Dispossession and Demolition: Razing Second Christian Church

In February 1948 Second Christian Church celebrated its move into a 1910 church on West 29th Street and Kenwood Avenue. Second Christian would be one of the longest-lived Black congregations in Indianapolis, tracing its origins to 1866 when a mission church and then several houses of worship were located throughout the Black near-Westside. The North Park Christian Church had called the neighborhood home since its formation in 1897, and in August 1909 the congregation lay the cornerstone for a new brick church on West 29th Street, where North Park held their first services in January 1910. In the post-World War II period, though, the Black community was expanding north into formerly segregated white residential neighborhoods, which included the late-19th and early 20th century homes near the West 29th Street church.

The church remained in use until just two years ago, but this week the 112-year-old house of worship was razed. In a community close to downtown, steps away from the Children’s Museum, and surrounded by longstanding residences, predatory speculators are hopeful the otherwise-undervalued property will be profitably re-sold for development. The West 29th Street church was a material reminder of the neighborhood’s complex heritage along and across the color line, and the historicity of the church and its place-based heritage could well have been invoked in remodeling and redevelopment. Instead, the church has now been effaced to become a parking lot until speculators can profitably develop the property.

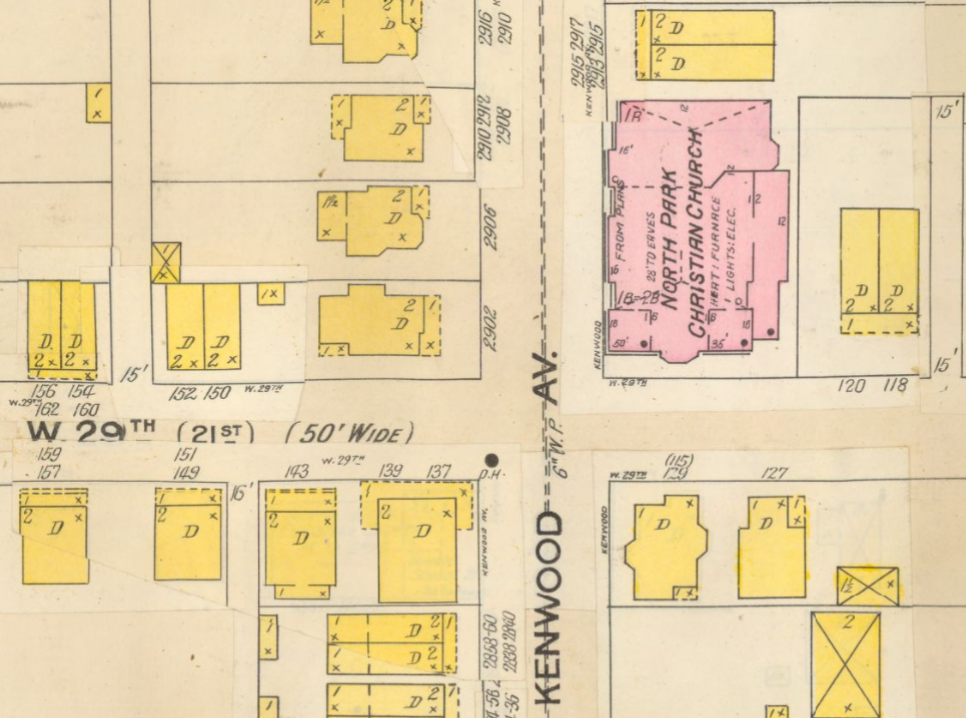

The location was first home to North Park Christian Church, which formed in June 1897 when 33 congregants initially met at Poole’s Hall at Illinois and West 30th Streets. The church elected Trustees in February 1898, and in March 1898 the congregation purchased a lot a block south for $700. Two months later they secured a building permit for a frame church they erected at the southwest corner of West 29th Street and Kenwood Avenue. Described by the Indianapolis Journal as a “suburban house of worship,” that frame church was dedicated in June 1898, when 72 people were members of the congregation. The Journal indicated the church was a “squatty” and “architecturally unique” structure with pink glass windows extending from floor to ceiling.

The surrounding neighborhood was predominately residential homes, and a scatter of businesses were located on North Illinois Street. By 1910 drug stores sat on opposite corners at the intersection of West 30th Street and North Illinois alongside an undertaker’s parlor and a series of stores with a police department station and fire house within a block. Frank Keegan, for instance, purchased the Hyde Park pharmacy on the northwest corner of Illinois and West 30th Streets in about 1893 and managed the store until retiring in 1919. Upstairs from his drug store was a dance and event space known as Mick’s Hall. James R. Phillippe owned a pharmacy on the other side of the street for 23 years; the Garrick Theatre sat on the east side of Illinois Street south of West 30th Street; and Alice Mendenhall managed a grocery store for 26 years at 3004 North Illinois Street until her death in 1924.

The growing North Park Christian Church laid the cornerstone for a new church on August 1, 1909 on the northeast corner of West 29th Street Street and Kenwood Avenue opposite their frame church, and the new church opened in January 1910 (compare 1909 update to 1898 Sanborn insurance map) The church was one of the earliest designs of architect Lewis Howard Sturges (1869-1941). Sturges was working in Illinois before 1900, and he came to Indianapolis in about 1906. Sturges designed a series of residential homes (e.g., 1919) and apartments (e.g., 1913) as well as retail architecture, and he designed a significant number of churches throughout Indiana. In addition to North Park Christian, in Indiana Sturges designed the Bethel Presbyterian (Knightstown, 1912), the Flora Indiana Christian Church (1913), Orleans Methodist Church (1914), First Baptist Church (Terre Haute, 1914), the Fowler Methodist Episcopal Church (1920), Milford’s Methodist Episcopal Church (1920), First Brethern Church (South Bend 1921), First Presbyterian Church (Winona Lake, 1923), Hope Presbyterian Church (South Bend, 1926), Tipton’s Presbyterian Church (1927), Ridgedale Presbyterian Church (South Bend, 1928), River Park Methodist Episcopal (South Bend, 1928), and Second Mt. Pleasant Baptist (Franklin, 1928); he also designed the Ashland, Ohio Christian Church in 1922.

The North Park Christian Church would eventually serve Black congregations for 80 years after World War II, but after World War I it sat in a segregated white neighborhood that vigorously resisted integration. In December 1920, for instance, School 36 on West 28th Street joined the Mapleton Civic Association and the Capitol Avenue Protective Association for an appearance before the School Board at which they asked “that the colored children in that district be sent to special schools.” By 1920 nearly all of the city’s public spaces and residential neighborhoods were segregated by practice, but the school segregation petition signaled a new ambition to create genuine legal codes restricting Black citizen rights. The Capitol Avenue Protective Association was a zealous advocate for residential segregation, and their President Ira Holmes appeared at the Mapleton Civic Association’s first meeting in May 1920. The new Mapleton neighborhood association elected as its first President Otto Deeds, whose wife Daisy was the President of the White Supremacy League. Holmes was a lawyer who represented Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson in his 1925 trial for the abduction, rape, and murder of an aide, Madge Oberholtzer.

