Race and the River: Swimming, Sewers, and Segregation

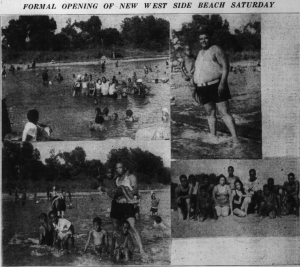

In August 1936 the Indianapolis Recorder included these images of the newly opened Belmont Park beach.

Last week Indianapolis’ tourism agency Visit Indy proposed building a beach along the White River, the waterway that meanders through the heart of Indiana’s capital city. The idea modeled on temporary beaches in Paris (where swimming is not allowed in the Seine) was greeted with some skepticism: today, much of the river has a well-deserved reputation for pollution reaching back over the last century. The river and its urban tributaries have long been fouled by combined sewer overflows, industrial discharges, and upriver farm wastes, and many stretches of the river are inaccessible and unappealing. The Indianapolis press seem unable to imagine the White River as a tourist spot with something akin to a beach, but the river has a rich history of waterfront leisure that has included beaches from Ravenswood and Broad Ripple south to the edges of present-day downtown. Some of the most polluted stretches of the White River also wind through predominately African-American neighborhoods and attest to how segregation shaped African Americans’ experience of the river.

In 1916 the Indianapolis News delivered an alarming report that the White River from Washington Street south “is devoid of natural fish life and birds.” Below the West Washington Street bridge the State Board of Health’s John C. Diggs pronounced the river “a malodorous, septic stream, bearing on its surface floating matter of sewage origin,” concluding that the river “was of the same character as ordinary household sewage.” Two years before he told the American Chemical Society conference that “White River is a comparatively small stream, yet it is used as a source of public water supply and sewage disposal for over 300,000 people.” The 1916 study had already recognized that certain stretches of the river were more polluted than others. At Broad Ripple “the river is free from floating matter or objectionable odor”; at Crow’s Nest just south of Broad Ripple “water is clear, free from floating matter”; and at Emrichsville Bridge (just south of the present-day 16th Street Bridge) the “water is clean but has a slightly weedy odor.” However, the African-American near Westside lay directly north of the industrial pollution wreaked by companies like the Kingan and Company meat packing plant, near which “the surface is a black scum” and “bubbles of gas rise to the surface.” Their neighbors Van Camps were responsible for “pieces of tomatoes…on the surface of the water.”

Many of these conditions grew worse and expanded throughout the city’s waterways in the subsequent years. Into the 1950s Indianapolis constructed combined sewer systems, whose overflows made this situation worse along much of the White River’s course and its Fall Creek tributary. During heavy rainfalls that the sewer cannot accommodate, raw sewage is ejected into the city’s waterways. In 2006, about 7.9 billion gallons of raw sewage were flushed into local waterways, yielding e. coli contaminations 100 high times higher than safe for swimming.

In contrast, during the early 20th century beaches could be found along scattered northern reaches of the White River in Ravenswood, Arden, and Broad Ripple. Crowds had flocked to Broad Ripple by the late 19th century, and in 1906 the White City Amusement Park opened. In 1908 fire leveled the park and its four acre concrete-lined pool along the riverside, but residents could be found swimming along nearly every stretch of the White River and Fall Creek.

Indianapolis’ public parks rapidly segregated in the early 1920’s, and the city’s segregated African-American Douglass Park was opened in 1921. Douglass Park remained the city’s only public Black pool into the late 1950’s, but Douglass Park was a very long walk for many African Americans, who continually pressed for safe, convenient, and un-polluted swimming spaces. In 1927, for instance, Henry Fleming led a group of African-American entrepreneurs who announced a plan to purchase the former Casino Gardens along White River (today known as Municipal Gardens). The Casino Gardens owner had been unable to sell the property to the city’s Parks Board, but Fleming believed he had assembled sufficient funds to convert the location into the Spring Hill Country Club. Fleming touted the venue’s riverfront location and plans to develop a beachfront along the White River, but the Parks Board threatened to condemn the property if it was sold to African Americans. In June, 1933 the newly opened Eaglewood Beach promised to be a “sojourn in heaven,” offering swimming and recreation “in company with Refined folks.” The far-Westside swimming and picnic grounds located off present-day High School Road along Eagle Creek appeared to have closed at the end of the 1933 season.

