Blog Archives

Dispossession and Demolition: Razing Second Christian Church

In February 1948 Second Christian Church celebrated its move into a 1910 church on West 29th Street and Kenwood Avenue. Second Christian would be one of the longest-lived Black congregations in Indianapolis, tracing its origins to 1866 when a mission church and then several houses of worship were located throughout the Black near-Westside. The North Park Christian Church had called the neighborhood home since its formation in 1897, and in August 1909 the congregation lay the cornerstone for a new brick church on West 29th Street, where North Park held their first services in January 1910. In the post-World War II period, though, the Black community was expanding north into formerly segregated white residential neighborhoods, which included the late-19th and early 20th century homes near the West 29th Street church.

The church remained in use until just two years ago, but this week the 112-year-old house of worship was razed. In a community close to downtown, steps away from the Children’s Museum, and surrounded by longstanding residences, predatory speculators are hopeful the otherwise-undervalued property will be profitably re-sold for development. The West 29th Street church was a material reminder of the neighborhood’s complex heritage along and across the color line, and the historicity of the church and its place-based heritage could well have been invoked in remodeling and redevelopment. Instead, the church has now been effaced to become a parking lot until speculators can profitably develop the property.

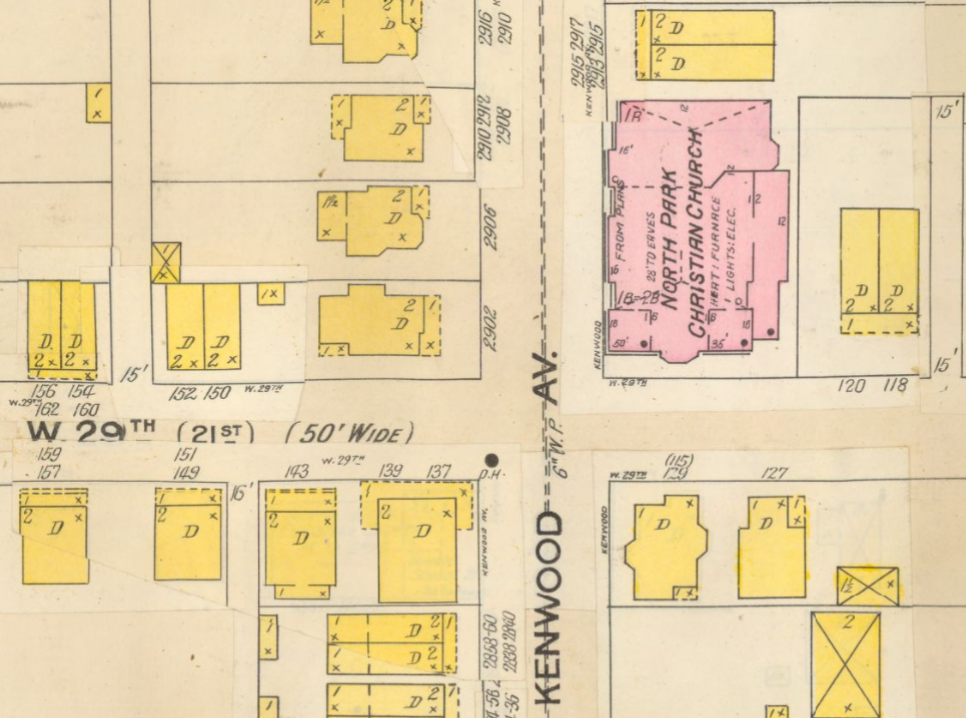

The location was first home to North Park Christian Church, which formed in June 1897 when 33 congregants initially met at Poole’s Hall at Illinois and West 30th Streets. The church elected Trustees in February 1898, and in March 1898 the congregation purchased a lot a block south for $700. Two months later they secured a building permit for a frame church they erected at the southwest corner of West 29th Street and Kenwood Avenue. Described by the Indianapolis Journal as a “suburban house of worship,” that frame church was dedicated in June 1898, when 72 people were members of the congregation. The Journal indicated the church was a “squatty” and “architecturally unique” structure with pink glass windows extending from floor to ceiling.

The surrounding neighborhood was predominately residential homes, and a scatter of businesses were located on North Illinois Street. By 1910 drug stores sat on opposite corners at the intersection of West 30th Street and North Illinois alongside an undertaker’s parlor and a series of stores with a police department station and fire house within a block. Frank Keegan, for instance, purchased the Hyde Park pharmacy on the northwest corner of Illinois and West 30th Streets in about 1893 and managed the store until retiring in 1919. Upstairs from his drug store was a dance and event space known as Mick’s Hall. James R. Phillippe owned a pharmacy on the other side of the street for 23 years; the Garrick Theatre sat on the east side of Illinois Street south of West 30th Street; and Alice Mendenhall managed a grocery store for 26 years at 3004 North Illinois Street until her death in 1924.