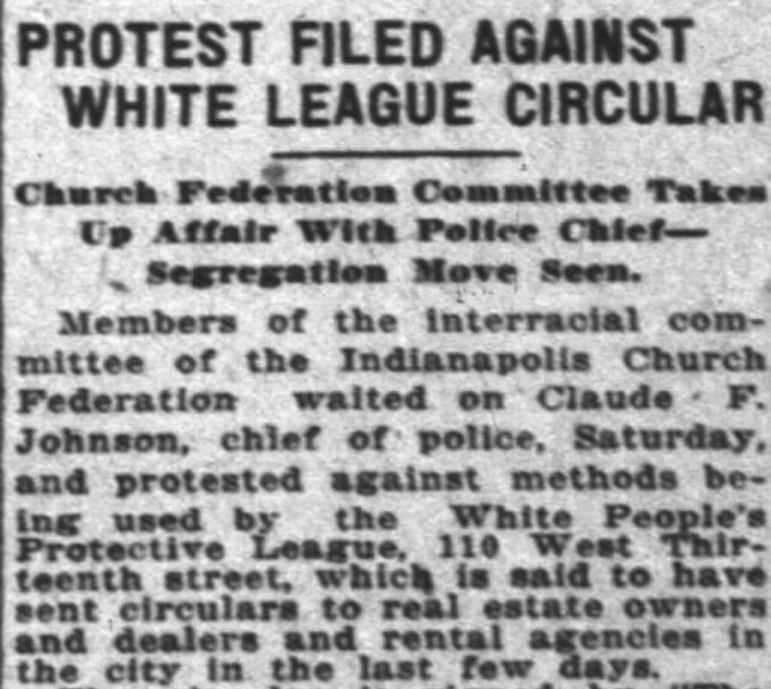

Much of the white city was similarly resistant to residential integration, forming neighborhood organizations focused on preserving racial segregation in neighborhoods like the one around the West 29th Street church. In January 1926, for instance, a group calling itself the White People’s Protective League became perhaps the city’s most vocal proponent for a residential segregation code, and all of the group’s officers lived within blocks of the West 29th Street church (though none appear to have been North Park congregants). The Protective League lobbied for a city code that would require a prospective resident to secure the written consent of the neighborhood’s racial majority before being permitted to move, and the ordinance passed in March 1926. Nevertheless, a nearly identical New Orleans law was struck down by the Supreme Court in March 1927, which rendered the Indianapolis law unconstitutional. In 1927 Black fire fighter William Goodwin and his wife Dona Hill Goodwin became perhaps the first Black residents in the neighborhood when they moved into a home at 501 West 29th Street. Their home was fire-bombed within a week, and neighbors unsuccessfully sued the Goodwins in October 1927 for deflating their property values.

On Easter Sunday 1926 the North Park Christian Church’s holiday address was delivered by the congregation’s most famous member, Governor Ed Jackson. Jackson presided over Indiana from 1925 to 1929, a period when the Ku Klux Klan was losing the grip it had held on political power in Indiana since 1923. Jackson was Indiana’s Secretary of State in 1920-1924 and was closely associated with the Klan’s leaders. Jackson was never confirmed to be a member of the hooded order, but as Secretary of State he lobbied Governor Warren McCray to support the Klan agenda. Jackson’s 1925 victory was dependent on courting the Klan’s interests, and when US Senator Samuel Ralston died in 1925 Jackson appointed a replacement approved by D.C. Stephenson. When Stephenson was convicted of the 1925 rape and murder of Madge Oberhaltzer he expected Jackson to pardon him. However, Jackson refused to pardon Stephenson, and the former Grand Dragon revealed his history of bribery of state officials including Jackson. Stephenson revealed that in 1923 Jackson had approached Governor McCray on behalf of Stephenson with a $10,000 bribe that McCray rebuffed. In 1927 Jackson was charged with bribery and stood trial while Governor, escaping with a hung jury in 1928. Jackson continued to teach the men’s Bible class at North Park after his term ended (his wife taught the women’s class). He was a Trustee for the church and continued as a congregant until he retired to his rural Orleans, Indiana farm in 1937.

In January 1930 North Park Christian Church united with the congregation of University Place Christian Church to become University Park Christian Church. The new congregation held its Sunday services at the West 29th Street church, but in the wake of World War II, the surrounding community rapidly became a predominately Black neighborhood. Second Christian Church was a Black church that traced its origins to March 1866, worshipping in a church at 11th Street and Lafayette Road that was reportedly “built out of lumber from an old Civil War barrack.” The congregation subsequently moved to two other churches in the predominately Black near-Westside, and they were worshipping at 13th and Missouri Streets when they laid a cornerstone for a new church at 9th and Camp Streets in May 1910. Henry Louis Herrod (1875-1935) became Second Christian’s Pastor when he came to Indianapolis in 1901, graduating from Butler University in 1903. Herrod became director of Flanner House in 1925 while directing Second Christian during a period of steady growth, and he remained Pastor until his death in 1935.

When the congregation purchased the West 29th Street church in 1948, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that the 227 of the 397 Second Christian congregants lived north of 16th Street. The neighborhood surrounding the church rapidly became a predominately Black community after the war. When the Indianapolis Community Plan committee of the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce mapped the “Distribution of Negroes in Indianapolis” in 1946, the neighborhood within a block of the West 49th Street church was identified as Black. The congregation expanded the church in 1974, and in 1977 under T. Garrett Benjamin Jr. the church counted over 1600 members. However, by 1977 the interstate had been built just blocks west of the church, displacing numerous postwar Black residents and destabilizing small businesses and churches near the church. The West 29th Street church was too small to accommodate the congregation, which had swelled to over 3000 members by 1982. In July 1982 the congregation moved to a church on East 38th Street that they reportedly purchased for $1.5 million. The congregation was renamed Light of the World Christian Church in 1984, and in 2002 they broke ground for a new church at 4646 Michigan Road that opened in July 2003.

Their former home on West 29th Street became home to New Liberty Missionary Baptist Church in July 1983, but they became the last congregation to worship in the 1910 church. In June 2019 the property was purchased by Brougher Plaza LLC. A demolition permit indicates the church was razed for parking, but it will almost certainly be targeted for development. The massive church might well have been remodeled and repurposed in ways that preserve the space’s rich heritage and use its very historicity as an attraction for potential residents, but the 112-year-old church was instead leveled. Emptying the lot effaces the neighborhood’s material heritage and renders it “placeless”: that is, the resulting non-descript parking lot is disconnected from any material traces of cultural heritage. Razing the church is dispossession that removes the public materiality of history, a maneuver that allows developers to imagine it as a “blank” space to build yet more interchangeable architecture.

Nazis in the Heartland: The German-American Bund in Indianapolis

On March 11, 1938 the Indianapolis Times‘ front page was dominated by reports that the German Wermarcht stood poised at the Austrian border, prepared to annex Austria into a “greater German Reich.” As Americans warily watched the Nazis’ expansion into Austria, the Times’ front page also reported on an Indianapolis meeting of an organization known as the German-American Bund (that is, Amerikadeutscher Volksbund). The organization of ethnic Germans was resolutely pro-Nazi, advocating American isolationism, repudiating communism, and voicing deeply anti-Semitic sentiments. Perhaps 25,000 Americans were members on the eve of World War II, and Indianapolis boosters hoped to swell membership with an appeal to “clean American nationalism against Communist international outlawry.” Indianapolis had a large German-American and German immigrant community since the 19th century, including a wave of Germans who migrated to the Midwest after World War I. However, the German-American Bund secured very few followers, and there was little sympathy for the cause. Indiana had a well-deserved reputation for xenophobia and white nationalism that is most clearly reflected in the Ku Klux Klan’s ascent to power just over a decade before the Nazis marched into Austria. The number of Hoosiers in league with the German-American Bund was certainly much smaller than the number of members of the hooded order in the early 1920s, but the Bund was committed to many of the same ideological issues as the Klan, and its history confirms the complex range of xenophobic sentiments that simmered in the 20th century Circle City.

The roots of the German-American Bund began in 1924, when the Free Society of Teutonia was formed in Detroit by brothers Fritz, Andreas, and Peter Gissibl. Fritz arrived in the United States in December 1923, and his brothers followed a month later. Hitler’s failed Munich Beer Hall putsch had occurred just a month before Fritz arrived in New York, but Fritz had no affiliation with the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (that is, the Nazis) until he joined the party in 1926, when the group’s name changed to the Nationalist Society of Teutonia. The group claimed 500 members in October 1932, when they became the Friends of the Hitler Movement. Three months later, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in January 1933.

