Imagining Heritage: Selfies and Visual Placemaking at Historic Sites

A variety of ideologues routinely reduce selfies to yet another confirmation of our mass superficiality. Instagram is indeed littered with scores of us primping for our bathroom mirrors and posing at arm’s length for “ego shots”: it seems infeasible to salvage especially profound insight into contemporary society from Justin Bieber’s self-involved posing or Kim Kardashian’s often-ridiculous stream of booty calls. Nevertheless, the countless online selfies register a self-consciousness about appearance that is likely common in every historical moment, and the recent flood of online selfies may simply confirm that we know we are being seen and we are cultivating our appearance for others. After looking in the mirror for millennia, digitization has provided a novel mechanism to re-imagine, manipulate, and project a broad range of personal reflections into broader social space.

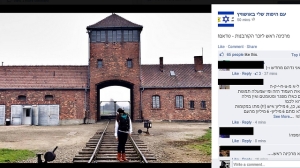

Last week a New Yorker article fueled selfie critics who lamented the apparent narcissism of selfies at Auschwitz. The page was removed after a host of media decried self portraits at the concentration camp and rejected (or simply did not comprehend) the page’s clumsy attempt to use irony to assess the holocaust’s social meanings. The Israeli page collected youths’ concentration camp selfies, and the images push irreverence and irony beyond many peoples’ tolerance: the page included typical selfie poses of pouting expressions and stylized self-contemplation, but these selfies were at places like the iconic Auschwitz gates or had sarcastic added descriptions such as “Even here I’m drop dead gorgeous!”

The strained irony of the facebook page was wasted on most audiences eager to patrol memorialization ethics or unable to fathom an ironic critique of holocaust symbolism. Countless tourists take pictures at historic sites including Auschwitz every day, though, and those pictures include numerous crass images shared with the internet. Yet selfies seem to break some unwritten codes about heritage tourism, especially in visits to dark historical spots. Tourists’ arm-length self portraits at historic sites appear to represent only a modest percentage of the countless publicly accessible selfies. Nevertheless, there are scores of selfies taken at nearly every heritage site that a tourist would snap an otherwise mundane image. A host of selfies have been taken at the 9/11 Memorial, for instance, and some photographers themselves concede that the setting is perhaps awkward. Numerous visitors to Washington DC pose in front of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial for a selfie, in some cases reproducing King’s iconic statuary stance. Totem and Taboo collects images of gay men’s Grindr profile images taken at the Berlin Holocaust Memorial.

In the case of Auschwitz there are genuine codes against some photography (e.g., of the human hair on display or the Block 11 cellars), but most historic sites’ photography rules simply focus on collection preservation. Some selfies may violate the unspoken ethics of respectful memorialization, and perhaps a selfie at Mount Vernon, Hadrian’s Wall, Graceland, Dealy Plaza, the Parthenon, or Monticello has somewhat different ethical dimensions than an image from Auschwitz, Treblinka, or Mauthausen. Nevertheless, it is simplistic to reduce all those tourist images—including selfies—to ego exhibitions. It also makes some sense to examine the distinctive social work of tourist selfies that contrasts to the broad range of self-taken images that get classed as selfies.

Many historical places are already in our visual memory because of the photographers who went before us: for instance, Auschwitz’s iconic gates, approaching train tracks, and razor wire fences are rooted in our collective visual imagination because of wartime photography and a host of popular cinematic depictions. Photographer Roger Cremers suggests that Auschwitz is so well-known visually that he chose to document tourists’ photographic experience at Auschwitz with an eye toward illuminating how visitors visually document a place that is simultaneously familiar while its meaning is rooted in unimaginable evil that is difficult to articulate. Not surprisingly, many tourists at Auschwitz reproduce familiar settings and normatively document the same visuals; many selfies at historic sites likewise seek out the familiar vista on a site like the US Capitol, Big Ben, Disneyland, or the Statue of Liberty.