The growing North Park Christian Church laid the cornerstone for a new church on August 1, 1909 on the northeast corner of West 29th Street Street and Kenwood Avenue opposite their frame church, and the new church opened in January 1910 (compare 1909 update to 1898 Sanborn insurance map) The church was one of the earliest designs of architect Lewis Howard Sturges (1869-1941). Sturges was working in Illinois before 1900, and he came to Indianapolis in about 1906. Sturges designed a series of residential homes (e.g., 1919) and apartments (e.g., 1913) as well as retail architecture, and he designed a significant number of churches throughout Indiana. In addition to North Park Christian, in Indiana Sturges designed the Bethel Presbyterian (Knightstown, 1912), the Flora Indiana Christian Church (1913), Orleans Methodist Church (1914), First Baptist Church (Terre Haute, 1914), the Fowler Methodist Episcopal Church (1920), Milford’s Methodist Episcopal Church (1920), First Brethern Church (South Bend 1921), First Presbyterian Church (Winona Lake, 1923), Hope Presbyterian Church (South Bend, 1926), Tipton’s Presbyterian Church (1927), Ridgedale Presbyterian Church (South Bend, 1928), River Park Methodist Episcopal (South Bend, 1928), and Second Mt. Pleasant Baptist (Franklin, 1928); he also designed the Ashland, Ohio Christian Church in 1922.

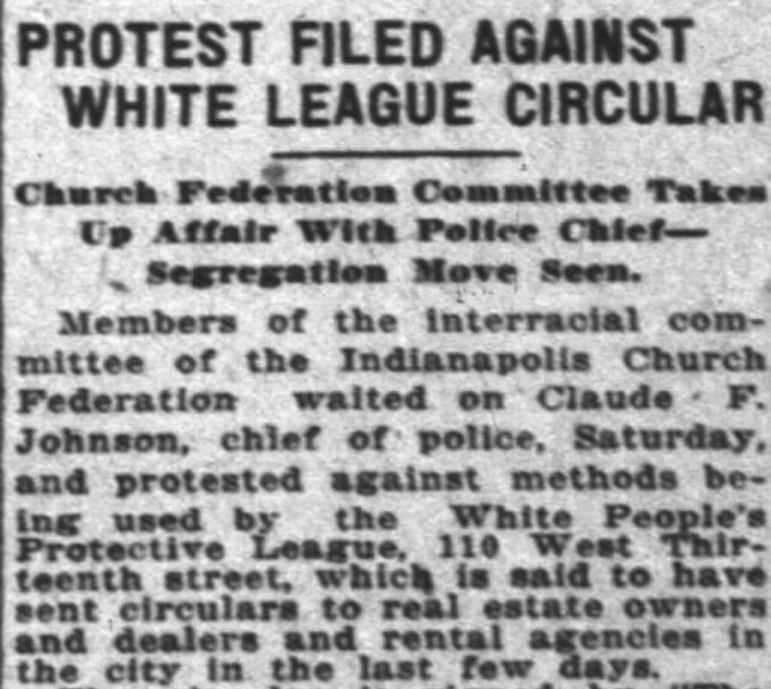

The North Park Christian Church would eventually serve Black congregations for 80 years after World War II, but after World War I it sat in a segregated white neighborhood that vigorously resisted integration. In December 1920, for instance, School 36 on West 28th Street joined the Mapleton Civic Association and the Capitol Avenue Protective Association for an appearance before the School Board at which they asked “that the colored children in that district be sent to special schools.” By 1920 nearly all of the city’s public spaces and residential neighborhoods were segregated by practice, but the school segregation petition signaled a new ambition to create genuine legal codes restricting Black citizen rights. The Capitol Avenue Protective Association was a zealous advocate for residential segregation, and their President Ira Holmes appeared at the Mapleton Civic Association’s first meeting in May 1920. The new Mapleton neighborhood association elected as its first President Otto Deeds, whose wife Daisy was the President of the White Supremacy League. Holmes was a lawyer who represented Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson in his 1925 trial for the abduction, rape, and murder of an aide, Madge Oberholtzer.

Much of the white city was similarly resistant to residential integration, forming neighborhood organizations focused on preserving racial segregation in neighborhoods like the one around the West 29th Street church. In January 1926, for instance, a group calling itself the White People’s Protective League became perhaps the city’s most vocal proponent for a residential segregation code, and all of the group’s officers lived within blocks of the West 29th Street church (though none appear to have been North Park congregants). The Protective League lobbied for a city code that would require a prospective resident to secure the written consent of the neighborhood’s racial majority before being permitted to move, and the ordinance passed in March 1926. Nevertheless, a nearly identical New Orleans law was struck down by the Supreme Court in March 1927, which rendered the Indianapolis law unconstitutional. In 1927 Black fire fighter William Goodwin and his wife Dona Hill Goodwin became perhaps the first Black residents in the neighborhood when they moved into a home at 501 West 29th Street. Their home was fire-bombed within a week, and neighbors unsuccessfully sued the Goodwins in October 1927 for deflating their property values.

On Easter Sunday 1926 the North Park Christian Church’s holiday address was delivered by the congregation’s most famous member, Governor Ed Jackson. Jackson presided over Indiana from 1925 to 1929, a period when the Ku Klux Klan was losing the grip it had held on political power in Indiana since 1923. Jackson was Indiana’s Secretary of State in 1920-1924 and was closely associated with the Klan’s leaders. Jackson was never confirmed to be a member of the hooded order, but as Secretary of State he lobbied Governor Warren McCray to support the Klan agenda. Jackson’s 1925 victory was dependent on courting the Klan’s interests, and when US Senator Samuel Ralston died in 1925 Jackson appointed a replacement approved by D.C. Stephenson. When Stephenson was convicted of the 1925 rape and murder of Madge Oberhaltzer he expected Jackson to pardon him. However, Jackson refused to pardon Stephenson, and the former Grand Dragon revealed his history of bribery of state officials including Jackson. Stephenson revealed that in 1923 Jackson had approached Governor McCray on behalf of Stephenson with a $10,000 bribe that McCray rebuffed. In 1927 Jackson was charged with bribery and stood trial while Governor, escaping with a hung jury in 1928. Jackson continued to teach the men’s Bible class at North Park after his term ended (his wife taught the women’s class). He was a Trustee for the church and continued as a congregant until he retired to his rural Orleans, Indiana farm in 1937.