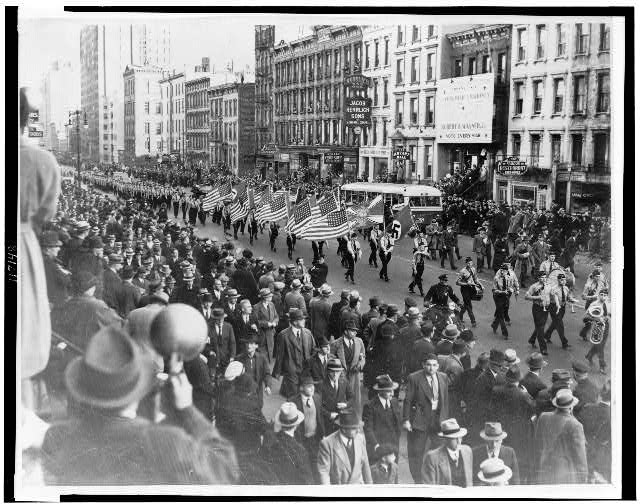

In May 1933 Nazi Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess approved the formation of an American organization to support the National Socialist cause. The Friends of the Hitler Movement was renamed the Friends of New Germany, and the group claimed it had 14 chapters in cities including Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and Cincinnati. The first evidence of Friends of the New Germany activism in Indiana came in November 1934, when the group sponsored a concert and flag dedication ceremony in Hammond, Indiana. Fritz Gissibl spoke to 500 people gathered in the Chicago suburb for the dedication of a US flag alongside “the flag of new Germany and that of the old empire.” In July 1935 in neighboring Calumet City the “boys auxiliary of the Friends of the New Germany of Chicago” appeared at an event at which 3500 people gathered for a parade at which “both the American and the German flags were raised.” A day later the Indianapolis Star was sufficiently unsettled by these Friends of the New Germany events to argue that the league “should be prohibited from using American soil for their political propaganda.”

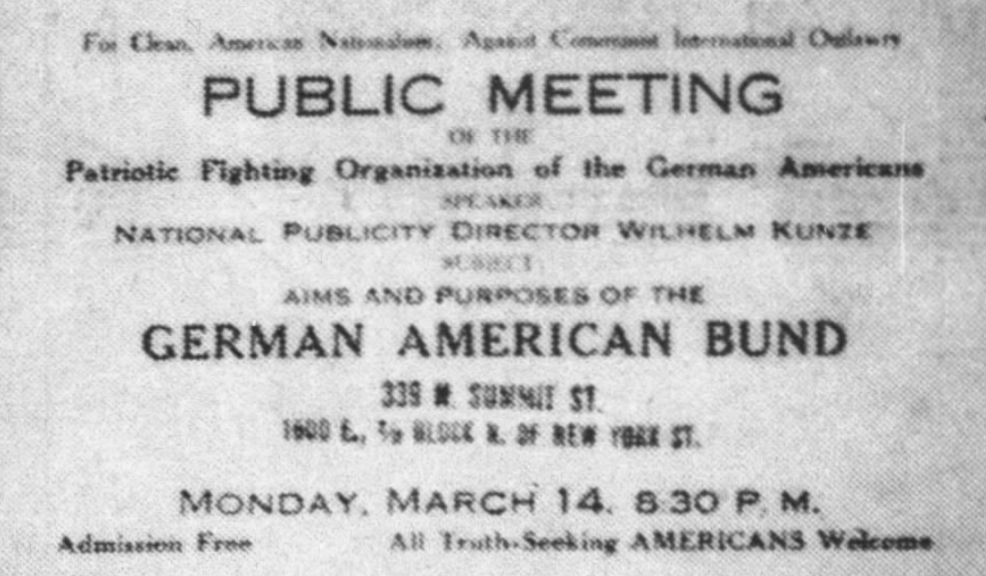

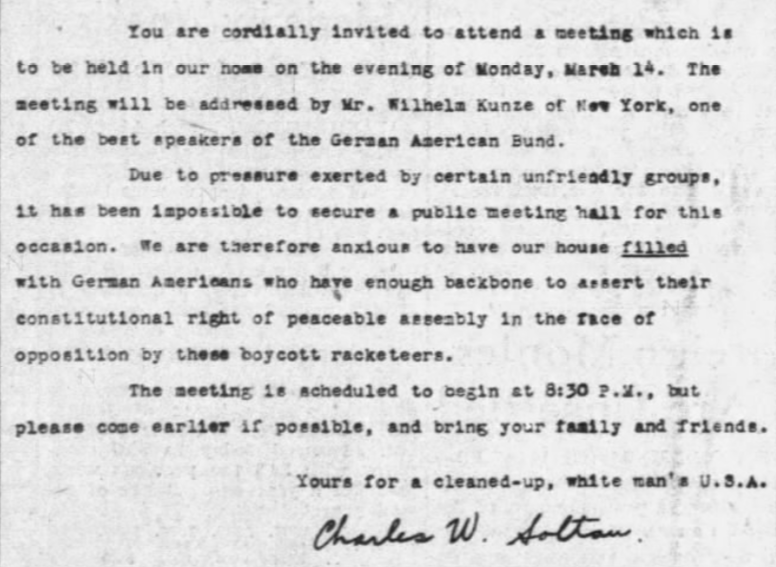

The organization became the German-American Bund in March 1936, with membership divided into three groups (known as Gaue). The Midwestern Gau included 19 local groups, and Indiana memberships had been established in Hammond, Gary, and South Bend. Those Bund memberships in northwest Indiana were especially active, and a 1938 Department of Justice investigation of the German-American Bund revealed that Hoosier members were gathering for pseudo-military training at a camp in Michigan (probably the camp that opened near Bridgman in June 1938). The Indianapolis Star reported that the group was “in disfavor” in Indianapolis and suggested that there had been “no effort to form” a chapter in the Circle City. However, on February 23rd it was reported that German-American Bund representatives were seeking a meeting hall in Indianapolis for a rally, and fliers had been distributed promoting a March 14 meeting at the Athenaeum. The fliers trumpeted the visit of Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze, the German-American Bund’s national public relations officer, who was touring the country on a recruitment drive. In January 1938 the Attorney General had announced the conclusions of an FBI investigation and cleared the Bund of any federal wrongdoing, and the emboldened Bund launched membership drives that included Kunze’s trip through the Midwest.

On February 23rd, Kunze appeared in Chicago at a rally that resulted in five arrests following a fight between uniformed Bund members and protestors, including two teenagers who refused to deliver the Nazi salute. This followed violence at a recruitment rally in Syracuse, where a group of American Legion veterans clashed with Kunze, who told the crowd that “The bund is organized to fight subversive influences in the United States. We want to make sure no small racial group gains control of the United States.” Fights likewise followed at a Kunze rally in Buffalo, where Legionnaires once again led the resistance to the Bund. Kunze then headed Midwest, speaking in Cleveland where he appeared “beneath two lighted swastikas and flanked by men wearing nazi belts.” He told a closed meeting that “the bund was against any and all atheism, against all subversive internationalism and against the indiscriminate mixture of Aryan and Asiatic or African races. `We want to preserve the culture in which America has been built and keep people of our own kind controlling the public mind.’”