In the wake of the New Yorker article a few people on the Auschwitz facebook page lobbied to eliminate photography at the site altogether, but this position probably underestimates the anxious self-consciousness many photographers feel at contested historical sites. In his study of youth visiting Auschwitz, Thomas P. Thurnell-Read found that every visitor he interviewed was conflicted by photography, but all apparently still took photographs. A 21-year-old Canadian tourist acknowledged that “I didn’t want to turn it into a spectacle because that would bother me later. But I wanted to know, like I wanted to remember. I almost regret it but I took two photographs in the crematorium…and, I was, like, what am I doing? But, I did.” For Thurnell-Read’s subjects, simply seeing Auschwitz was insufficient, even though many indicated they knew the visual images of camps from wartime photography and popular sources like Schindler’s List. Their camp photographs were meaningful and even authentic because they were based in a personal experience of the camp space and were not simply a series of disembodied images.

Elizabeth Losh’s study of the Selfiecity database argues that selfies are a transnational phenomenon that is about place-making and not simply the exhibition of faces and bodies. Like a host of tourist pictures that preceded them, the selfies and digital photo albums are partly place-making projects in which the sense of a historic place is fabricated around a tourist’s gaze. A selfie essentially writes its subject into history and visually invokes a heritage without articulating its meaning; in many of these most complicated histories, a picture of the Auschwitz gate or the 9/11 Memorial panels invokes much more fluid and personally idiosyncratic meanings than a textual narrative of the experience.

Many observers seem to consider selfies a uniquely narcissistic generational transgression of appropriate historical solemnity. The critique of youth behavior at historic sites perhaps betrays a deeper anxiety of the perpetual identity fabrication that Sherry Turkle argues many adolescents are engaging in on facebook, Instagram, snapchat, etc. The tendency to document experience and self visually and instantly rather than in a text-driven narrative may indeed be generational, and selfiecity’s research confirms that the average age of selfy photographers is indeed young (23.7 years of age).

The heart of selfie photography in historic sites is perhaps personal imagination; it is less what we look like—and what a historical site “really means”—than it is about what we imagine we look like and what a historical site means. One of Thurnell-Read’s subjects touring Aushwitz focused on imagination and said he “liked that it was underdeveloped, the fact that it was in ruins, again, the faculty of mind, it helps, because you had to conjure up images yourself which made you think more.” Historical selfies certainly harbor some normative ideological effects ranging from visual representation of the self to the guise of attractiveness that shapes how many people view selfies, and in some spaces we may expect some codes of dignity. Nevertheless, historical selfies simultaneously reflect a telling if idiosyncratic effort to visualize and give meaning to a personal tourist experience.

For more on selfies, see Katie Warfield’s project Making Selfies, Making Self, which focuses on young women’s experience of taking, seeing, and making social sense of selfies.

The facebook group The Selfies Research Network marshals a ton of good scholarship and popular thinking.

References

Russell Belk, Joyce Hsiu-yen Yeh

2011 Tourist photographs: signs of self. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 5(4):345–353. (subscription access)

Nadav Hochman

2014 Imagined Data Communities. Selfiecity

Patricia G. Lange

2014 Facing the Selfie. Committee on the Anthropology of Science, Technology, and Computing (CASTAC) Blog, 24 June.

Jonas Larsen

2005 Families Seen Sightseeing : Performativity of Tourist Photography. Space and Culture 2005 8(4):416-434.

Iris Sheungting Lo, Bob McKercher, Ada Lo, Catherine Cheung, Rob Law

2011 Tourism and online photography. Tourism Management 32(4):725-731. (subscription access)

Daniel Miller

2014 Know Thy Selfie. Global Social Media Impact Study Blog, 1 April.

Thomas P. Thurnell-Read

2009 Engaging Auschwitz: an analysis of young travellers’ experiences of Holocaust Tourism. Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice 1(1):26-52.

Theresa M. Senft

2014 The Epistemology of the Second Selfie: What Queer Teaches Us About Digital Display, Surveillance and Power. Paper delivered to the International Communication Association. 22 May.

