Blog Archives

The Prosaic Relics of Breaking Bad and Fan Culture

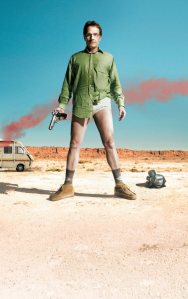

This week an anonymous bidder secured one of the most fascinating relics, a material thing evoking the distinctive power of a venerated figure: Walter White’s cotton briefs. The Breaking Bad anti-hero is a dark, vengeful character with whom we uncomfortably sympathize, so it might seem somewhat surprising that his underwear and many more series items are in demand. Yet Walter White is compelling because for many people his tale brazenly questions universal morals. In the desperate face of impending death, Walter White lives in a world in which good and bad ideals become clumsy and unsettling abstractions. Many of us are fascinated by the resolve of an individual acting with their own sense of honor and morality, even if his choices are often problematic if not evil.

This week an anonymous bidder secured one of the most fascinating relics, a material thing evoking the distinctive power of a venerated figure: Walter White’s cotton briefs. The Breaking Bad anti-hero is a dark, vengeful character with whom we uncomfortably sympathize, so it might seem somewhat surprising that his underwear and many more series items are in demand. Yet Walter White is compelling because for many people his tale brazenly questions universal morals. In the desperate face of impending death, Walter White lives in a world in which good and bad ideals become clumsy and unsettling abstractions. Many of us are fascinated by the resolve of an individual acting with their own sense of honor and morality, even if his choices are often problematic if not evil.

Walter White’s narrative has spawned a far-reaching fandom that inevitably reaches into the material world. Few things in Breaking Bad could be more iconic—or more personal—than Walter White’s cotton briefs. As part of an auction of Breaking Bad items, 109 people bid for the underwear that eventually sold for $9900. Much of the press on the auction was reduced to shallow curiosity over the attraction of Walt’s ill-fitting underwear or the cost of Hank’s rose quartz and Jesse’s DEA mug. Strangely enough, nearly no press expressed any surprise that underwear and television series props would be so expensive and desirable.

Few observers have really questioned why fandoms seek such prosaic things linked to fictional performances. The prosaic tighty whiteys are a relic of sorts, a material thing associated with a venerated figure. The most powerful of all relics are those things associated with the body of a saint, such as literal human remains or an item of clothing touched by the figure. Those things are invested with the symbolic power of the venerated figure who once held them, focusing secular narratives as well as triggering deeper philosophical reflections raised by the lives of saints. Read the rest of this entry

Fandom, Pilgrimage, and Media Landscapes

In the northwest of Middle Earth sits the Shire, a modest agricultural community whose verdant landscape was created and densely described by JRR Tolkien, visually interpreted in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy and the subsequent Hobbit, and dissected in enormous spatial depth by a legion of committed readers and artists. The Shire is perhaps not “real,” but it is ironically better described and far more appealing than most of the real world. Consequently, fans eager to find such a place flock to the New Zealand sets where Jackson fancied hobbits and elves might live. Half a planet away Soprano’s fans likewise have migrated to a fantasy landscape constructed in popular culture: New Jersey. The world of the Soprano’s references genuine places that have a material presence in the same way as the LOTR sets, but both fabricate a world in which New Jersey, Hobbiton, Mayberry, or Springfield are imagined places constructed from a mix of historical, social, and fantasy referents. Those narratives and the landscapes they reference underscore that the distinction between imagination and reality has long been a contrived dichotomy for many fans. The depth of that fascination is reflected in the enormous number of fans who now flock to the likes of Merlotte’s Bar and Grill, The Seven Seas Motel, The Millennium Centre, Los Pollos Hermanos, Hershel’s Farmhouse, the Bada Bing, Gaius Baltar’s House, the Double R Diner, and the crash site of Oceanic Airlines 815 intent on securing a material connection to their fandom.

Gollum caught fish in this waterfall in the second Lord of the Rings movie (image from Mike Rosenberg)

Fandoms push beyond enjoyment of a series or film, finding dimensions of their fan passion that they can relate to their everyday lives: the Soprano’s in this case becomes not a soap opera but instead a jarring and personally relevant vision of ethical ambiguity, violence, and desperation. Fandoms weave these philosophical narratives from threads drawn from a rich range of discourses: in the case of Star Wars, for instance, the canon is drawn from the films, which are in turn accented by official novelizations, cartoons, comic books, and games that are themselves reinterpreted by fan web pages, cosplayers, and fan conventions. Such participatory fan cultures draw idiosyncratically from a breadth of official and fan narratives and demonstrate mastery of the particularities of the narrative: the Star Wars fans, for instance, know all the details of the multiple Lucas edits, can identify an Anxarta-class light freighter, and can quote a breadth of Yoda aphorisms. Yet the material experience of fandom is often ignored entirely or reduced simply to purchases of some mass-produced trinkets that accompany nearly every popular cultural franchise (for a European exception, see Stijn Reijnders’ 2011 study Places of the Imagination: Media, Tourism, Culture).

