Blog Archives

Commerce, Execution, and the Black Corpse: Injustice and Sherman Arp

On March 10, 1893 Sherman Arp stood before a crowd that had gathered at 5:35 AM to witness his execution in Centre, Alabama. Arp had been convicted of murdering George Pogue in 1891 and was sentenced to death for the carriage-maker’s murder. In the pre-dawn twilight Arp sang spirituals in the moments before he was hung with a rope that had dispatched seven Black men before Arp. Sherman Arp’s execution, the sale of his corpse, and the suggestion that Arp was hung with the same noose used in an 1888 lynching underscore the breadth of anti-Black injustice in late 19th-century America.

Sherman Arp was born in Georgia in about 1868 and by his own account went to Alabama in 1880, where he married in September 1885. Arp and his wife had two children when Sherman was charged with the July 1891 murder of George Pogue. The Coosa River News reported in July that Pogue had been ill and his “death had been expected sooner or later, from his diseased condition, but on inspection by Dr. Elliott it was found that Mr. Pogue had been foully murdered with an axe.” Initially the murder was reported as a robbery, but in October one account identified a Black “man engaged in illegal whiskey selling,” Will Cantrell, murdered Pogue “to prevent Pogue from reporting him.” Cantrell was arrested in Georgia in early October, but he had been released by October 23rd, when it was reported that Sherman Arp was one of five men who had conspired to rob and murder Pogue. Three Black men–Arp, Alf Glenn and Abe Dixon–had been identified as conspirators with a pair of white moonshiners, Alex Burkhalter and Green Leath. Newspaper reports provided contradictory accounts of Pogue’s murder, but Glenn and Dixon had apparently had no role in the crime at all; Arp reportedly indicated he killed the elderly man in a robbery instigated by Burkhalter and Leath while at the two moonshiners’ gunpoints.

Arp was captured in Rome, Georgia, and the Centre Alabama newspaper reported that the Rome Sheriff “refuses yet to give up Arp to the authorities here, as he (Arp) claims he fears lynching if brought into this section.” A day later, though, the Sheriff took Arp back to Cedar Bluff, Alabama, where he joined Glenn, Dixon, Burkhalter, and Leath; however, the judge released the other four and committed Arp to jail to await trial. As Arp feared, “Immediately upon the announcement of the decision, the large crowd which was present, made a dash for Arp and attempted to kill him, but Sheriff Blair and Deputy Angel drew their guns and stood the would be lynchers off, until the officers got the negro in a buggy and drove rapidly out of Cedar Bluff. The mob was unmasked and would have dealt short justice if they could have got their hands on Arp.”