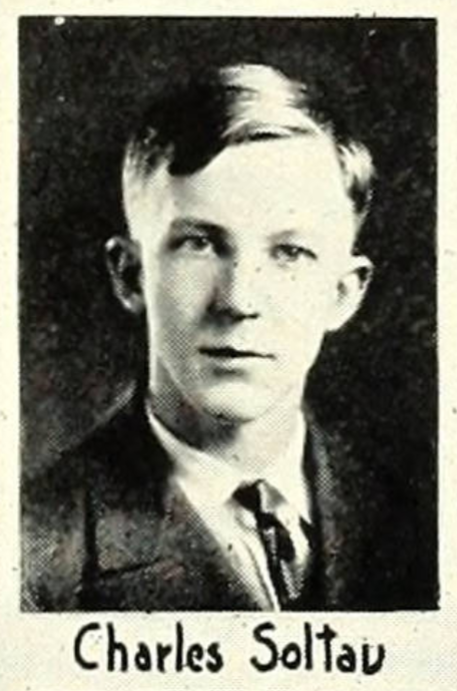

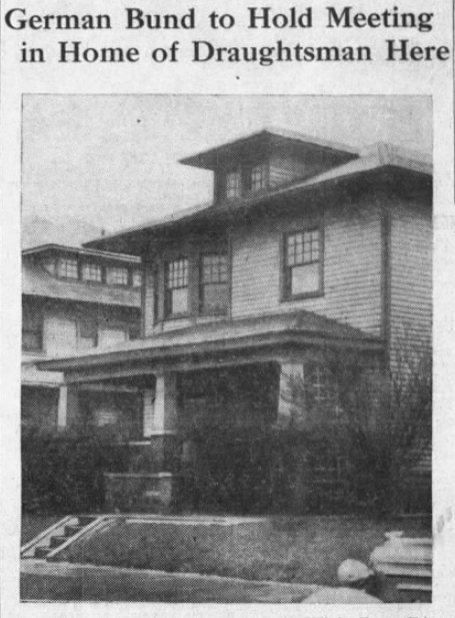

In Indianapolis, the Athenaeum hastily cancelled the Bund’s reservation; other Indianapolis meeting halls including the Liederkranz and Syrian-American Brotherhood had previously refused to host the event. The Indianapolis Star reported on February 25th that “an American-born Nazi agent” who was “born in Indiana” attempted to rent a hall “to organize Brown Shirt Nazi units in Indianapolis.” That local German-American Bund organizer was revealed to be Charles William Soltau, and Soltau, his father William Albert Soltau, mother Laura Hansing Soltau, and sisters Opal and Pearl resolved to hold the meeting at their own home on Summit Street on the near-Eastside. Charles Soltau wrote a letter to the Star that appeared on March 1st complaining that “the German-American Bund has been accused, maligned and condemned without a trial.” Soltau suggested that the Bund’s right to meet had been undermined by Jewish business interests, arguing that “a certain powerful minority group, which seems to have gained almost complete control of the press, fears the effect of public enlightment [sic].” A meeting invitation circulated announcing that the Soltau family was “anxious to have our house filled with German-Americans who have enough backbone to assert their constitutional right of peaceable assembly in the face of opposition by these boycott racketeers.” The invitation ended proclaiming “Yours for a cleaned-up, white man’s U.S.A.” alongside Charles Soltau’s signature.

Some Bund members were recent German immigrants bitter over their wartime loss and the Versailles treaty. The Soltau family, though, had lived in Indianapolis for more than a half-century by the time the German-American Bund gathered in their Summit Street home. John Albert Soltau (1847-1938) was born in Germany in 1847, migrating with his family to Minnesota in 1857 and then moving to Indianapolis in 1873. Soltau opened an Indianapolis grocery chain that eventually included 12 different stores. He was a Republican Ward delegate in 1894, and in 1902 he ran unsuccessfully for Marion County Recorder on the Prohibition ticket. In 1916 he was a delegate to the national Prohibition Party convention, and his long-term commitment to the temperance cause suggests he was socially conservative, but there is no particularly clear evidence for why his descendants would eventually embrace Nazi ideology. Some Prohibitionists allied themselves with the Klan’s cause in the 1920’s, and John Soltau’s brother James Garfield Soltau (1881-1932) was unmasked in 1923 as one of the first 12,208 Ku Klux Klan members in Indianapolis; nevertheless, there is no evidence any other family members joined the hooded order.

The oldest of John Soltau’s five sons, William Albert Soltau, was born in 1875. William worked in his father’s grocery stores and married Laura Hansing in June 1903. The family moved to 339 North Summit Street in 1916, by when they had two children Pearl (born 1905) and Charles William (1909); a third child, Opal, was born in 1920. William Albert Soltau became a real estate agent around 1924 and had his own real estate firm until his death in 1950.

Just a few days before Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze appeared at the Soltaus’ home in Indianapolis, the Indianapolis News suggested that the Soltau family had been quietly purchasing property in Brown County to create a German-American Bund camp. Bund camps including Camp Nordland in New Jersey and Camp Siegfried on Long Island were part of a network of camps where men, women, and youth exercised, received para-military training, and were steeped in Nazi ideology (Camp Nordland even hosted a joint Klan and Bund rally in 1940). The German-American Bund members in Hammond and Gary, Indiana opened a camp on Lake Michigan near Bridgman in June 1938, where Midwestern Bund members met until it closed in December 1941. By 1938 the Soltau family had assembled a tract east of Nashville near Gnaw Bone. Charles Soltau denied they planned to create a Bund camp at the site, and they had indeed been purchasing property well before the rise of the Bund, but it certainly was part of the Bund’s ambitions to expand the number of camps throughout the country.

A week before the planned Bund meeting the Indianapolis News ran a picture of the Soltau home on the front page of the newspaper, and two days before the meeting the Indianapolis Star reported that a neighbor indicated that “she was called on by a well-dressed young man carrying a brief case, who said that he represented the Bund.” Two days before the Kunze meeting Charles Soltau told the Indianapolis press that the meeting had been cancelled, but Kunze and a small circle of prospective members at their home on Monday March 14, 1938. After Kunze arrived Soltau called the police when protestors threw rocks through the home’s windows. The police arrived to find only seven people present and reported to the press that they found “a number of application forms for the Bund, several of which were filled out, and a number of German newspapers bearing Swastika emblems.” The substance of the Summit Street meeting was unreported, but two nights later Kunze held a recruitment meeting in a Dayton, Ohio hotel at which he referred to Jews “as `an atheistic international movement threatening the United States.’”

Despite the underwhelming Indianapolis recruitment session, the Soltau family remained committed to the cause. In November 1938, for instance, Charles William Soltau and his youngest sister Opal returned from a trip to Germany. The Bund held a series of trips to Germany to indoctrinate young members in Nazi ideology. For example, in April 1938 a party of 15 young men and 15 young women went to Germany on a trip that was paid for by the Bund. Realizing that the Bund was under surveillance by the FBI, the group was instructed not to board the ship together. Several days into that trip, though, they began to don their uniforms at midnight each evening and gather for marching and saluting drills (see pp. 65-71, FBI Report Section 10). When the group was in Germany they attended an event at Berlin’s Olympic Stadium in a section alongside Hitler’s box, which included Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, and Robert Ley. They met Goebbels afterward and attended a youth event at which Hitler spoke. The group spent six weeks at a Nazi youth camp near Storkow, which was a Hitler Youth camp between 1934 and 1945. Opal Soltau graduated from Arsenal Tech High School in 1938, but her brother Charles William Soltau was nearly 30, so she may have attended a German youth camp without her brother in tow. The siblings may simply have celebrated Opal’s graduation with a trip to Germany, but their connections to the German-American Bund make it likely the trip had links to the Bund. The brother and sister departed from Hamburg on November 3rd and arrived in New York on the 11th.

The Soltau family quietly supported the Bund cause. For instance, the A.V. Publishing Corporation (i.e., Amerika-Deutscher Volksbund) was a German-American Bund press incorporated in March 1937. A.V. Publishing printed the weekly newspaper The Free American (also known as Deutscher Weckruf und Beobachter and the Free American) as well as Nazi propaganda, including Mein Kampf and one of the most influential anti-Semitic tracts, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The press offered up 5000 shares of preferred stock at $10 a share in 1937, and a November 1941 FBI report identified William A. Soltau and each of his three children as four of 38 stockholders in the press (p.13 FBI Report Section 11). It is not clear when the Soltaus first invested in the press, but they were identified by the FBI as the only stockholders from Indiana. The Free American had local news columns for Fort Wayne and South Bend, but not Indianapolis.