In January 1930 North Park Christian Church united with the congregation of University Place Christian Church to become University Park Christian Church. The new congregation held its Sunday services at the West 29th Street church, but in the wake of World War II, the surrounding community rapidly became a predominately Black neighborhood. Second Christian Church was a Black church that traced its origins to March 1866, worshipping in a church at 11th Street and Lafayette Road that was reportedly “built out of lumber from an old Civil War barrack.” The congregation subsequently moved to two other churches in the predominately Black near-Westside, and they were worshipping at 13th and Missouri Streets when they laid a cornerstone for a new church at 9th and Camp Streets in May 1910. Henry Louis Herrod (1875-1935) became Second Christian’s Pastor when he came to Indianapolis in 1901, graduating from Butler University in 1903. Herrod became director of Flanner House in 1925 while directing Second Christian during a period of steady growth, and he remained Pastor until his death in 1935.

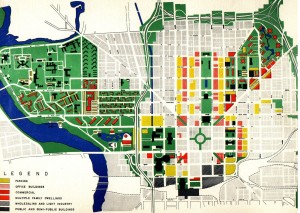

When the congregation purchased the West 29th Street church in 1948, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that the 227 of the 397 Second Christian congregants lived north of 16th Street. The neighborhood surrounding the church rapidly became a predominately Black community after the war. When the Indianapolis Community Plan committee of the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce mapped the “Distribution of Negroes in Indianapolis” in 1946, the neighborhood within a block of the West 49th Street church was identified as Black. The congregation expanded the church in 1974, and in 1977 under T. Garrett Benjamin Jr. the church counted over 1600 members. However, by 1977 the interstate had been built just blocks west of the church, displacing numerous postwar Black residents and destabilizing small businesses and churches near the church. The West 29th Street church was too small to accommodate the congregation, which had swelled to over 3000 members by 1982. In July 1982 the congregation moved to a church on East 38th Street that they reportedly purchased for $1.5 million. The congregation was renamed Light of the World Christian Church in 1984, and in 2002 they broke ground for a new church at 4646 Michigan Road that opened in July 2003.

Their former home on West 29th Street became home to New Liberty Missionary Baptist Church in July 1983, but they became the last congregation to worship in the 1910 church. In June 2019 the property was purchased by Brougher Plaza LLC. A demolition permit indicates the church was razed for parking, but it will almost certainly be targeted for development. The massive church might well have been remodeled and repurposed in ways that preserve the space’s rich heritage and use its very historicity as an attraction for potential residents, but the 112-year-old church was instead leveled. Emptying the lot effaces the neighborhood’s material heritage and renders it “placeless”: that is, the resulting non-descript parking lot is disconnected from any material traces of cultural heritage. Razing the church is dispossession that removes the public materiality of history, a maneuver that allows developers to imagine it as a “blank” space to build yet more interchangeable architecture.

The “Blank Slate” of Pastness and African-American Place

Contemporary planners, developers, and proponents of 21st-century city life routinely celebrate cities’ historicity. Urban boosters extol the appeals of historical architecture, and where that historic built environment has been destroyed those urban champions applaud new designs inspired by local architectural heritage. Few neighborhoods would seem to lay a stronger claim on such history than Indianapolis’ Indiana Avenue. Home to residences as early as the 1820s, the Avenue became a predominately African-American business and leisure district at the outset of the 20th century only to witness postwar urban renewal projects that razed nearly all of the stores, clubs, and homes along the Avenue.

Last week a Development Project Manager for Buckingham Companies enthused about the developer’s proposal to build a 345-unit five-story apartment complex in the 700 block of Indiana Avenue, calling the site a “blank slate.” The parking lot and an undistinguished 1989 office building on the site indeed reflect none of the Avenue’s rich heritage. The asphalt parking lots and a functional but forgettable office building are yet more evidence of the city’s historical uneasiness with appearing to deter development after they had been vocal advocates for extensive urban displacement projects, Indiana University’s establishment and growth, and highway construction that collectively depopulated the predominately African-American near-Westside. American urban planners launched numerous similar projects after World War II that targeted African-American communities under the guide of slum clearance or community renewal, uprooting residents and then razing much of the Black urban landscape. These postwar planners hoped to build new cities, launching a host of ideologues’ fantasies for a reimagined city that would serve segregated White suburbanites who would work, play, and shop in the urban core. Read the rest of this entry

In the Shadow of the Interstate: Living with Highways

In 1972 Interstate-65 had just been completed when this aerial photograph was taken of Mary Brame’s home on West 15th Street (at the arrow). The neighboring building was a church (click on image for larger view).

In June 1973 attorney Charles Walton wrote Indiana Governor Otis Bowen on behalf of his client Mary Brame. Brame’s home sat on West 15th Street in the shadow of the recently constructed Interstate-65, which had razed virtually all of the surrounding structures and cut off West 15th Street, leaving the widow alone on a newly closed dead-end street. Walton implored the Governor to purchase Brame’s home, which he argued was “falling apart” because of the interstate’s “noise and vibrations.” The State had built a “fence up against Mrs. Brane’s [sic] home and closed down all the street leading to Mrs. Brane’s [sic] home accept [sic] one narrow extremely short street.” Walton complained that Brame “cannot sleep at night because of the noises from the highway, and as a result of this, her health is failing.”

