Blog Archives

Dispossession and Demolition: Razing Second Christian Church

In February 1948 Second Christian Church celebrated its move into a 1910 church on West 29th Street and Kenwood Avenue. Second Christian would be one of the longest-lived Black congregations in Indianapolis, tracing its origins to 1866 when a mission church and then several houses of worship were located throughout the Black near-Westside. The North Park Christian Church had called the neighborhood home since its formation in 1897, and in August 1909 the congregation lay the cornerstone for a new brick church on West 29th Street, where North Park held their first services in January 1910. In the post-World War II period, though, the Black community was expanding north into formerly segregated white residential neighborhoods, which included the late-19th and early 20th century homes near the West 29th Street church.

The church remained in use until just two years ago, but this week the 112-year-old house of worship was razed. In a community close to downtown, steps away from the Children’s Museum, and surrounded by longstanding residences, predatory speculators are hopeful the otherwise-undervalued property will be profitably re-sold for development. The West 29th Street church was a material reminder of the neighborhood’s complex heritage along and across the color line, and the historicity of the church and its place-based heritage could well have been invoked in remodeling and redevelopment. Instead, the church has now been effaced to become a parking lot until speculators can profitably develop the property.

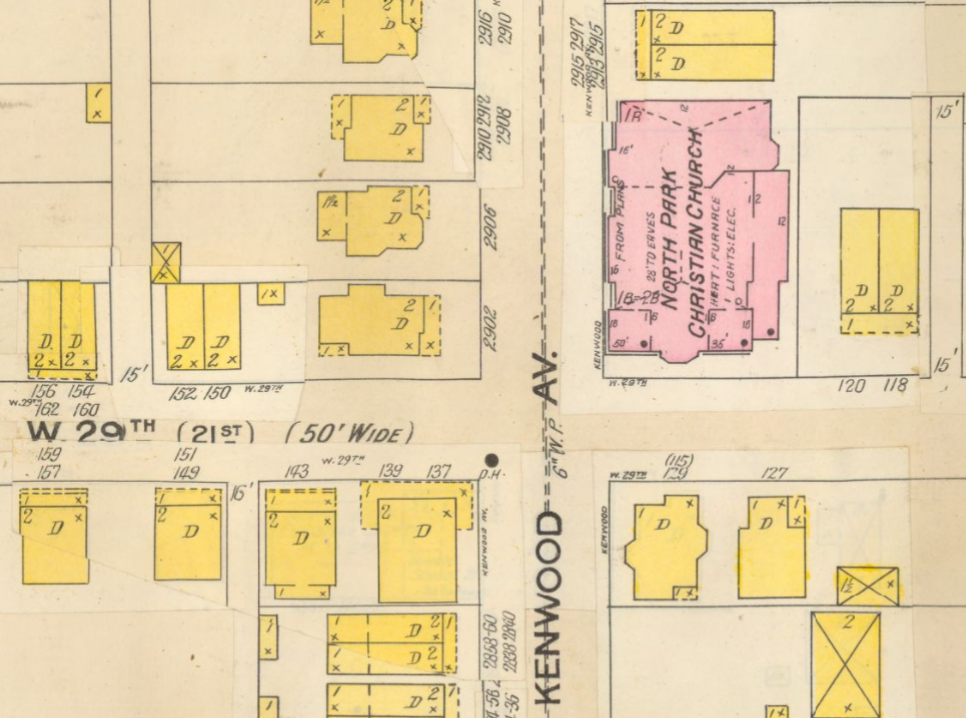

The location was first home to North Park Christian Church, which formed in June 1897 when 33 congregants initially met at Poole’s Hall at Illinois and West 30th Streets. The church elected Trustees in February 1898, and in March 1898 the congregation purchased a lot a block south for $700. Two months later they secured a building permit for a frame church they erected at the southwest corner of West 29th Street and Kenwood Avenue. Described by the Indianapolis Journal as a “suburban house of worship,” that frame church was dedicated in June 1898, when 72 people were members of the congregation. The Journal indicated the church was a “squatty” and “architecturally unique” structure with pink glass windows extending from floor to ceiling.

The surrounding neighborhood was predominately residential homes, and a scatter of businesses were located on North Illinois Street. By 1910 drug stores sat on opposite corners at the intersection of West 30th Street and North Illinois alongside an undertaker’s parlor and a series of stores with a police department station and fire house within a block. Frank Keegan, for instance, purchased the Hyde Park pharmacy on the northwest corner of Illinois and West 30th Streets in about 1893 and managed the store until retiring in 1919. Upstairs from his drug store was a dance and event space known as Mick’s Hall. James R. Phillippe owned a pharmacy on the other side of the street for 23 years; the Garrick Theatre sat on the east side of Illinois Street south of West 30th Street; and Alice Mendenhall managed a grocery store for 26 years at 3004 North Illinois Street until her death in 1924.