The German-American Bund was at its height in 1938-1939, and in February 1939 20,000 people gathered for a German-American Bund rally at Madison Square Garden (the subject of the 2017 documentary A Night at the Garden). However, FBI investigations accelerated afterward, and New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia was fiercely anti-Nazi. He spearheaded a tax investigation that placed the Bund’s leader Fritz Julius Kuhn in jail in December, and Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze assumed leadership of the Bund. Kunze was ambitious to secure leadership of the organization, and he provided the New York District Attorney access to Bund accounting records knowing that Kuhn was guilty of graft.

The war began in September 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland, and the FBI and federal government stepped up its monitoring of the Bund. Kunze was detained by the South Bend Police on May 12, 1941, and in the inventory of materials confiscated by the Police was a series of index cards with seven Bund members’ addresses (pp.2-5, FBI Report Section 10). These included the Indianapolis address for William A. Soltau, the only Bund member from Indiana identified in Kunze’s papers. Kunze was soon accused of espionage, and in November 1941 he fled to Mexico, hoping to escape to Germany just a month before Pearl Harbor (he was captured by the United States in Mexico in June 1942 and spent the war in jail for espionage). The German-American Bund disbanded officially immediately after Pearl Harbor, but the federal government took aim on former Bund members throughout 1942. Some Bund members lost their American citizenship and were deported, but others were prosecuted for refusing to register for the draft. After draft registration began in September 1940 the Bund had instructed its members to resist registering for the draft, and when the draft began former Bund members began to be prosecuted for failure to register for the selective service.

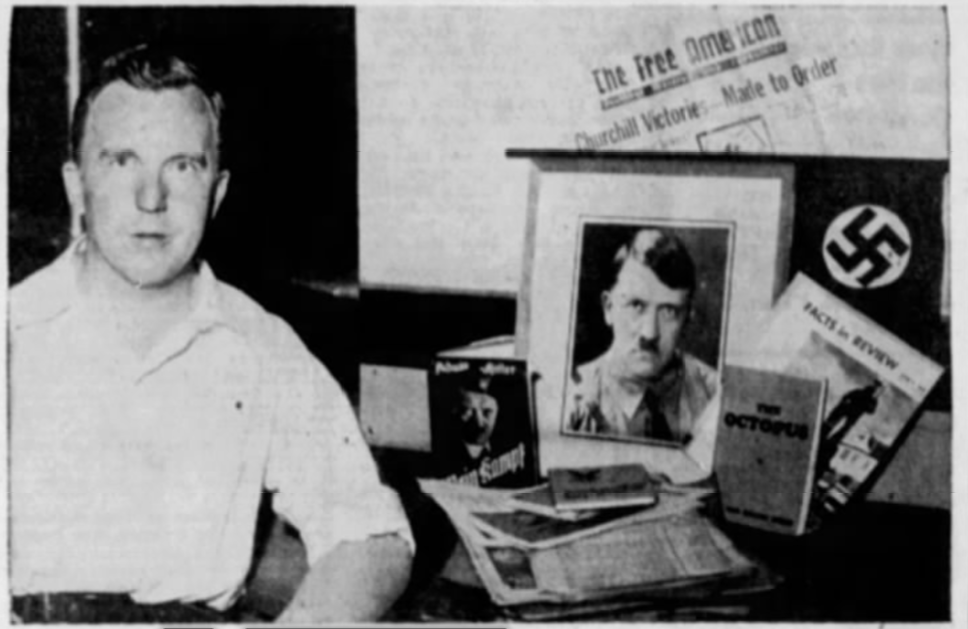

Charles William Soltau was among the former Bund members who refused to report for induction, and in August 1942 Soltau was arrested. US Marshals discovered an enormous volume of Nazi propaganda in the Soltau home including issues of The Free American, a portrait of Hitler, and Nazi banners. In a four-page letter to President Roosevelt Soltau argued that “in all my association with the German-American Bund I never was guilty of any subversive activity.” Soltau posted $5000 bond, but when he appeared in court in November he argued that “`My conscience will not permit me to bear arms against the German people.’” He informed the court that “`This war is a war of aggression by the United States against the Germans. I am a man of German blood and I don’t think it is right or fair or just for a man of German blood to bear arms against the German people.’” The jury deliberated just six minutes and delivered a five-year sentence to Soltau. Judge Robert C. Baltzell concluded that “I have never seen a more contemptuous fellow in this court,” and he resolved that “I am going to do all I can to see that you serve as much as possible.” While Soltau was serving his sentence in a federal prison in Milan, Michigan, his mother Laura Hansing Soltau died in December 1943. William Albert Soltau moved to a home on Woodlawn Avenue in about 1948, and he continued to sell real estate in Indianapolis and Brown County. His son Charles was released in 1946, and Charles moved with his sisters Opal and Pearl to their secluded Brown County property near Gnaw Bone. Their father died there in October 1950.

The Soltau siblings quietly lived together in Brown County for the remainder of their lives, and none of the three ever married. In May 1961 Indianapolis News columnist Myrtie Barker reported on goat dairies in Brown County, and one of the dairies, the Pleasant Valley Goat Farm, was a 200-acre farm managed by the three Soltau siblings. Barker reported that the Soltaus had purchased three goats in 1952 that had expanded to 44 head by 1961, and the family sold goat’s milk and yogurt in local farm markets. Pearl Soltau worked as an accountant and was preparing tax returns at the farm.

Pearl was 62 when she died at the Gnaw Bone farm in May 1968. Charles William Soltau died in July 1971, with an obituary identifying him as a member of the “German-American National Congress” (i.e., Deutsch-Amerikanischer National Kongress), a heritage group founded in 1959. The two oldest siblings betrayed no history of continued xenophobic activism after World War II, but the youngest of the three Soltau children, Opal, remained connected to unsettling political causes after her siblings’ deaths. In the 1980s Opal Soltau was accused of mailing propaganda authored by neo-Nazi Gary Lauck from the post office in Nashville. Lauck headed the National Socialist German Workers’ Party-Overseas Organization, which mailed neo-Nazi literature from its base in Lincoln, Nebraska. In 1996 Opal was identified as an associate of Lauck after he was arrested in Denmark and extradited to Germany. Lauck stood trial for distributing propaganda, and his lawyer argued in a German court that “one of the witnesses, Opal Soltau, sent the anti-Semitic literature that Lauck is charged with distributing in Germany”; however, the judge rejected that argument and determined that Lauck was the source of the neo-Nazi propaganda. Soltau sold 120 acres in Brown County in September 1996 and completed the transfer in January 1997, and she apparently moved to Nebraska around the time of that sale. On January 1, 1997 she became a Director for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party-Overseas Organization. Soltau died in Lincoln in August 2008.

The Indianapolis press was certainly correct that there was little sympathy for the Nazi cause on the eve of World War II, and many groups like the American Legion and the Jewish War Veterans took a firm stand against the Bund from the very beginning. Nevertheless, the German-American Bund voiced many xenophobic social sentiments that were quietly accepted by many Hoosiers. Opal Soltau’s apparent lifelong affection for Nazi ideology was perhaps distinctive, but there is little evidence that the Bund members or earlier Klansmen universally reconsidered their deeply held feelings when the organizations fell apart. We risk ignoring the persistence of such sentiments if we fixate on these organizations, focus on a few individual personalities. and ignore all of the everyday people who were in league with such groups socially and politically.

References

Leland Virgil Bell

1968 Anatomy of a Hate Movement: The German-American Bund, 1936-1941. PhD dissertation, West Virginia University.

Susan Canedy Clark

1987 America’s Nazis: The German-American Bund. PhD dissertation, Texas A&M University.

Sander A. Diamond

1970 The Years of Waiting: National Socialism in the United States, 1922–1933. American Jewish Historical Quarterly 59(3):256-271.