The 1958 Central Business District plan included this map with the proposed route for Interstate-65. At 10th Street it was proposed that I-65 would continue south along West Street, but that leg was eventually rejected; I-70’s basic location was identified on the south side (click for a larger image).

Thousands of Indianapolis residents were uprooted when the state purchased their homes for interstate construction. Mary Brame was simply one of scores of people who were left to live in the shadow of newly built highways. I-65 and I-70 have legacies of displacing vast swaths of residents in the heart of Indianapolis, but they also left in their wake gutted communities compelled to negotiate a radically transformed streetscape, pollution, and noise from the newly constructed highways. A half-century after most of these interstates were constructed, planners are now once again fantasizing over new highway designs that threaten to once more destabilize many of the same neighborhoods destabilized by 1960s and 1970s highway projects.

As Mary Brame’s lawyers attempted to convince the state to purchase her home, residents of the near-Southside were likewise negotiating a radically transformed streetscape. An April 1972 story in the Indianapolis News characterized the near-Southside neighborhood around the Concord Center as once being “a city-within-a-city, with neighborhood stores and entertainment and a great deal of kinship among the residents.” But the arrival of the interstate bisected the community that been settled on the city’s southern edges for well over a century, and much of the existing streetscape was turned into dead ends at the foot of the massive earth pile holding the elevated interstate. The News admitted that “Now that the interstate is being constructed, a physical wall is being built. … There is no overpass on 1-70, and between 400 and 500 persons who live north of the interstate are isolated” (for background on the community, see the 1974 study The Near Southside Community: As it Was and As It Is and the 2012 The Neighborhood of Saturdays: Memories of a Multi-Ethnic Community on Indianapolis’ South Side). Read the rest of this entry

African-American Heritage in the Post-Renewal City

In the wake of World War II planners, developers, and elected officials spearheaded urban renewal projects that transformed Indianapolis, Indiana’s material landscape and depopulated its central core. Yet over the last 20 years the descendants of those ideologues have been gradually repopulating the Indiana capital city’s core and constructing a historicized landscape on the ruins of the post-renewal city. A relatively similar story could be told in nearly all of postwar America, where urban renewal, the “war on poverty,” and a host of local schemes displaced legions of poor and working-class people. Some creatively re-purposed structures have survived urban renewal in Indianapolis, but much of the near-Westside’s historical landscape has been erased, remains under fire, or only survives in radically new forms. It may be pragmatic (or unavoidable) to accept such a transformation of the historical landscape, but urban renewal’s material effacement of the African-American near-Westside—and the way it is now reconstructed or evoked on the contemporary landscape–inevitably will transform how that heritage is experienced.

The most recent target in Indianapolis is Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, which has sat on West Vermont Street since the congregation purchased the lot in 1869. The congregation’s origins in Indianapolis reach to 1836, and the church members were vocal abolition supporters and orchestrated movement through Indianapolis on the Underground Railroad. Bethel was among the African-American city’s most prominent institutions, hosting myriad people for worship, leisure, education, and activism alike: in 1870, residents gathered in the church to celebrate the passing of the 15th Amendment (securing African-American voting rights); in 1904 the first meeting of Indiana’s Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs was held at Bethel; in 1926 African Americans gathered at Bethel to protest a wave of segregation laws reaching from racist neighborhood covenants to high school segregation; and neighborhood residents gathered at Bethel throughout the civil rights movement. Read the rest of this entry

The Optimism of Destruction: Demolition and the Future of the Historic City

In June, 1969 Edward Zebrowski held a massive party at Indianapolis’ Claypool Hotel. The lavish Claypool opened in 1903, distinguished by its gargantuan lobby and opulent meeting rooms and the novel luxury of a private bath in each of the 450 guest rooms. Numerous conventions met at the Claypool, and in its strategic location blocks from the State Capitol the Claypool was home to both the Republican and Democratic parties and hosted a stream of politicians over three-quarters of the 20th century. On June 23, 1967, though, 300 Claypool guests including the visiting Tacoma baseball team were forced out to the street by a fire, and by the time Edward Zebrowski had his party in 1969 the hotel faced the wrecking ball.

That wrecking ball was swung by Ed Zebrowski himself, who ushered his guests outside at midnight to watch the floodlit building meet its end. Such theatrical demolition was Zebrowski’s hallmark: in 1967 Zebrowski erected bleachers and had an organ player serenade the lunchtime crowd watching the dismantling of the 12-story Pythian building. His firm dismantled much of the city’s aging architectural fabric over more than a decade of fascinating destructive spectacles, tearing down the Marion County Courthouse in 1962 (built in 1876), the Maennerchor Hall (1907) in 1974, and the Central State Hospital Department for Women (opened in 1888) in 1975. When Zebrowski was finished, he left a large sign in many of the empty lots proclaiming “Zebrowski was here.” Read the rest of this entry

Branding Urban Decline: Style and the Imagined City at Urban Outfitters

Observers who doubt marketers’ capacity to package nearly any concept may be impressed by the ambition of Urban Outfitters’ “Urban Renewal” line. Urban Outfitters aspires to make the notion of urban renewal a desirable style that signifies a “totally one-of-a-kind” vintage aesthetic disconnected from urban displacement and decline. The branding is perhaps an irreverent or innocent play on Urban Renewal’s symbolic link to urban youth culture, invoking “streetstyle” in the strained ironic juxtaposition of “new one-of-a-kind vintage.” Yet Urban Outfitters is a carefully constructed “lifestyle” brand consciously selling a caricature of urban decline to a youth demographic that their CEO described in 2012 as “the upscale homeless person” with “a slight degree of angst.” Urban Outfitters aspires to evoke the authenticity of urbanity by linking urban decline and displacement to a style embodied in its “vintage condition” wear.

