Blog Archives

Race and the River: Swimming, Sewers, and Segregation

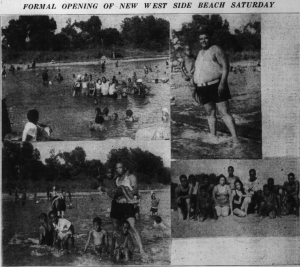

In August 1936 the Indianapolis Recorder included these images of the newly opened Belmont Park beach.

Last week Indianapolis’ tourism agency Visit Indy proposed building a beach along the White River, the waterway that meanders through the heart of Indiana’s capital city. The idea modeled on temporary beaches in Paris (where swimming is not allowed in the Seine) was greeted with some skepticism: today, much of the river has a well-deserved reputation for pollution reaching back over the last century. The river and its urban tributaries have long been fouled by combined sewer overflows, industrial discharges, and upriver farm wastes, and many stretches of the river are inaccessible and unappealing. The Indianapolis press seem unable to imagine the White River as a tourist spot with something akin to a beach, but the river has a rich history of waterfront leisure that has included beaches from Ravenswood and Broad Ripple south to the edges of present-day downtown. Some of the most polluted stretches of the White River also wind through predominately African-American neighborhoods and attest to how segregation shaped African Americans’ experience of the river.

In 1916 the Indianapolis News delivered an alarming report that the White River from Washington Street south “is devoid of natural fish life and birds.” Below the West Washington Street bridge the State Board of Health’s John C. Diggs pronounced the river “a malodorous, septic stream, bearing on its surface floating matter of sewage origin,” concluding that the river “was of the same character as ordinary household sewage.” Two years before he told the American Chemical Society conference that “White River is a comparatively small stream, yet it is used as a source of public water supply and sewage disposal for over 300,000 people.” The 1916 study had already recognized that certain stretches of the river were more polluted than others. At Broad Ripple “the river is free from floating matter or objectionable odor”; at Crow’s Nest just south of Broad Ripple “water is clear, free from floating matter”; and at Emrichsville Bridge (just south of the present-day 16th Street Bridge) the “water is clean but has a slightly weedy odor.” However, the African-American near Westside lay directly north of the industrial pollution wreaked by companies like the Kingan and Company meat packing plant, near which “the surface is a black scum” and “bubbles of gas rise to the surface.” Their neighbors Van Camps were responsible for “pieces of tomatoes…on the surface of the water.” Read the rest of this entry