Contemporary fandoms are perhaps most powerfully fueled by their digital forms in fan pages, blogs, and forums: for instance, mega-fandoms like Star Wars, LOTR, Harry Potter, and Vampire Diaries have gargantuan wiki pages that dissect the infinite particularities of the fan passions, and many more modest fandoms have devoted online spaces. Nevertheless, pilgrimage to sites like Dexter’s crime scenes or Bill Compton’s house–a phenomenon that Stijn Reijnders refers to as “media tourism”–is a critical material experience of contemporary fanhood. Fan tourism has become increasingly commonplace, but it is not a 21st-century phenomenon: Nicola Watson details 19th-century literary tourists who flocked to homes and gravesites of famous authors in Britain. Many of these sites have remained in popular consciousness: for instance, tourists began visiting Baker Street in the early 20th century to see the haunts of Sherlock Holmes (the 221B Baker Street address eventually was remodeled in 1990 to become a museum interpreting Holmes’ residence, basing the re-modeling on Arthur Conan Doyle’s descriptions of the imagined home).

The Materiality of Desperation: An Archaeology of Breaking Bad

The Albuquerque Convention and Visitors Bureau might be justifiably conflicted by the popularity of Breaking Bad, the series detailing the life of a suburban Albuquerque methamphetamine producer. A tale of a chemistry teacher turned meth dealer, the series is an unsettling moral narrative about a milquetoast’s descent into evil, but it is also a compelling visualization of the relationship between material culture and contemporary desperation. Breaking Bad paints a grim picture of Albuquerque as a prosaic, colorless landscape, imagining how commonplace suburban tracts and the southwestern desert appear in the desperate gaze of a substratum of drug users and dealers, their naïve neighbors, and an audience that anxiously contemplates its own desperation and moral plasticity. Breaking Bad’s Albuquerque is a coarse place populated by disagreeable if not outright repulsive people whose desperation and conflicted morality are heightened by a harsh material aesthetic.

The Albuquerque Convention and Visitors Bureau might be justifiably conflicted by the popularity of Breaking Bad, the series detailing the life of a suburban Albuquerque methamphetamine producer. A tale of a chemistry teacher turned meth dealer, the series is an unsettling moral narrative about a milquetoast’s descent into evil, but it is also a compelling visualization of the relationship between material culture and contemporary desperation. Breaking Bad paints a grim picture of Albuquerque as a prosaic, colorless landscape, imagining how commonplace suburban tracts and the southwestern desert appear in the desperate gaze of a substratum of drug users and dealers, their naïve neighbors, and an audience that anxiously contemplates its own desperation and moral plasticity. Breaking Bad’s Albuquerque is a coarse place populated by disagreeable if not outright repulsive people whose desperation and conflicted morality are heightened by a harsh material aesthetic.

Jesse’s apartment apparently was available for rent when this picture was taken (image Paul Varvaez)

Breaking Bad’s account of cancer-ridden high school teacher Walter White revolves around moral relativity and unravels a series of grim crises played out against the backdrop of Albuquerque. Breaking Bad’s premise has no self-evident aesthetic: unlike a series like Mad Men—which is perhaps only about style—Breaking Bad dissects a self-loathing underachiever who descends into crime, desperate to pay for medical treatment before embracing his own ethical darkness. The series provides little moral clarity distinguishing between good and evil, and its characters’ free will results in ethically problematic choices that elicit an uneasy sympathy for the likes of Walter White. The central material dimension of Breaking Bad’s aesthetic is a familiar harshness that reaches into faceless suburbs, inner-city neighborhoods, and vacant expanses of desert. Most Breaking Bad spaces—Mesa Credit Union, the Octopus car wash, the Crossroads Motel, Los Pollos Hermanos—exist in every community. The places that appear in Breaking Bad are likewise not at all atypical of many more communities, ranging from the abandoned spaces (e.g., the hotel where Walter did his first deal); streets and parking lots (e.g., the corner where Combo was killed); grocery stores (e.g., Hi-Lo Market), and a range of homes including modest places (e.g., Jesse and Jane’s rental), charmless condos (Walt’s temporary home), a large home in a settled neighborhood (e.g. the Pinkmans’ home), and the Whites’ commonplace suburban home. Read the rest of this entry