Blog Archives

Consuming Indiana Avenue: Memory, Marketing, and Jazz Heritage in Indianapolis

In 1953 guests gathered on Indiana Avenue at the Sunset Terrace (Indiana Historical Society, click for expanded view).

In 2004 a typical Indianapolis Star celebration of jazz history fantasized performers and audiences united by music, suggesting that Indiana Avenue “was known for an atmosphere of camaraderie. … What’s most notable is that this was the only place in which blacks and whites could mingle socially prior to integration.” Jazz history is routinely invoked in Indianapolis to suggest that music has long been an expression of White and Black peoples’ common humanity. African-American expressive culture has an undeniably rich heritage in the theaters, clubs, churches, schools, and homes dotting the near-Westside. From the end of the 19th century, ragtime, vaudeville, blues, gospel, minstrelsy, dance, theater, burlesque, and drag were all part of an African-American performance tradition that flourished along Indiana Avenue until urban displacement razed the last clubs in the 1970s. Yet history-makers uneasy with the heritage of racism and segregation routinely gravitate toward romantic accounts of music as a democratic space in the midst of a segregated world.

On December 5th 1921 the Indianapolis Star reported on police raids seeking to eliminate White guests from Archie Young’s cabaret.

Jazz is now celebrated as Hoosiers’ cultural patrimony, but jazz and life on the Avenue inspired decades of anxiety among city officials. Rather than nurture an “atmosphere of camaraderie,” ideologues were eager to patrol inter-racial leisure and morality along the Avenue and leery of music’s potential to subvert segregation. For instance, during a December 1921 raid on the Golden West Cabaret, police arrested White customers who “were found in the place listening to the jazz orchestra that plays the syncopated music, as it is only found on `de Avenoo.’” Prohibition had forced African-American entrepreneur Archie Young to transform his saloon at 532 ½ Indiana Avenue into a soda parlor known as the Golden West Cabaret, and jazz performers often played the club. In 1921 the Indianapolis Star complained that Young’s club was known to be “frequented by both colored and white persons who are seeking night life in Indianapolis.” The Indiana Daily Times reported that “orders were issued to put the lid on the `avenue’” because “of “fear that trouble may be the result of white persons visiting negro cafes and dance halls in the `black belt.’” Archie Young argued “there is no law under which the police can stop white persons from visiting the cabaret.” The Police agreed that “they are aware there is no law to prevent white persons from visiting the cabarets, but they contend they can take names and search those who are found there … until the white persons are eliminated.” Read the rest of this entry

Gates, Place, and Urban Heritage

The most prominent “gateway” to campus will be a 52′-tall column at the corner of West and Michigan Streets that is expected to be in place in Fall 2018 (click for a larger view).

This week Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) celebrated the impending construction of five “gateways” to campus, architectural features designed to identify the campus boundaries as students, staff, and visitors enter the near-Westside university. The most prominent gateway will be at West and Michigan Streets, a 52′-tall limestone and steel monolith that will be lit at night and be neighbored two blocks south by a more modest marker at New York and West Streets. Alongside these gateways a “series of landscape mounds along West Street between the two gateway markers also will visually distinguish the campus from the surrounding city.” This exercise in placemaking takes its aesthetic inspiration from the campus itself, invoking the architectural forms of the University Library (designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes, completed in 1994), Campus Center (SmithGroup JJR, 2008), and Eskenazi Hall (Browning Day Mullins Dierdorf, 2005). The gateways aspire to fashion a material landscape stylistically consistent with these existing buildings, though the media coverage of the gateways has featured the sheer scale of the monoliths, which are “large enough to be seen from an airplane.” Chancellor Nasser Paydar exalted that “anyone on a plane approaching Indianapolis, we want them to see this is how proud they are with this campus.” Read the rest of this entry

Race and the River: Swimming, Sewers, and Segregation

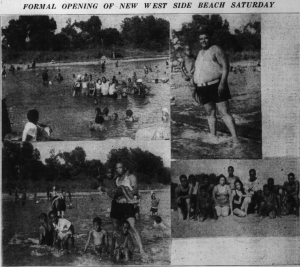

In August 1936 the Indianapolis Recorder included these images of the newly opened Belmont Park beach.