Urban Outfitters has a reputation for appealing to hipster chic, catering to the consumer who is indifferent to being labeled a hipster. Most consumers accused of being hipsters are raiding thrift stores and flea markets, constructing makeshift assemblages of mixed styles and old things and typically skirting the charge of being labeled “hipster,” but the Urban Renewal line promises genuine vintage (or a persuasive reformulation of it) without descending into the flea market. Nevertheless, because the vintage shopping experience occurs in “real” places outside consumer space, the Urban Renewal line often refers to its garments’ spatial or social roots. Urban Outfitters’ British web site, for instance, invokes the garments’ ambiguous American origins by touting the Urban Renewal line as a “vintage destination” that offers everything from “one-off finds in LA warehouses to awesome pieces from the world’s most obscure flea markets.” The Urban Renewal line’s “vintage mechanic shirts” do not come from a specific place, but they secure some origins by implying class roots that evoke their salvage from proletarian closets. The Urban Renewal garment descriptions on its American web page routinely herald their “handcrafted” production in Philadelphia, where the chain was established near the University of Pennsylvania campus in 1970. Ironically, the neighborhood was transformed by genuine urban renewal that a University archival exhibit refers to as “a lasting public relations disaster” addressed by the 1990’s introduction of local retailing that included Urban Outfitters. Read the rest of this entry

The Politics of Building Aesthetics

Some buildings are not especially satisfying, plagued by unsightly aesthetics that lead architectural critics and self-styled aesthetes to debate the merits of such structures and spaces. These discourses sometimes reduce buildings to aesthetic props decorating the landscape, important for their stylistic merits or lack thereof, even if they are implicitly understood to have ambiguous social effects. Each Wednesday, the Historic Indianapolis web page features one of these unsightly structures in Indiana’s capital city chosen for its dissatisfying preservation or architectural modifications often concealing the fabric of a historic structure. The examples in the What-the-Hell (WTH) Wednesday column include some truly unique buildings, many that may well qualify as utter eyesores or demoralizing preservation failures. The tongue-in-cheek assessment of the buildings and in some cases remedies for their restoration are all well-intentioned and thoughtful, and the column’s lamentations over these buildings does indeed raise the question of how such structures are seen by their designers, residents, and neighbors. The more consequential question, though, is how such an aesthetic analysis of buildings can be extended to become an analysis of the social and moral weight of buildings and architectural spaces and link style to the structural conditions that produce “ugly” buildings.

At some level assessing architectural aesthetics is simply an individual and idiosyncratic interpretation of a building or space: one person’s experience of an oppressive brutal modernist office building may well liberate another occupant; a neighborhood derided as a “slum” may well be a welcoming home to a community despite its aesthetic and material shortcomings; and a preservationist’s “architectural disaster” may belie concrete spatial inequalities that drove impoverished and marginalized people into “historic” neighborhoods without the material resources to craft the buildings into the stylish historic homes preservationists champion from the distance. Purely aesthetic analysis risks failing to acknowledge that built landscapes are living entities connected to concrete structural inequalities with roots as deep as the buildings themselves, and even the most aesthetically unsightly buildings may have profound social and moral consequence.

This week the WTH Wednesday column took as its subject the Upper Room Apostolic Church on Indianapolis’ eastside. The modest church sits on Broadway Street, nestled in the curve of the massive junction of Interstates 65 and 70 that was carved into the community in the 1960’s (view it on Google maps). In 1958, the city’s Redevelopment Commission described the northeastern Indianapolis neighborhood where Upper Room Church sits today as “a vast blighted area.” As in many other American cities, historic neighborhoods that declined during and after the war were targeted by a state eager to dispossess the people who had made their homes in such communities, many of whom were Black, often-impoverished, and powerful voting blocks. In 1965 and 1966 alone, over 5000 households were displaced in Indianapolis for highway construction. A complex mix of federal and state authorities cut a looping interstate highway swath through the heart of Indianapolis that sliced through a series of predominately Black neighborhoods, razing scores of homes, displacing many long-term residents, and leaving the de-populated shell of historic neighborhoods declining even more rapidly.

The little Broadway Street church sits in a neighborhood known as Chatham Arch, which was platted between 1836 and 1871. Many of the smaller homes in and around the community were razed in the aftermath of World War II, and as in many other Indianapolis neighborhoods larger structures were subdivided into exponentially more makeshift rental spaces for residents desperate for work, which included many African Americans in a wave of migration out of the South. The neighborhood was placed on the National Register in 1980, and in 2000 Indianapolis Monthly dramatically proclaimed that “Once a stagnant neighborhood populated by mostly ramshackle collapsing homes, Chatham Arch now offers downtown living with a small town feel.” Of course, Chatham Arch and neighboring communities were populated by people, and not simply buildings, and the tendency to write those residents out of the analysis and history risks rationalizing displacement and simply allowing it to march on into the future. In 2006 an Indianapolis Monthly article described homeowners in the revitalized Chatham Arch as “very sophisticated buyers, and the houses are quite high dollar.” An optimistic local realtor indicated that “It used to be that there was Lockerbie and the Old Northside, and a war zone in between,” a space now occupied by Chatham Arch in the midst of the similarly gentrified Lockerbie and Old Northside communities.