Federal Bureau of Investigation

1941 German-American Bund, Freedom of Information Release, Part 10.

1941 German-American Bund, Freedom of Information Release, Part 11.

James E. Geels

1975 The German-American Bund: Fifth Column or Deutschtum? Master’s Thesis, North Texas State University.

Bradley W. Hart

2018 Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States. St. Martin’s Publishing, New York.

Eliot A. Kopp

2010 Fritz Kuhn, “the American Fuehrer” and the rise and fall of the German-American Bund. Master’s Thesis, Florida Atlantic University.

Irwin Suall and David Lowe

1987 The hate movement today: A chronicle of violence and disarray. Terrorism 10(4):345-364. (subscription access)

Images

Charles William Soltau Arsenal Tech Yearbook 1926 image and Opal Soltau Arsenal Tech Yearbook 1938 image, Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library

German-American Bund Camp Siegfried Yaphank, New York ca 1938, FBI

German-American Bund Parade, New York City 30 October 1937, Library of Congress

German-American Bund Rally, Madison Square Garden February 1939, still from 1943 Department of Defense film “The Nazis Strike”

Commerce, Execution, and the Black Corpse: Injustice and Sherman Arp

On March 10, 1893 Sherman Arp stood before a crowd that had gathered at 5:35 AM to witness his execution in Centre, Alabama. Arp had been convicted of murdering George Pogue in 1891 and was sentenced to death for the carriage-maker’s murder. In the pre-dawn twilight Arp sang spirituals in the moments before he was hung with a rope that had dispatched seven Black men before Arp. Sherman Arp’s execution, the sale of his corpse, and the suggestion that Arp was hung with the same noose used in an 1888 lynching underscore the breadth of anti-Black injustice in late 19th-century America.

Sherman Arp was born in Georgia in about 1868 and by his own account went to Alabama in 1880, where he married in September 1885. Arp and his wife had two children when Sherman was charged with the July 1891 murder of George Pogue. The Coosa River News reported in July that Pogue had been ill and his “death had been expected sooner or later, from his diseased condition, but on inspection by Dr. Elliott it was found that Mr. Pogue had been foully murdered with an axe.” Initially the murder was reported as a robbery, but in October one account identified a Black “man engaged in illegal whiskey selling,” Will Cantrell, murdered Pogue “to prevent Pogue from reporting him.” Cantrell was arrested in Georgia in early October, but he had been released by October 23rd, when it was reported that Sherman Arp was one of five men who had conspired to rob and murder Pogue. Three Black men–Arp, Alf Glenn and Abe Dixon–had been identified as conspirators with a pair of white moonshiners, Alex Burkhalter and Green Leath. Newspaper reports provided contradictory accounts of Pogue’s murder, but Glenn and Dixon had apparently had no role in the crime at all; Arp reportedly indicated he killed the elderly man in a robbery instigated by Burkhalter and Leath while at the two moonshiners’ gunpoints.

Arp was captured in Rome, Georgia, and the Centre Alabama newspaper reported that the Rome Sheriff “refuses yet to give up Arp to the authorities here, as he (Arp) claims he fears lynching if brought into this section.” A day later, though, the Sheriff took Arp back to Cedar Bluff, Alabama, where he joined Glenn, Dixon, Burkhalter, and Leath; however, the judge released the other four and committed Arp to jail to await trial. As Arp feared, “Immediately upon the announcement of the decision, the large crowd which was present, made a dash for Arp and attempted to kill him, but Sheriff Blair and Deputy Angel drew their guns and stood the would be lynchers off, until the officers got the negro in a buggy and drove rapidly out of Cedar Bluff. The mob was unmasked and would have dealt short justice if they could have got their hands on Arp.”

In July 1892 Arp went to trial, and on July 29 he was found guilty of murder and it was “recommended that he be hanged by the neck until he is dead, dead! dead!” He was to be hung within the week, but Arp was spared by a state Supreme Court review. The State Supreme Court rejected Arp’s appeal on January 26, 1893 and set his execution for March 10. As Arp awaited his execution he was a witness in the February trial of Burkhalter and Leath, when the two accused conspirators were found innocent. A week after their trial Arp was being imprisoned in an unheated chicken coop where his feet and hands had suffered frostbite. By February 23rd he could hear the gallows being constructed in earshot of the jail cell he had been moved to in preparation for his execution. Arp did indeed go to the gallows on March 10th, with one witness declaring that “He was as game a human as ever stood upon scaffol [sic].”

Arp reputedly was hung by a “historic rope” owned by Floyd County, Georgia that had been used to hang seven other men before Arp. The Coosa River News reported that the “rope with which Arp was executed, was the instrument of seven hangings prior to its use upon Sherman. One of these was a lynching at Summerville, Ga.” It is not clear if Arp was indeed hung by the same rope used in previous murders or executions, but in May 1888 Henry Pope was lynched in Summerville, Georgia after being seized from the Chattooga County jail. Pope had been charged with rape, twice stood trial, and was convicted for a second time in March 1888. Pope was scheduled for execution in May, but five white citizens testified that Pope had not been at the scene of the rape, and he was given a reprieve by Georgia Governor John Brown Gordon. Hearing that news, a mob raided the jail on May 1, 1888 and hung Pope. Regardless of whether Arp had shared the same noose as Pope, the invocation of the lynching cast Arp’s own execution as part of a justice system that included lynching.

In perhaps the final dehumanization of Sherman Arp, he sold his body to a local physician. By most accounts he hawked his body by the pound. A Montgomery newspaper reported that in the week before his execution Arp informed local physicians he “desired to be weighed like a hog and sold by the pound” following an auction between those doctors. Of those physicians, “Dr. Will Darnell raised the bid to 8 cents per pound and the trade was closed. Arp went on a pair of scales and was weighed. He tipped the beam at 158 pounds. Dr. Darnell then figured up the amount and paid over to Arp $12.48 in cash and Arp gave the doctor an order for his body. Arp then proceeded to blow the money for good things to eat and drink and while it lasted he had a rousing big time.” However, one report a week later indicated that the auction tale was fictional and Arp had instead received a flat fee of $10. A week after Arp’s execution the newspaper provided an unsettling aside on masculinity and the Black corpse when it reported that “The physicians have been desecting [sic] Arp’s body since his execution. He was a well developed specimen of physical manhood.”

This narrative witnessing to Sherman Arp’s fate risks fixating only on the final tragic part of his life, but his story underscores the ways racism constrained and valued Black life. Exacting justice on Arp by inflicting frostbite before his execution—and then hawking his corpse for dissection—underscores the ways that racist justice was projected onto Black bodies. The fascination with the rope that had reputedly served as both hangman’s and lynchers’ noose reflected the ways execution and lynching were both accepted sentences in a racist justice system. In 1964, a historical account in Centre’s Cherokee County Herald confirmed the interchangeability of execution and lynching in historical memory. Clyde Walden Reed reminisced that “We had a few lynchings in those days, also hangings by court order. I remember when Sherman Arp was hanged Oct. 10, 1893 [sic].” Rather than suggest that Arp’s story is an aberration in the American experience, it instead is precisely the sort of dehumanizing indignity that racist injustice imposed on many now-anonymous targets even as it delivered an implicit warning to Black observers.

Retreating to Exclusivity: Diversity and Place at Newfields

In 1964 New York designer Edward Durell Stone advised the Art of Association of Indianapolis to move the John Herron Museum of Art from its location at 16th and Pennsylvania Streets. The Association managed the Herron Museum, and they hired Stone and a team of consultants to assess the expansion or renovation of their aging 1906 facility. Yet when Stone told a Columbia Club audience that the museum should be moved to the western edges of the Butler University campus, he was greeted with a chorus of complaints that revolved around museum access, equity, and urban preservation. One person complained “Should it be some mysterious privilege of a few people to make the cultural blessings of the arts less accessible to all the people? A museum should be a busy place, centrally located near public transportation, near office buildings, near schools, near hotels and meeting and eating places near all the people in our community.” This was perhaps idealistic, but it actually was not a new sentiment: when the museum was dedicated in November 1906 a speaker argued that “an art museum should be an institution for the masses rather than for the classes.”