Last week Indianapolis’ tourism agency Visit Indy proposed building a beach along the White River, the waterway that meanders through the heart of Indiana’s capital city. The idea modeled on temporary beaches in Paris (where swimming is not allowed in the Seine) was greeted with some skepticism: today, much of the river has a well-deserved reputation for pollution reaching back over the last century. The river and its urban tributaries have long been fouled by combined sewer overflows, industrial discharges, and upriver farm wastes, and many stretches of the river are inaccessible and unappealing. The Indianapolis press seem unable to imagine the White River as a tourist spot with something akin to a beach, but the river has a rich history of waterfront leisure that has included beaches from Ravenswood and Broad Ripple south to the edges of present-day downtown. Some of the most polluted stretches of the White River also wind through predominately African-American neighborhoods and attest to how segregation shaped African Americans’ experience of the river.

In 1916 the Indianapolis News delivered an alarming report that the White River from Washington Street south “is devoid of natural fish life and birds.” Below the West Washington Street bridge the State Board of Health’s John C. Diggs pronounced the river “a malodorous, septic stream, bearing on its surface floating matter of sewage origin,” concluding that the river “was of the same character as ordinary household sewage.” Two years before he told the American Chemical Society conference that “White River is a comparatively small stream, yet it is used as a source of public water supply and sewage disposal for over 300,000 people.” The 1916 study had already recognized that certain stretches of the river were more polluted than others. At Broad Ripple “the river is free from floating matter or objectionable odor”; at Crow’s Nest just south of Broad Ripple “water is clear, free from floating matter”; and at Emrichsville Bridge (just south of the present-day 16th Street Bridge) the “water is clean but has a slightly weedy odor.” However, the African-American near Westside lay directly north of the industrial pollution wreaked by companies like the Kingan and Company meat packing plant, near which “the surface is a black scum” and “bubbles of gas rise to the surface.” Their neighbors Van Camps were responsible for “pieces of tomatoes…on the surface of the water.” Read the rest of this entry

Gardens in the Black City: Landscaping 20th-Century African America

In July, 1937 Louise Terry was married in the garden at her parents’ Indianapolis home, and her mother Mary Ellen and father Curtis were likely proud of their daughter and garden alike. In the days leading up to the nuptials the Indianapolis Recorder rhapsodized about the Terrys’ garden: “A beautiful rock garden and lily pond bordered with flowers of variegated hues against a background of Sabin Junipers, Oriental Golden Arbor-Vitae, Colorado Blue Spruce, Virginia Glanca, Blue Junipers, Japanese Cedars, and stately Poplars will create a celestial atmosphere … at the Terry residence, 1101 Stadium Drive.”

Dorothea Lange’s 1939 image of a North Carolina sharecropper’s cabin indicated “Note also flower garden protected by slender fence of lathes” (Farm Security Administration,Library of Congress).

The Terrys’ garden lay in the heart of the city’s near-Westside, part of an overwhelmingly African American neighborhood that was routinely caricatured as a “blighted” or “slum” landscape. In the summer of 1937 that Louise Terry was wed, construction was nearing completion on the city’s first major urban renewal project, Lockefield Garden, just blocks from the Terry home (the segregated African American community accepted its first tenants in February 1938). There was indeed genuine impoverishment and material hardship in much of the near-Westside, yet the African-American city was dotted with ornamental gardens like the Terrys’ home. The archaeological scholarship on African-American landscapes includes fascinating analyses of plantation spaces and food gardens, but there is far less scholarship on the scores of ornamental African-American gardens in 20th-century cities and suburbs. Compounding the dilemma in cities like Indianapolis is the reality that many of these gardens have been erased. Nevertheless, ignoring them allows racist stereotypes of longstanding urban ruin to pass unchallenged, and it risks ignoring that many similar gardens and gardeners remain scattered across the contemporary city. Read the rest of this entry