Yet today many surrounding structures like the church on Broadway remain part of a landscape that is still visibly dismembered by urban renewal forces, and that story of urban inequality materialized in the Upper Room Apostolic Church may well be more important than the fancifully renovated Chatham Arch homes or the preservation shortcomings of the church itself. In August, 1866 Allen Chapel AME (i.e., African-Methodist-Episcopal) was formed on Broadway Street with eight founding members, with the church described in 1870 as being a 36 X 44 foot frame structure first occupied in Christmas, 1866. An “African” church was in the city directory in that spot in 1867, and in 1870 the congregation was identified in the city directory as “Allen Chapel (African).” In 1875 W.R. Revels was identified as the Church’s Pastor. Born in North Carolina in 1817, Willis R. Revels appeared in 1862 Indianapolis tax records as a physician; he served as a Pastor of the Bethel AME congregation in Indianapolis as well as the Bethel AME congregation in Baltimore; his brother Hiram Rhodes Revels was ordained in 1845 and was the first person of color to serve in the US Congress, elected as a US State Senator from Mississippi in 1870-1871; and Willis served as an advocate for the 28th United States Colored Troops regiment that formed in Indiana in 1863. Revels sat for his picture shortly before his death in March, 1879, and in 1887 the church appeared on a Sanborn Insurance map as a brick building sitting exactly where the Upper Room Apostolic Church sits today.

The Allen Chapel congregation built a church facing 11th Street that had its cornerstone laid in July, 1927 and the new church was dedicated in March, 1928. The building that eventually became the Upper Room Apostolic Church remained where it sits today, serving one fraternal organization and least two congregations: In 1930 the building appeared in the city directory as Allen Chapel as well as the Indiana chapter of the young men’s fraternal society the Order of DeMolay, and the fraternal remained at that address in 1940, 1951, and 1960 city directories; in 1970, it was home to Pentecostal Apostolic Church; and in 1980, it appeared in the city directory as the home of the Grace Missionary Baptist Church. In the meantime, the building certainly declined, and in 2006 a city planning document for the neighborhood characterized the Broadway Street structure’s exterior as having “major deterioration.”

Many of the Historic Indianapolis buildings that grace its Wednesday feature are truly vernacular architecture outside the pale of style and difficult to accommodate to the aesthetic and historical codes championed by preservationists. Vernacular architecture is intensely local, shaped by contextually specific environmental, cultural, market, and social influences, and many of the little homes dotting cities like Indianapolis transported a variety of ethnic and regional styles that were modified to meet the financial challenges of their makers, the ways their households changed over time, the spatial size of lots, and similar local if not personal factors. The intent of designers is not irrelevant, and some buildings are truly poorly conceived, but in an analysis of vernacular structures buildings matter as living entities with evolving stories whose aesthetics are material reflections of broader social processes. The Upper Room Apostolic Church’s story is certainly far more complicated than its momentary appearance as a preservation nightmare, and in fact the church’s aesthetics are a direct reflection of the concrete social and material processes that ravaged this and many other inner-city American communities. The story of the little church on Broadway—one with heroic figures, genuine achievement, state inequalities, and crushing decline—is by no means unique, and it might be told of any number of buildings in Indianapolis and nearly any other American (if not global) city.

Assessments of architectural style are always partial at best if they fail to embed the structures in broader social, cultural, and material context. The 31-story Trellick Tower in London, for instance, has rather polarizing aesthetic effects, a massive shaft of concrete that The Guardian recognized was long seen as a “scar [on] the west London skyline.” Completed in 1972, the brutal modernist tower was designed by Emo Goldfinger. In 1939, Goldfinger built a modernist terrace home at 2 Willow Road in Hampstead, London that razed several cottages, a move opposed by some residents that included Ian Fleming, who subsequently immortalized Goldfinger as James Bond adversary Auric Goldfinger. Emo Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower was described by The Guardian in 1999 as an example of “pure geometry, of beauty, a perfect resolution of horizontal and vertical elements,” but it was widely reviled, and Goldfinger’s career never recovered from the stigmatizating commentary that dogged Trellick Tower. Like many high-density tower blocks the building became a haven for criminals and exceptionally run-down by the early 1980s. Such buildings were moral as well as aesthetic productions meant to fashion community, though much of the high-density public housing in the United States such as Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis or Cabrini-Green in Chicago was fatally undone by racist housing administration practices. Trellick Tower, in contrast, rebounded in the 1980’s and was listed as a Grade II protected property in 1998.

The WTH Wednesday case studies include quite a few buildings in similar neighborhoods whose current condition and aesthetics are powerful stories about displacement and racially and class-based urban renewal. Preserving such structures is laudable, and the Historic Indianapolis pages have been an important advocate for grassroots history and preservation. Every community deserves to be so lucky to have thoughtful preservation voices in our midst, and in the face of a city in danger of losing much of its built heritage many buildings like this church can be demoralizing to preservationists. Yet as material culture scholars we risk writing the complicated histories of urban landscapes out of the story if we fixate on dormers, ornamental woodwork, and aesthetics and forget to link them to broader social and material processes.

