating it was under “reconstruction,” which was hastily changed to “rebuilding.” However, more consequential tensions were often played out in the shadow of General Lee. In January, 1972, for instance, a memorial parade marking Lee’s birthday laid a Confederate flag at the foot of the Lee monument and included in the parade Klansman Addison Roswell Thompson. Between 1954 and 1975 Thompson ran 14 unsuccessful campaigns for New Orleans Mayor or Louisiana Governor on an unabashedly White supremacist platform. During his 1966 gubernatorial campaign, for instance, Thompson indicated he stood for “`states rights, free enterprise, racial segregation, individual freedom and keeping government out of businesses that can be handled by private enterprise,’” and punctuating it by adding that “`We must stop race mixing.’” In 1974 Thompson celebrated the Klan as “a terrorist organization. … All our violence is secret, but we’re violent, take my word for it.’” The 1972 Lee birthday march ended with two African Americans arrested for attacking Thompson. Among the White supporters in the Lee parade was David Duke, a Louisiana State University student and Klansman who would go on to serve in the State House of Representatives and run several well-publicized albeit unsuccessful campaigns for Governor, the US Senate, and President.

In December, 2015 the New Orleans City Council voted to remove four memorials associated with the city’s Confederate landscape. The most unsavory of the four monuments was erected in 1890 to commemorate what was long referred to as the “Battle of Liberty Place.” Over several days beginning on September 14, 1874 between 3500 and 5000 White League rioters led an insurrection against the Reconstruction government after a Republican victory (including an African-American Lieutenant Governor). Numerous Confederate veterans were in the White League’s ranks (about 44% were former Confederates), but 30% of its number were born after 1850 and had come to their anti-Reconstruction racism beyond the battlefield. The rioters occupied the State House and killed about 100 police and state militia in an especially violent effort to restore antebellum order. Formed in 1874, the White League was the paramilitary arm of the Democratic party, and their platform acknowledged that their goals included the “maintenance of our hereditary civilization and Christianity menaced by a stupid Africanization.” The White League violently prevented Republican political organization and intimidated or murdered African Americans and Republican voters.

The Fourteenth of September Memorial Association was formed in 1886 to honor the White League’s dead. When the monument was dedicated in September, 1891 The Times-Democrat indicated that the memorial had been “erected to those who lost their lives in the act of disenfranchisement from alien and negro rule.” A copper box of artifacts was placed in the cornerstone that included a “map of the Battle of New Orleans for Freedom, Sept. 14 1874” and the bullet that killed rioter Charles Brulard. During anniversaries of the Liberty Place riot now-familiar themes of local sovereignty, home rule, and martyrdom by common men were regularly invoked. On the first anniversary of the monument’s erection, The Times Picayune rhapsodized that the riot was “when home rule and self-government were reborn in the metropolis of the South.” During the 1895 annual memorial, The Times Picayune celebrated “the names of the martyrs whose names are immortalized in the granite tablet,” noting that “twenty-one years has passed since the freedom of Louisiana was achieved in fire and blood.” In 1963 the riot was still being hailed as having brought “the end of Reconstruction to the South, and started the Southern people on their way to the great prosperity which they know now.”

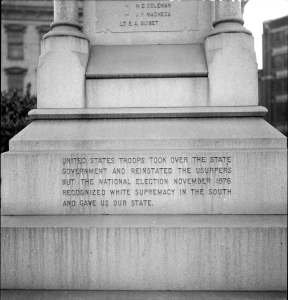

When Dorothea Lange took this picture of the Liberty Place monument in 1936, she called it a “monument erected to race prejudice” (Library of Congress)