The growing North Park Christian Church laid the cornerstone for a new church on August 1, 1909 on the northeast corner of West 29th Street Street and Kenwood Avenue opposite their frame church, and the new church opened in January 1910 (compare 1909 update to 1898 Sanborn insurance map) The church was one of the earliest designs of architect Lewis Howard Sturges (1869-1941). Sturges was working in Illinois before 1900, and he came to Indianapolis in about 1906. Sturges designed a series of residential homes (e.g., 1919) and apartments (e.g., 1913) as well as retail architecture, and he designed a significant number of churches throughout Indiana. In addition to North Park Christian, in Indiana Sturges designed the Bethel Presbyterian (Knightstown, 1912), the Flora Indiana Christian Church (1913), Orleans Methodist Church (1914), First Baptist Church (Terre Haute, 1914), the Fowler Methodist Episcopal Church (1920), Milford’s Methodist Episcopal Church (1920), First Brethern Church (South Bend 1921), First Presbyterian Church (Winona Lake, 1923), Hope Presbyterian Church (South Bend, 1926), Tipton’s Presbyterian Church (1927), Ridgedale Presbyterian Church (South Bend, 1928), River Park Methodist Episcopal (South Bend, 1928), and Second Mt. Pleasant Baptist (Franklin, 1928); he also designed the Ashland, Ohio Christian Church in 1922.

The North Park Christian Church would eventually serve Black congregations for 80 years after World War II, but after World War I it sat in a segregated white neighborhood that vigorously resisted integration. In December 1920, for instance, School 36 on West 28th Street joined the Mapleton Civic Association and the Capitol Avenue Protective Association for an appearance before the School Board at which they asked “that the colored children in that district be sent to special schools.” By 1920 nearly all of the city’s public spaces and residential neighborhoods were segregated by practice, but the school segregation petition signaled a new ambition to create genuine legal codes restricting Black citizen rights. The Capitol Avenue Protective Association was a zealous advocate for residential segregation, and their President Ira Holmes appeared at the Mapleton Civic Association’s first meeting in May 1920. The new Mapleton neighborhood association elected as its first President Otto Deeds, whose wife Daisy was the President of the White Supremacy League. Holmes was a lawyer who represented Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson in his 1925 trial for the abduction, rape, and murder of an aide, Madge Oberholtzer.