Grossman, Susannah L., (2010). Demolition Men: Contemporary Britain and the Battle of Brutalism. Undergraduate Thesis, Department of Art History, University of Pennsylvania.

Mapping Campus: The Material Dimensions of Space, Experience, and Urbanization

Campus spaces are one of the most important yet overlooked dimensions of the college experience: A materially inviting campus can secure a prospective student; a campus with central social spaces produces a very distinctive student consciousness (think about UC-Berkeley, for instance); on commuter campuses, parking can profoundly dominate students’ everyday life; and small touches like public art, consumer spaces, flower beds, and pedestrian and bike-friendly planning can have a radical effect on the university experience. Universities aspire to fashion some sort of consistent experience, and spatial planning is often as critical to that as reflective pedagogy, stellar faculty, and wired classrooms. Universities attempt to focus perceptions of campus space through representations like maps and pictures, campus tours, coordinated architectural styles, and spatial mechanisms like decorative features (e.g., fountains), sidewalk layout, or signs. Inevitably, though, members of a campus community have many different perceptions of the same objective space, and those often-conflicting perceptions of an objective material thing illuminate how and why we see things in a wide range of ways.

A surprising number of maps include the “hot dog lady” who sells dogs in front of Cavanaugh Hall when the weather allows ( click on thumbnail).

Nearly every semester I ask my students to draw maps of campus to represent an objective materiality that they all share, and the maps can be remarkably different. The only directions are that students’ maps should aesthetically represent the campus in a way that seems true to their experience. Some of the idiosyncracies reflect that people with different majors know some buildings better than others; some students have been on the campus for years while others are newcomers; and commuter students approach the campus from different sides of town at various times of day (only about 1100 of 30,000 students live on campus). Others have highly individual perceptions of the space: for instance, a fire fighter once drew a map charting all the fire hydrants on campus, and disabled students have often pinpointed handicapped parking and complex access and mobility issues. Yet at another level the maps reflect how consequential spatiality is in student experience and how the campus materially shapes the way students view higher education. They also stress that campus planning is a critical public process that requires significant input that ranges across an institution and into the surrounding community, and that process should involve ethnographic rigor and material analysis and listen closely to all of us who inhabit these spaces. Every campus space and coherent landscape has its own specific meanings that are not quite the same as the campus landscape my students draw each semester, but many of the insights could be transported to somewhere other than my little corner of the urban Midwest.

As an archaeologist who works in the neighborhood now occupied by IUPUI (that is, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis), much of my attention revolves around the history of the campus space between the 1850s and 1960s. Students have no real reason to see the contemporary campus of IUPUI as “historic,” since the University was founded in 1969 and in the process virtually every trace of historic architecture was erased. IUPUI sits alongside the Indiana University Medical Center, which has been in the neighborhood since the turn of the century, and the hospital built in 1855 was surrounded by a residential neighborhood that had its first European settlers in 1820. After the turn of the 20th century it became a predominately African-American neighborhood whose heart lay in a business and leisure district on Indiana Avenue. As in many cities, federal “slum clearance” funding following World War II targeted such overwhelmingly Black communities, and between the 1950’s and 1980’s the community was displaced.

One objective of this particular exercise is to remind students that unseen urban spaces—the parking lots, interstates, and scattered vacant spaces left behind by urban renewal—have a genuine history masked by their prosaic contemporary faces. Many University campuses have obvious heritage, invoking the institution’s historical depth through architecture and landscape aesthetics. The University of Virginia’s Lawn, for instance, is ringed by structures planned by none other than Thomas Jefferson himself, and a host of communal rituals have been linked to the University’s central space since 1819. IUPUI students, in contrast, virtually never draw or refer to historical features on the campus landscape because there are no significant material cues to this heritage. The landscape around the Indiana University Medical Center has some historical architecture and spaces, including a 1929 Olmsted Brothers garden (which has never appeared on even one of the 2000 student maps I’ve graded in over 10 years), and the 1927 Madame Walker Theatre Center sits across Indiana Avenue (but it very rarely appears on student maps). Nevertheless, few IUPUI students spend much time on the Medical Campus (despite being immediately across the street), so it rarely appears as more than a rough reference or as the home to a 24-hour McDonalds. The Walker Theater sits on what was once the central thoroughfare of Black Indianapolis, but that heritage is largely unknown to most Indianapolis residents. The dilemma of ignoring the landscape’s heritage is that it risks evading the racially motivated displacement that made the University itself possible. IUPUI has worked to recognize that heritage and the University’s complicity in the neighborhood’s displacement, but much of that story appears to remain unrecognized by the students who draw campus maps in my class.