Few Confederate monuments have been modified as many times as the Liberty Place monument, which was also moved twice. In 1932, a new inscription was added to the monument that applauded the end of Reconstruction, indicating that “the national election of November 1876 recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state.” In the wake of World War II Liberty Place became a common backdrop for White supremacists’ public rallies. In 1974 a plaque was added to the monument to soften its expression of racist violence, admitting that “the sentiments in favor of White supremacy expressed hereon are contrary to the philosophy and beliefs of present-day New Orleans.” Nevertheless, in 1976 protestors lobbied for the removal of the monument when the Klan planned a march to the monument, which it proudly considered a key moment in White supremacists’ history. In 1981 the Mayor proposed putting the monument in storage, and the City Council approved a resolution to remove the post-1891 inscriptions on the monument. In 1989 the monument was removed during a road construction project, and it was replaced in 1993 with the added inscription “In honor of those Americans on both sides who died in the Battle of Liberty Place … A conflict of the past that should teach us lessons for the future.”

In April 2017 the Liberty Place monument was the first of the four Confederate monuments to be removed, and the remaining three Confederates were removed in May: the 1911 Jefferson Davis monument was dismantled May 11th ; the 1915 General P. G. T. Beauregard Statue came down on May 17th; and the 1884 Lee statue was removed May 19th. They now sit in an undisclosed location awaiting a plan for their potential museum display (a suggestion to move the Lee monument to Washington and Lee University was rejected by the University).

In 2004 the Jefferson Davis monument was spray-painted by protestors. Erected in 1911, it was removed in May, 2017 (Bart Everson/wikimedia)

On one hand, perhaps these monuments are “raw wounds” that compel us to confront the underside of American history in public space. Arizona’s own state historian Marshall Trimble suggested as much when he defended Arizona’s Confederate memorials against the fate of the New Orleans monuments: “`One thing that America should be proud of is that it’s never tried to expunge or hide its history. It’s: Let the world see its warts and all.’” Trimble paints monument removal as the erasure of history at the hands of unjust ideologues, descending to comparisons with authoritarians: “This is not Russia and it’s not Nazi Germany, this is America. We always show warts and all. And if we don’t show this—if we hide it, it gets eradicated and it’s like we’re changing our history.” On the other hand, neo-Confederates have had nearly nothing to say about those strategically unidentified sociohistorical “warts,” instead restricting most of their criticism of the Confederacy to critique of battlefield strategies. For defenders like Trimble, monuments are themselves inseparable from history itself, material and public confirmations of neo-Confederate fantasies. Yet every monument is instead an individual artifact with its own history capturing the imagination of its makers and audiences rather than an event or personage.

Many defenders including Trimble believe leaving such monuments in place encourages historical clarity and will foster reflective dialogue. Yet Dell Upton ridicules the notion that leaving the Liberty Place monument in place displays “progress,” suggesting that we might as well return “White” and “Black” signs to water fountains. Knowing a dark heritage is not the same as celebrating it publicly in monuments on behalf of the state. There seems little likelihood the Civil War will be “forgotten,” but the distorted neo-Confederate picture of the Civil War and the subsequent 150 years will indeed be transformed.

References

Jon D. Bohland

2013 Look Away, Look Away, Look Away to Lexington: Struggles over Neo-Confederate Nationalism, Memory, and Masculinity in a Small Virginia Town. Southeastern Geographer 53(3): 267-295. (subscription access)

Sarah H. Case

2002 The Historical Ideology of Mildred Lewis Rutherford: A Confederate Historian’s New South Creed. The Journal of Southern History 68(3): 599-628. (subscription access)

2009 Mildred Lewis Rutherford (1851–1928): The Redefinition of New South White Womanhood. In Georgia Women: Their Lives and Times, eds Ann Short Chirhart and Betty Wood, pp. 272-296. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

Confederated Southern Memorial Association

1904 History of the Confederated Memorial Associations of the South. Graham Press, New Orleans.

Euan Hague, Heidi Beirich, and Edward H. Sebesta, editors

2008 Neo-Confederacy: A Critical Introduction. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Euan Hague and Edward H. Sebesta

2011 The Jefferson Davis Highway: Contesting the Confederacy in the Pacific Northwest. Journal of American Studies 45(2): 281 – 301.