Now part of a complex renamed Newfields, the Museum is today struggling with equity and inclusion challenges that are certainly rooted in its institutional culture and common to many other art museums. Nevertheless, the institution’s 21st-century exclusivity also reflects the heritage of the landscape where the museum sits today. Today Newfields is located in what was an elite White area throughout the 20th century, not far from the location Edward Durell Stone advocated in 1964. Nevertheless, predominately working-class and middle-class African-American neighborhoods sit in walking distance of the museum campus. The contemporary experience of Newfields and the perception of its exclusivity is shaped by a broad range of factors, but it is firmly based in its own place-based heritage. A sober assessment of that landscape history should be an essential dimension of Newfields’ ambitions to be an inclusive museum.

Edward Durell Stone’s 1964 proposal came in the midst of rapid suburban growth, highway construction, and urban displacement, and those dramatic transformations in class, color, and place intersected with planning for the museum. Stone’s favored location was in the 4600 block of Michigan Road, which in 1964 was the home of executive Samuel M. Harrell (today it is a private residential compound). Today most observers would consider that location to be the heart of the city, but in 1964 one critic argued that “The suggested move of our art museum to the fringes of suburbia seems to be anachronism, completely out of context with the spirit of our times.” Another observer questioned moving the museum north of 30th or 38th Streets, arteries that still lingered as residential redlining boundaries between White neighborhoods to the north and Black neighborhoods to the south: “Must the city be divided with 30th or 38th the Mason-Dixon Line, below which the urban untouchables live? Our art museum must be for the people and easily accessible to all. It should be readily available to inspire those in need of contact and familiarity with art and beauty.”

Resistance to moving the museum was dismissed in November 1966, when the family of Josiah K. Lilly, Jr. donated the Oldfields mansion and grounds to the Art Association of Indianapolis for the former Herron museum. In November 1968 the Art Association announced it would soon begin building the new museum, which became the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 1969. The Indianapolis Star once again enthusiastically championed the museum as a community institution, declaring that “the new art center will not be exclusive territory for artists. Everyone will be encouraged to participate in museum activities. The art center will be truly a community affair.”

Despite such rhetoric, for much of its recent past the museum has struggled to turn the exceptional collections and surrounding grounds into an inclusive place (compare Ben Valentine’s 2013 assessment of the IMA’s shifting mission). After seven years of free general admission, in 2014 the museum instituted an admission fee “to maintain long-term financial stability,” and free admission to the grounds and bike access ended in 2015. In 2017 the museum rebranded itself as “Newfields,” referring to the whole complex of buildings and gardens on the museum grounds. Perhaps the most unsettling moment came in July 2020, when curator Kelli Morgan left the museum after labeling it a “toxic” working environment and questioning the institution’s commitment to inclusivity. Morgan wrote after her resignation that through “very deliberately racist and sexist practices of acquisition, deaccession, exhibition and art historical analysis, museums have decisively produced the very state of exclusion that publicly engaged art historians and curators like me are currently working hard to dismantle.” In February 2021 the museum came under renewed criticism when it posted a job notice seeking a candidate who would “attract a broader and more diverse audience while maintaining the Museum’s traditional, core, white art audience.” That clumsy admission of the museum’s racial homogeneity fueled a response by 85 staff members advocating assertive partnerships with diverse community constituencies and seeking the resignation of the museum’s director. The director desperately reaffirmed the museum’s “core commitment to inclusion,” but he resigned a few days later.

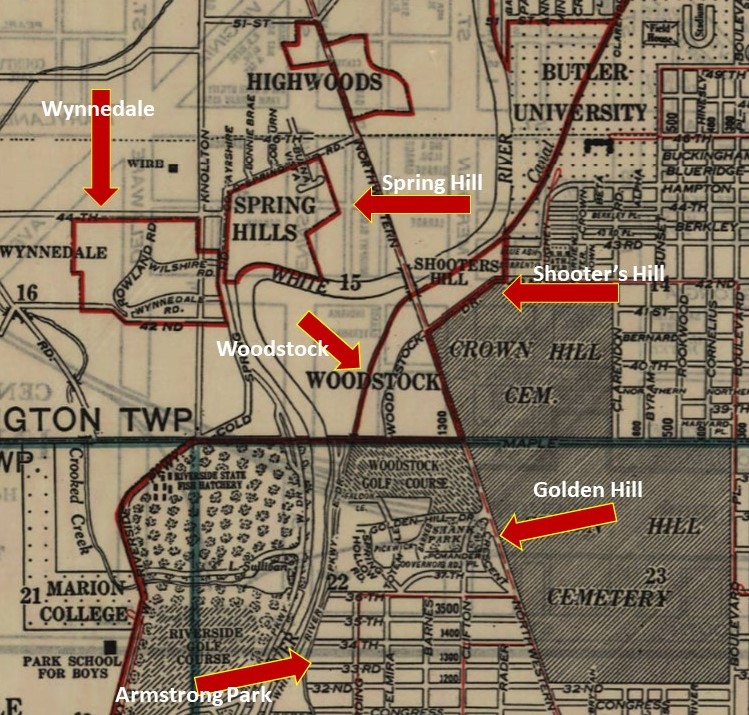

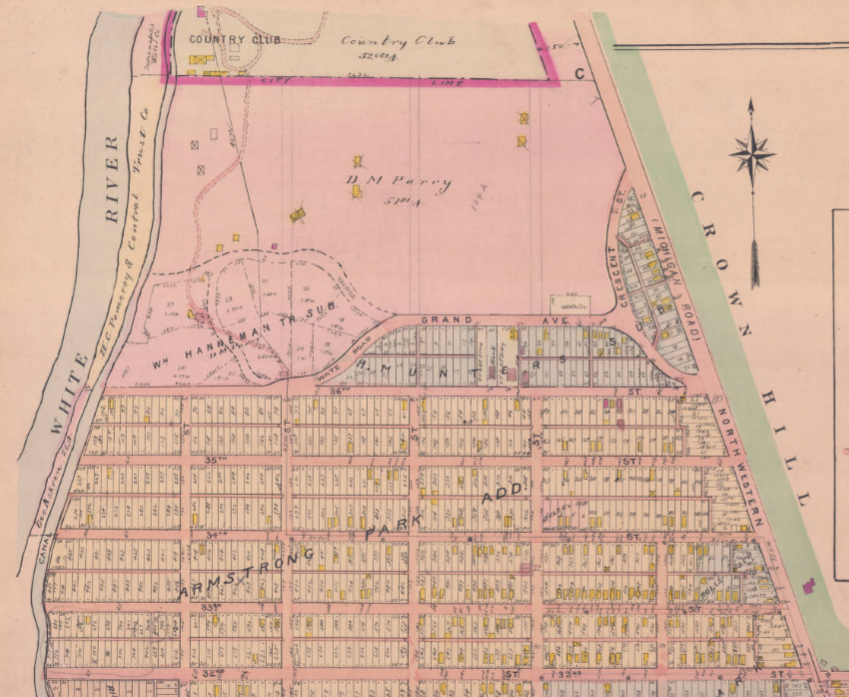

In the early 20th century the future museum grounds rapidly became an exceptionally affluent community at the margins of the city. Perhaps the first seed was planted at the end of the 19th century when the Indianapolis Country Club opened on the south side of Maple Road (now 38th Street). The club included the city’s most wealthy families, and when the first clubhouse was dedicated in November 1891, the Indianapolis Journal reported that there “was an unusual display of elegant diamonds, nearly every one’s costume being resplendent with these gems.” Indianapolis’ high White society gathered at the club for 20 years for golf, tennis, bowling, dancing, and fine food. The Country Club decided to move west of the city in 1912 (where it remains today), and Linnaes C. Boyd, Hugh McKennan Landon, Louis Cass Huesmann, and Arthur V. Brown purchased the roughly 48-acre property for $48,000. They initially planned to build “a high class residence district” (or a “preparatory school for boys”) on the tract that neighbored Hugh and Suzette Landon’s own home to the north. Today known as Oldfields, Landon’s home was built between 1911 and 1913 in an area that became known as Woodstock, and in 1932 the Landon home was purchased by Josiah K. Lilly, Jr.