For many students, the IUPUI campus is simply overwhelmed with cars and no spaces to park them. Almost no academic buildings even appear on the map (thumbnail)

Compare the drivers’ map on the left with this cyclist’s map, which has almost no features at all (thumbnail)

The story of a commuting campus inevitably revolves around parking, and nothing is a more common focus of my map-makers than their apparently endless and universally futile search for convenient, inexpensive, and spacious parking. To compound students’ consistent displeasure with parking is Indianapolis’ deep affection for car culture, a love personified by the city’s long-term links to auto racing and underscored by its persistent resistance to mass transit, bike commuting, carpooling, and sidewalks and walkable streets. Some of this celebration of car travel has subsided in the city (for instance, the University has a carpool program and a host of inducements to seek an alternative to car commuting), but most students feel compelled to drive to campus alone and compete for a finite number of parking spots that seem to be grossly over-priced. So rather than celebrate the rich appreciation of critical thinking and diversity honed in our classrooms, many of them instead appear to associate their University experience with deep-seated anger over parking. Car culture appears unquestioned and inescapable in these maps, and for suburbanites with irregular schedules, kids, and jobs the vagaries of Indianapolis public transport, carpooling, and sweltering on a bike all are challenging to overcome. Nevertheless, there are more options than many students seem willing to concede, and few see parking as a privilege or recognize it was won by the historical displacement of a community to make way for asphalt expanses.

This colorful map includes all the essential features of college life: the ATM machine; parking; and the 24-hour McDonalds in the University Medical Center (thumbnail).

University maps are not surprisingly often quite lovely expanses of green that eliminate all the objectionables of real life and underscore the campus’ placement in nature. Compare the typical maps for Eastern University, Shippensburg University, or Jacksonville University, all oblique images bathed in green just like most rural and urban campus maps alike, including most of the IUPUI maps. Yet my students rarely depict anything from nature in the IUPUI maps, instead fixating on asphalt parking lots, brutal modernist buildings, and empty expanses in between. The University is bordered by the White River to the west, but because most students enter campus from the east they rarely depict the river. Local militias first gathered at the spot now known as Military Park in 1827, but the 14-acre park on the south side of the campus is virtually never depicted on student maps; likewise, the Indiana Central Canal built in 1836-1839 neighbors campus but has almost never appeared on a campus map (though the map on the left is an exception). The remainder of campus is largely flat stretches of asphalt and open unevenly grassed spaces punctuated by a few modest trees, so much of that open space never gets aesthetically depicted in students’ maps and appears to simply be imperceptible. Much of that space is left unrendered in drawings, or in the most detailed maps students draw sidewalks but nothing outside their sidewalk trails.

This remarkably detailed map on the left (completed prior to the construction of the Campus Center or the introduction of the smoking ban) illustrates several of the most basic insights of these maps. Penned by a smoker, it reflects how many smokers seem to know the landscape especially clearly. The map complains about parking, as do most student map-makers. This cartographer does not know exactly where the White River is located or what is on the west side of the city, though he illustrated some items from nature and the Lilly Fountain on the left side of this map, and he even notes where he and his dog come to play. His use of the parking decks, though, is not exactly how planners intend these spaces to be used.

This map includes only two academic buildings, acknowledgement that a hospital exists nearby, and the note that Medical Center employees who smoke (i.e., “smoking nurses and doctors”) are compelled to gather along 10th Street (thumbnail).

The best maps nearly always are drawn by smokers. Where many non-smoking commuter students rush into the classroom buildings and rarely linger outside, smokers spend much of their time clustered along sidewalks where they have been ushered because of smoking bans. Even before the University smoking ban smokers gathered in specific spots on campus and developed circles of students and staff who actually knew what the landscape looked like and could report on the weather. Regardless of how we feel about the health effects of smoking, it is hard to deny that it is a social activity made oddly more social by smoking bans that have driven collectives into sequestered spaces together (strangely enough along all the sidewalks coming into campus, which makes it appear that there are now more smokers than there were before the campus ban). I’ve had several smokers draw campus maps that measure distance based on how long it takes to consume a cigarette between two points, and the estimations of distance made by smokers seem remarkably accurate.

An astounding number of students do not include the University Library on their map or put it in a spot not even close to where it exists in reality. This may simply be confirmation that increasingly more students encounter scholarship in digital formats and not on dead trees or with the sage advice of skilled librarians. To some extent it may also reflect that the University Library is a rather non-descript massive cube sitting out in the midst of campus.

The shining L’s on a blazing hot Midwestern summer day. My brutal modernist office building is in the background.

One thing that students do include on many of their campus maps is public art. The campus includes a surprising number of pieces of public art, and the piece most often recognized is the work Untitled L’s, which sits in the space in front of Cavanaugh Hall, which houses most Anthropology classes. Installed in 1980, the work is three 55-foot tall steel L-shapes designed by sculptor David Von Schlegell, but student maps sometimes include anywhere between one and five L’s pointing in any number of directions (though they always get the location right). There are a variety of origin myths about the work, the most common being that several more sculptures had been commissioned but could not fit in the space; others suggest the work is simply meant to be campus seating, and on a nice day it is true that sitting or reclining on the huge L’s is comfortable. The work actually is laid out as a Pythagorean triangle and meant to evoke the logic inherent in University life. No mapper has ever recognized that intended meaning, and many seem to actively dislike the piece, but both responses may be irrelevant since the sculptures are actually seen and evoke genuine responses.

At some level this is simply an exercise in reflecting on how maps represent space in particular ways, but at another level a decade of these maps has provided a very strong sense of how students perceive campus space, and that voice is absolutely critical in any campus planning. Campus planners have been drafting costly plans for the remodeling of the campus neighborhood continually since the late 1950’s (with some really fabulous scale models of the city) and as recently as February, 2012, but the plans are at best suggestive directions for campus and city planning. The map exercise actually underscores the significance of ethnographic work with users, something most thoughtful architects already recognize, yet many students and campus community folks have clever and interesting ideas for how the space could be developed that would make the campus experience more pleasant and enriching.