Marianne Hirsch

2012 The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. Columbia University Press, New York.

James K. Hogue

2006 Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battles and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction. LSU Press, Baton Rouge.

John Kendall

1922 History of New Orleans. The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago.

William B. Lees and Frederick P. Gaske

2014 Recalling Deeds Immortal: Florida Monuments to the Civil War. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Jonathan I. Leib

2004 Robert E. Lee, “Race,” Representation and Redevelopment along Richmond, Virginia’s Canal Walk. Southeastern Geographer 44(2): 236-262. (subscription access)

Andrew E. Masich

2012 The Civil War in Arizona: The Story of the California Volunteers, 1861–1865. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Justin A. Nystrom

2010 New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom. Johns Hopkins University press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Lawrence N. Powell

1999 Reinventing tradition: Liberty place, historical memory, and silk‐stocking vigilantism in New Orleans politics. Slavery and Abolition 20(1): 127-149. (subscription access)

Monica L. Rhodes

2012 Disorderly History: Cultural Landscapes, Racial Violence, and Memory, 1876-1923.

Masters Thesis. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Kirk Savage

1997 Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

William Stoutamire

2010 From North to South, Out West: Civil War Memory in Arizona. The Journal of Arizona History 51(3): 197-222. (subscription access)

Dell Upton

2015 What Can and Can’t be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

John J. Winberry

1983 “Lest We Forget”: The Confederate Monument and the Southern Townscape. Southeastern Geographer 23(2): 107-121.

Images

Battle of Picacho Marker image from Marine 69-71/wikimedia

Bentonville, Arkansas Confederate Memorial image from wikigringo/wikimedia

Confederate Veterans Monument Phoenix image from Visitor7 wikimedia commons

Jefferson Davis Monument image from Bart Everson/wikimedia

Lee at Jackson’s grave 1867 lithograph image from State Archives of North Carolina/wikimedia

Lee Monument New Orleans, circa 1900 image by George Francois Mugnier

Lee Monument New Orleans removal image from abdazizar.wikimedia

Liberty Place Monument 1912 image from Winter in New Orleans season 1912-1913.

Liberty Place 1936 Dorothea Lange image from Library of Congress

Liberty Place Monument 2010 image from Michael Begley/wikimedia

Romney West Virginia Confederate Memorial image from Justin A. Wilcox/wikimedia.

Posted on June 16, 2017, in Uncategorized and tagged #WPLongform, civil war, monuments, neo-Confederacy, New Orleans, Phoenix. Bookmark the permalink. 11 Comments.

Wow, this is an incredible piece–definitely a tour-de-force through archaeology, monuments, and with a wonderful concluding statement. I’ve used it for an update to my classnotes on the question of Is Nationalism Bad?

Thanks, the material really is fascinating–cool things, great primary documents, compelling contemporary heritage discourses, and some interesting regional and local wrinkles with implications for much bigger questions.

Nice work. Very interesting. Erasing historical monuments for sensitivity is a joke. Love the spineless new Americans (not)

Pingback: Losing the past or changing the future? Archaeologists and modern monuments • The Berkeley Blog

Pingback: Losing the Past or Changing the Future? Archaeologists and Modern Monuments - LA Progressive

Pingback: The Archaeology of Public Memory and Civic Identity

Pingback: Confederate Statues, Archaeology, and the Soul of Community | Intercultural Urbanism

Pingback: The Columbian Geography of Binghamton | MAPA

Pingback: On Monuments and Racial Violence | Anthropology-News

Pingback: On Monuments and Racial Violence – Medicine by Alexandros G. Sfakianakis,Anapafseos 5 Agios Nikolaos 72100 Crete Greece,00302841026182,00306932607174,alsfakia@gmail.com,

Pingback: The Distinction Between Racist Statuary and the Pyramids – Samuel Pfister