A 2014 image of the Emerichsville dam facing west toward the former Belmont Park Beach (image Garrett Wilson).

Many African Americans swam in the White River and Fall Creek, and in June, 1934 the Indianapolis Recorder’s Lee A. Johnson lamented that “drowning season is on.” Indeed, a month earlier a 17-year-old had drowned in Fall Creek. In August 1936 the closest precedent to a downtown Indianapolis beach opened when an African-American beach was cleared on the west side of White River adjoining Belmont Park (now known as Mozel Sanders Park). Located near the Emrichsville Dam and south of present-day 16th Street, the beach was within an easy walk of the near-Westside. Yet by 1941 the Indianapolis Recorder was complaining that the beach was poorly maintained and dead fish were floating alongside swimmers. In 1949 the newspaper again called for public swimming pools and quoted North Indianapolis Civic League spokesman Jesse Posey who said that “our west side kids swim in the Canal, Fall Creek or White River—all polluted waters. The water kills the fish but our youngsters are swimming in it.”

The conditions that fouled city waterways along the banks of the White River downtown remain remarkably resilient. New sewers built on the north side of Indianapolis since the 1960s were hooked into combined sewers in the city, making sewer overflows even worse along tributaries like Fall Creek, which are in predominately African-American neighborhoods. In 1999 a federal civil rights complaint was filed against the city for its inability or unwillingness to address sewer overflows, and the administration of Mayor Stephen Goldsmith (1992-2000) sued the state in 1999 when it claimed that it could not financially meet the state’s environmental requirements to make the water “swimmable.”

The rehabilitation of the river into something akin to a beachfront may well require a sustained effort to address a long history of pollution, and some stretches of the river and its urban tributaries will require some reflective management to allow nature a fair foothold. Nevertheless, the White River could be the heart of a rich narrative examining Indianapolis’ relationship with the bodies of water that run through it, and it might provide a powerful lens to discuss environmental racism. A beach might well be an interesting point to begin such a conversation.

References

Charleen Coffing

1937 A quantitative study of the phytoplankton of the White River canal, Indianapolis, Indiana. Butler University Botanical Studies Volume 4, Article 3.

John C. Diggs

1914 A Sanitary Survey of White River. The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 6 (8): 639–640.

Joseph M. Fenelon

1998 Water quality in the White River basin, Indiana, 1992-96. US Geological Survey, Vol.1150.

Walter F. Schlech et al.

1983 Recurrent urban histoplasmosis, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1980–1981. American journal of epidemiology 118(3): 301-312.

Evan West

2006 Pipe Dreams. Indianapolis Monthly June 147-151, 285-287.

Connie J. Ziegler

2007 Indianapolis Amusement Parks, 1903-1911: Landscapes on the Edge. Master’s Thesis, IUPUI Department of History.

Image

Emerichsville Dam image from Google Maps Garrett Wilson

Posted on February 22, 2016, in Uncategorized and tagged African American history, environmental racism, Indianapolis, swimming. Bookmark the permalink. 4 Comments.

I love this idea. Let’s rehabilitate the river! Make it beautiful! I went to San Antonio years ago and the river walk was my highlight. Prosperous and beautiful and attractive. It should be clean and for all to enjoy! Fuck the polluters and let’s get back to real living.

Good information! Does the Indiana Historical Society have any information about Belmont Beach and segregated parks and swimming pools in Indianapolis?

IHS does have some images from Douglass Park. Ball State holds many of the Indianapolis Parks architectural drawings but does not really include much material on the social history of the parks or segregation.

Pingback: Seeing the White River: Visual Heritage in Riverside Park | Archaeology and Material Culture