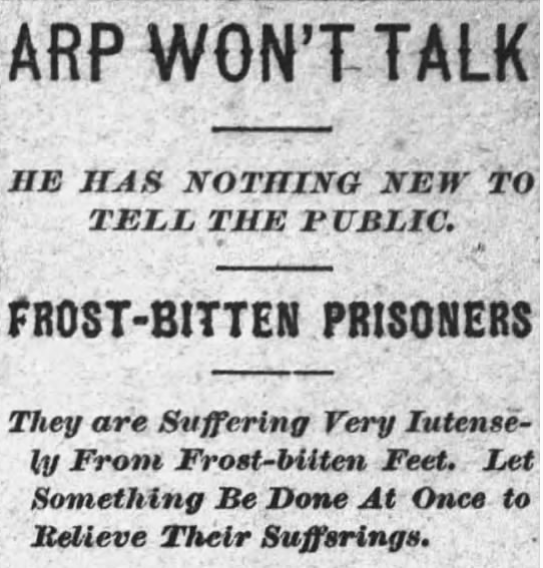

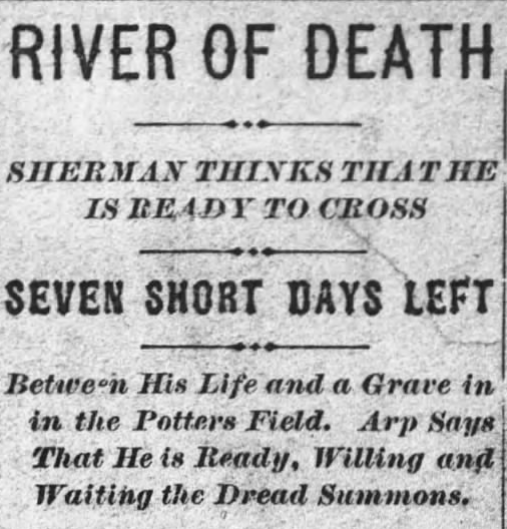

In July 1892 Arp went to trial, and on July 29 he was found guilty of murder and it was “recommended that he be hanged by the neck until he is dead, dead! dead!” He was to be hung within the week, but Arp was spared by a state Supreme Court review. The State Supreme Court rejected Arp’s appeal on January 26, 1893 and set his execution for March 10. As Arp awaited his execution he was a witness in the February trial of Burkhalter and Leath, when the two accused conspirators were found innocent. A week after their trial Arp was being imprisoned in an unheated chicken coop where his feet and hands had suffered frostbite. By February 23rd he could hear the gallows being constructed in earshot of the jail cell he had been moved to in preparation for his execution. Arp did indeed go to the gallows on March 10th, with one witness declaring that “He was as game a human as ever stood upon scaffol [sic].”

Arp reputedly was hung by a “historic rope” owned by Floyd County, Georgia that had been used to hang seven other men before Arp. The Coosa River News reported that the “rope with which Arp was executed, was the instrument of seven hangings prior to its use upon Sherman. One of these was a lynching at Summerville, Ga.” It is not clear if Arp was indeed hung by the same rope used in previous murders or executions, but in May 1888 Henry Pope was lynched in Summerville, Georgia after being seized from the Chattooga County jail. Pope had been charged with rape, twice stood trial, and was convicted for a second time in March 1888. Pope was scheduled for execution in May, but five white citizens testified that Pope had not been at the scene of the rape, and he was given a reprieve by Georgia Governor John Brown Gordon. Hearing that news, a mob raided the jail on May 1, 1888 and hung Pope. Regardless of whether Arp had shared the same noose as Pope, the invocation of the lynching cast Arp’s own execution as part of a justice system that included lynching.

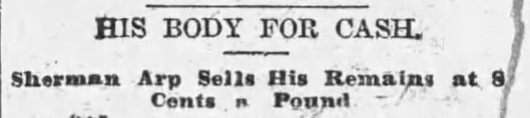

In perhaps the final dehumanization of Sherman Arp, he sold his body to a local physician. By most accounts he hawked his body by the pound. A Montgomery newspaper reported that in the week before his execution Arp informed local physicians he “desired to be weighed like a hog and sold by the pound” following an auction between those doctors. Of those physicians, “Dr. Will Darnell raised the bid to 8 cents per pound and the trade was closed. Arp went on a pair of scales and was weighed. He tipped the beam at 158 pounds. Dr. Darnell then figured up the amount and paid over to Arp $12.48 in cash and Arp gave the doctor an order for his body. Arp then proceeded to blow the money for good things to eat and drink and while it lasted he had a rousing big time.” However, one report a week later indicated that the auction tale was fictional and Arp had instead received a flat fee of $10. A week after Arp’s execution the newspaper provided an unsettling aside on masculinity and the Black corpse when it reported that “The physicians have been desecting [sic] Arp’s body since his execution. He was a well developed specimen of physical manhood.”

This narrative witnessing to Sherman Arp’s fate risks fixating only on the final tragic part of his life, but his story underscores the ways racism constrained and valued Black life. Exacting justice on Arp by inflicting frostbite before his execution—and then hawking his corpse for dissection—underscores the ways that racist justice was projected onto Black bodies. The fascination with the rope that had reputedly served as both hangman’s and lynchers’ noose reflected the ways execution and lynching were both accepted sentences in a racist justice system. In 1964, a historical account in Centre’s Cherokee County Herald confirmed the interchangeability of execution and lynching in historical memory. Clyde Walden Reed reminisced that “We had a few lynchings in those days, also hangings by court order. I remember when Sherman Arp was hanged Oct. 10, 1893 [sic].” Rather than suggest that Arp’s story is an aberration in the American experience, it instead is precisely the sort of dehumanizing indignity that racist injustice imposed on many now-anonymous targets even as it delivered an implicit warning to Black observers.