Nishant Shah

2014 The Selfie and the Self: Part 1 – Hiding and Revealing. dmlcentral 16 June.

Sherry Turkle

2011 Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books, New York.

Images

Selfies at the Acropolis image from Rob

Selfie at the Lincoln Memorial image from Joe Flood

Posted on June 30, 2014, in Uncategorized and tagged #WPLongform, auschwitz, selfies. Bookmark the permalink. 16 Comments.

This is a really interesting piece, and it would be interesting to see survey data by age group about the impropriety of such behavior…I would imagine that disapproval intensity would strengthen with age, but even as a relatively young person (I’m 28), I still have pretty significant qualms with that kind of behavior

I suspect there are indeed some generational distinctions in how people view museum behavior in general and selfies in particular, but Thurnell-Read’s interview subjects all express reservations about various sorts of disrespectful behavior at Auschwitz, so it probably is not about generational experiences alone.

Great post, Paul. Loved exploring all of the links to various selfies and selfie-sites. It’s such an interesting phenomenon, and so easy to reduce it to egotism than to examine the sociocultural reasons behind it. Instead of just rolling my eyes or making a snarky comment, I’ll think of your article next time I see some “young’n” taking a selfie (and then probably roll my eyes anyway.)

Jamie Kastner did an excellent documentary on visiting Auschwitz. I was appalled that it looks like an amusement park with food stands and gift shop.

My “shiver me timbers” moment upon reflection was when I wrote this:

“What’s next, Video Game Auschwitz or perhaps Real Time Auschwitz. Why let a good theme park go to waste, the tourists can go there while it’s in operation. They’d pay more for a bit of torture or a skin lampshade, maybe prodding some bodies with electricity, with a higher fee for genitalia. Then it’s off for a hot dog and some ice cream and an afternoon of unloading trains and choosing who lives and dies, with opportunity for some souvenir clothing and jewellery, or maybe if you’re lucky you can buy a child to take home with you.”

Appalling.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this. Especially this:

“The heart of selfie photography in historic sites is perhaps personal imagination; it is less what we look like—and what a historical site “really means”—than it is about what we imagine we look like and what a historical site means.”

Best,

Dani

Thanks. Imagination seems to be my explanation for a lot of things 🙂

Fascinating work, really. I think this highlights the generational, as well as technological distinctions between two groups of people and how they assess the values of the same historical space very well.

I wonder how the selfie will operate over a longer period of time. That is to say, I think part of the reason a selfie at Auschwitz seems in poor taste is because the majority of popular conception surrounding selfies is a shallow level of self-glorification. Yet, as my generation (I’m 22) continues towards fully-fledged adulthood, there will be an inevitable series of clashes between the coincidental nature of what selfies had captured (middle school hallways, nights out at one’s favorite club) and what they will be capable of capturing (funerals, weddings, other moments of self-enlightenment). My thought is the selfie will evolve on a mental/emotional level, much like other forms of adolescent media–video games coming to my mind, as a form by which the serious and the playful have become far more entwined than I think any games studies scholar could have predicted.

–Marley-Vincent Lindsey

Reblogged this on chokangpurple and commented:

“Mass superficiality”–unfortunately has describe our generation

Great article. While visiting many churches in England, I felt conflicted about photography. When is it disrespectful? When is it helpful for remembering great events? These are questions we need to consider more often.

This is a great, well-researched article – it resonates with the ideas of Dean MacCannel’s book, “The Ethics of Sightseeing.” Look forward to reading more!

Reblogged this on Anthropology Musings of an anthro-tragic and commented:

interesting read!

Pingback: Imagining Heritage: Selfies and Visual Placemaking at Historic Sites … | fast horses

Pingback: No cutesy Latin title 4 | Me + Richard Armitage

Pingback: The #MuseumSelfie: Policing Heritage | Kaeleigh Herstad

Pingback: The Horror of Pompeii – Plaster Casts and Photography | Public Places Past and Present

Pingback: But First, Let Me Take a Historical Selfie | The Pulse