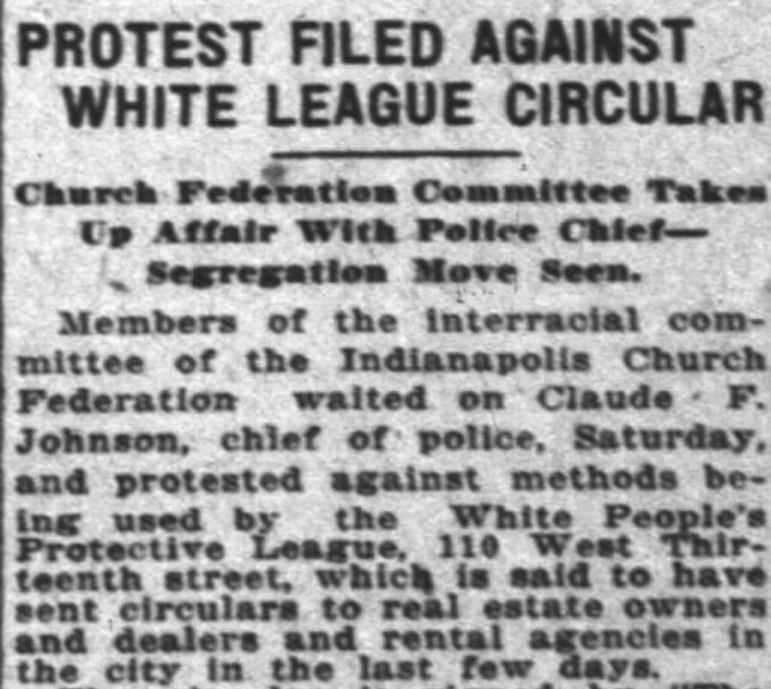

Much of the white city was similarly resistant to residential integration, forming neighborhood organizations focused on preserving racial segregation in neighborhoods like the one around the West 29th Street church. In January 1926, for instance, a group calling itself the White People’s Protective League became perhaps the city’s most vocal proponent for a residential segregation code, and all of the group’s officers lived within blocks of the West 29th Street church (though none appear to have been North Park congregants). The Protective League lobbied for a city code that would require a prospective resident to secure the written consent of the neighborhood’s racial majority before being permitted to move, and the ordinance passed in March 1926. Nevertheless, a nearly identical New Orleans law was struck down by the Supreme Court in March 1927, which rendered the Indianapolis law unconstitutional. In 1927 Black fire fighter William Goodwin and his wife Dona Hill Goodwin became perhaps the first Black residents in the neighborhood when they moved into a home at 501 West 29th Street. Their home was fire-bombed within a week, and neighbors unsuccessfully sued the Goodwins in October 1927 for deflating their property values.

On Easter Sunday 1926 the North Park Christian Church’s holiday address was delivered by the congregation’s most famous member, Governor Ed Jackson. Jackson presided over Indiana from 1925 to 1929, a period when the Ku Klux Klan was losing the grip it had held on political power in Indiana since 1923. Jackson was Indiana’s Secretary of State in 1920-1924 and was closely associated with the Klan’s leaders. Jackson was never confirmed to be a member of the hooded order, but as Secretary of State he lobbied Governor Warren McCray to support the Klan agenda. Jackson’s 1925 victory was dependent on courting the Klan’s interests, and when US Senator Samuel Ralston died in 1925 Jackson appointed a replacement approved by D.C. Stephenson. When Stephenson was convicted of the 1925 rape and murder of Madge Oberhaltzer he expected Jackson to pardon him. However, Jackson refused to pardon Stephenson, and the former Grand Dragon revealed his history of bribery of state officials including Jackson. Stephenson revealed that in 1923 Jackson had approached Governor McCray on behalf of Stephenson with a $10,000 bribe that McCray rebuffed. In 1927 Jackson was charged with bribery and stood trial while Governor, escaping with a hung jury in 1928. Jackson continued to teach the men’s Bible class at North Park after his term ended (his wife taught the women’s class). He was a Trustee for the church and continued as a congregant until he retired to his rural Orleans, Indiana farm in 1937.

In January 1930 North Park Christian Church united with the congregation of University Place Christian Church to become University Park Christian Church. The new congregation held its Sunday services at the West 29th Street church, but in the wake of World War II, the surrounding community rapidly became a predominately Black neighborhood. Second Christian Church was a Black church that traced its origins to March 1866, worshipping in a church at 11th Street and Lafayette Road that was reportedly “built out of lumber from an old Civil War barrack.” The congregation subsequently moved to two other churches in the predominately Black near-Westside, and they were worshipping at 13th and Missouri Streets when they laid a cornerstone for a new church at 9th and Camp Streets in May 1910. Henry Louis Herrod (1875-1935) became Second Christian’s Pastor when he came to Indianapolis in 1901, graduating from Butler University in 1903. Herrod became director of Flanner House in 1925 while directing Second Christian during a period of steady growth, and he remained Pastor until his death in 1935.

When the congregation purchased the West 29th Street church in 1948, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that the 227 of the 397 Second Christian congregants lived north of 16th Street. The neighborhood surrounding the church rapidly became a predominately Black community after the war. When the Indianapolis Community Plan committee of the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce mapped the “Distribution of Negroes in Indianapolis” in 1946, the neighborhood within a block of the West 49th Street church was identified as Black. The congregation expanded the church in 1974, and in 1977 under T. Garrett Benjamin Jr. the church counted over 1600 members. However, by 1977 the interstate had been built just blocks west of the church, displacing numerous postwar Black residents and destabilizing small businesses and churches near the church. The West 29th Street church was too small to accommodate the congregation, which had swelled to over 3000 members by 1982. In July 1982 the congregation moved to a church on East 38th Street that they reportedly purchased for $1.5 million. The congregation was renamed Light of the World Christian Church in 1984, and in 2002 they broke ground for a new church at 4646 Michigan Road that opened in July 2003.

Their former home on West 29th Street became home to New Liberty Missionary Baptist Church in July 1983, but they became the last congregation to worship in the 1910 church. In June 2019 the property was purchased by Brougher Plaza LLC. A demolition permit indicates the church was razed for parking, but it will almost certainly be targeted for development. The massive church might well have been remodeled and repurposed in ways that preserve the space’s rich heritage and use its very historicity as an attraction for potential residents, but the 112-year-old church was instead leveled. Emptying the lot effaces the neighborhood’s material heritage and renders it “placeless”: that is, the resulting non-descript parking lot is disconnected from any material traces of cultural heritage. Razing the church is dispossession that removes the public materiality of history, a maneuver that allows developers to imagine it as a “blank” space to build yet more interchangeable architecture.

Disenfranchised Design: Development and African-American Placemaking on Indiana Avenue

A 1950’s view of the 700 block of Indiana Avenue (image O. James Fox Collection, Indiana Historical Society, click for expanded view).

In January 1968 a group of African-American entrepreneurs and community activists gathered in the Walker Theater with the Director of the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission to determine the future of Indiana Avenue. Alarmed by the decline of the businesses along the historically African-American Avenue and frustrated by their inability to defy urban renewal projects, the group hoped to encourage investment in Avenue enterprises. Advocating strategies that have since become common in placemaking discourses, entrepreneurs had ambitious plans championing “a renewed civic and business vitality in the area of Indiana Avenue.” Their proposals included promoting cultural tourism focusing on the Avenue’s jazz history, proposing to create “a `Bourbon Street’ type entertainment and shop section … in the fashion of New Orleans’ famed `Bourbon Street’ long a mecca of Dixieland jazz.”

Yet business people were justifiably reluctant to invest their own capital because of the unpredictable effects of “slum clearance” displacements, highway construction, and the growth of the joint Indiana University and Purdue University campus that became IUPUI. The Indianapolis Recorder soberly reported on the absence of funding for such development, noting that “insurance and loans are virtually impossible for business-men on Indiana Avenue to secure since this section is considered a `high risk’ area.” The certainty of more renewal projects led one Avenue businessman to complain that “`We’ve seen from past experience that when these people come and take your property they pay as little as possible. I just can’t see how we could recover the money we might spend to fix up the area.’” Read the rest of this entry

Imagining the Urban Wilderness: The Rhetoric of Resettling the 21st-Century City

Milhaus’ Mosaic at Artistry complex on Market Street is typical of the wave of recently constructed apartments in Indianapolis’ core with modest clusters of historic homes scattered around them.

This week Indianapolis Monthly sounded a familiar celebration of downtown living when it nostalgically remembered the city’s first “urban pioneers” who settled historic homes in the wake of postwar urban renewal. The enthusiasm for new urbanites, rehabilitating historic properties, and fresh development are typical threads of 21st-century city boosterism. Such rhetoric fancies that young well-educated bourgeois will reclaim the city from ruins, optimistically envisioning a future urban landscape of “apartment dog parks and rooftop pools.” Indianapolis Monthly’s enthusiasm for a radically transformed urban core is not at all unique and not necessarily completely misplaced. Nevertheless, its celebration of “urban pioneers” and development ignores the heritage of postwar urban displacement and evades the structural inequality that makes gentrification possible.

Indianapolis Monthly’s unvarnished celebration of development extends postwar urban renewal rhetoric and has its roots in late-19th century nationalist ideologies. The metaphor of new urbanites as “pioneers” evokes an imagination of America most clearly articulated at the end of the 19th century by historian Frederick Jackson Turner. Turner argued that American history and our very national personality are rooted in our experience of the American frontier as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization.” Pioneers stood at the boundary of the frontier, where they appropriated “free land” based on a distinctively American individualism, self-reliance, ambition, and egalitarianism rooted in our presumed right to secure land and entertain the potential for prosperity.

When contemporary urban champions invoke the metaphors of frontier, pioneer, and wilderness they are participating in a longstanding discourse that assumes that transformations in the city and the nation’s broader spatial and social fabric are wrought in the interests of America. Observers have long described and rationalized urban renewal and transformation using that same language. In 1957, for instance, Baltimore’s The Sun indicated that “urban renewal has been described as the new American frontier.” The Sun invoked concepts that would have been familiar to Turner when it referred to the residents of one Baltimore block as “urban pioneers” who are “an example of the pioneering spirit, in the old sense of men and women working for themselves to create a better, brighter life though in a new-style wilderness of blight, an asphalt jungle. Without that spirit of self-help and individual initiative, the whole expensive machinery of urban renewal may grind away for years without changing more than the external appearances of slum housing.” The Sun’s analysis circumspectly approved urban renewal projects while it celebrated the residents who it presumed had sufficient initiative, ambition, and commitment to revive the dying city. Read the rest of this entry