After the Indianapolis Country Club moved west, the property became the new Woodstock Club, which was incorporated in May 1915. Woodstock was incorporated as a town in November 1920, with just seven families living on 48 acres. Shooter’s Hill sat just east of Woodstock, and like Woodstock it was a very small and elite community. When Shooter’s Hill incorporated as a town in November 1925, it had just 14 residents, and in 1935 there were just three estates in the town. This pattern of affluent and small enclaves was repeated a series of times in the surrounding area: in July 1927, for instance, Crow’s Nest would file to become the 10th incorporated town in Indianapolis, a list that eventually included Spring Hills (incorporated in 1927 near Cold Spring and Michigan Roads) and Wynnedale (incorporated in March 1939, along Cold Spring Road on the west banks of the White River). Nearly all of these incorporated towns were composed of a handful of quite affluent residents: in 1940, for instance, the census recorded 19 people living in four households in Shooter’s Hill, including three people identified as servants, two as maids, and one as a houseman; a fourth household was a gardener, his wife, and two children renting one of the four residences, so there were essentially nine residents in three homes being served by 10 on-site laborers. The homes in Shooter’s Hill were purchased along with the complete 22-acre town by Christian Theological Seminary in 1963.

Oldfields was probably the most palatial home in the adjoining neighborhoods, and Golden Hill had the largest residential community. The Woodstock Club sat just north of Golden Hill, which had been a sparsely settled late-19th century resort spot. In October 1872, property began to be offered on a new subdivision marketed as “Clifton on the River,” but by June 1877 the area was being referred to as Golden Hill. In June 1879, for instance, a church picnic drew about 700 people to Golden Hill, and the Indianapolis News concluded that “No other place in this vicinity combines more of beauty and advantage than Golden Hill.” In April 1896 the Indianapolis Journal indicated that “Golden Hill has been one of the more popular picnic spots near here for many years,” reflecting that Golden Hill remained almost completely unsettled until the very end of the 19th century (the oldest home still standing in Golden Hill was built in about 1895).

In April 1892 John C. Shaffer purchased Golden Hill property adjoining the country club with plans to build a country estate, but in 1900 he sold his undeveloped tract to David M. Parry, who gradually purchased most of Golden Hill to create a family estate. Parry finished his Golden Hill home in 1904. Most of the streetscape and landscape planning in Golden Hill was done by Scottish immigrant George MacDougall, who landscaped Parry’s estate grounds beginning in 1908. After Parry’s death in 1915 his family hired MacDougall to plan the subdivision around Parry’s home; MacDougall also designed Stoughton Fletcher’s “Laurel Hall” estate, the streetscape for Woodstock in 1909, the Hugh McKennan Landon estate “Alverna” off Spring Mill Road, and the Nicholas and Marguerite Lilly Noyes home “Lane’s End” in Crow’s Nest.

In 1914 Parry and his family sold roughly 80 acres of Golden Hill to Arthur V. Brown, who planned to build “suburban homes,” and in September prospective residents were invited to visit the planned community. In April 1915 170 lots in the subdivision went on sale, and David Parry died just a month late. Lots sold relatively rapidly, with house construction occurring in the 1920’s and into the mid-1930’s by many of Indianapolis’ most noted architects. The Golden Hill Historic District now includes 54 residences.

The affluence of the neighborhood is suggested by the density of live-in service staff in the Golden Hill homes: in 1940, for instance, 15 live-in servants (and one nurse) were residents of Golden Hill in 13 different homes. Like all residential neighborhoods in the city, Golden Hill was racially segregated, though some of the elite estates were supported by live-in African-American service laborers. In 1910, for instance, John and Belle Kuykendall were living at 1306 West 36th Street in a home on David Parry’s estate, where John was working as a butler for Parry. The Kuykendalls moved out in about 1913, and only a handful of other Black service laborers would live in the neighborhood until after World War II. When the Home Owners Loan Corporation executed its residential security map for Indianapolis in 1937, Golden Hill was described as “Attractive location for property known as `small estates,’ yet not far from city center,” with no foreign-born or Black residents.

Golden Hill’s southern border is 36th Street, and south of 36th Street is now a neighborhood of predominately vernacular residences, most of which was originally known as the Armstrong Park Addition. Originally the home of the Armstrong family farm along Northwestern Street (i.e., Martin Luther King, Jr. Street), in May 1892 James Armstrong appealed to the Citizens Street Railway stockholders to improve streetcar access to his family’s newly opened park in north Indianapolis. Armstrong pled to the streetcar company that “With the help of the company I intend to make Armstrong Park the most attractive spot around Indianapolis. A large sum of money is to be spent in making it a beautiful place. Nature has made it the most desirable spot for a park around Indianapolis. … It is to be made a place where the best people of Indianapolis will go.” The Park invited urbanites to take the streetcar to Armstrong Park for picnicking, food, concerts, and boating, and church groups and even healers held meetings in the Park, but in June 1900 northside residents filed an injunction against public drunkenness in the park. In September investors tried to sell the whole tract as one property, but in October 1900 the Armstrong Park Land Company began to subdivide the tract into residential lots. The Indianapolis News reported in May 1901 that 550 of 689 lots had been sold, though most were purchased by real estate speculators and there was very little immediate construction. Five years later the News reported that 105 homes had been built in 1904, but about 40 families were living in tents on lots for which they had not completed payments. In 1908 the addition remained relatively sparsely settled, but by 1916 it had become relatively densely populated.

The neighborhood was quite densely populated in 1940, but there was not a single Black household in the neighborhood (though a Black family was settled at 3732 Northwestern Street). A few African-American residents had begun to settle homes immediately south of Armstrong Park, though, and the 1937 Home Owners Loan Corporation “redlining” map rated the neighborhood “definitely declining.” That “decline” was certainly based on the apparent “Encroachment of inharmonious groups (negro)” and the “Possibility of negro purchasers from territory south of 30th street.” The neighborhood began to include Black residents in the early 1950s, with sales notices for homes appearing in the Indianapolis Recorder by 1954.

The Armstrong Park neighborhood was overwhelmingly African American by the time the northwestside was targeted for construction of the northwest leg of Interstate-65. A plan for the route for I-65 through the near-Northside was proposed by engineers in January 1960, and surveying had begun by 1961. Residents of both Golden Hill and the African-American neighborhoods to their south were already contesting the highway plan in September 1959, when the highway department met with community. However, an engineer dismissed resistance and told the audience that “If the expressway is not built `Indianapolis will be a dying city. You can’t make a cake without breaking eggs … If it is so bad you can’t stand it, you’ll just have to move.’” The Indianapolis Recorder had already bitterly concluded in 1961 that “The battle is lost. Many Northside residents who, earlier last year, tried in vain to get Interstate 65 built anywhere except on the route proposed by the State Highway Department, are chiefly concerned now with the relocation and depreciation value of their homes.” In July 1963 the planned route from 38th Street south to 16th Street was expanded from four to six lanes, and in April 1964 Indianapolis Recorder article outlined the favored path for the interstate, crossing White River just south of Golden Hill at roughly 36th Street. In September 1966 a city planner acknowledged that the proposed Interstate-65 pathway bent around Golden Hill but cut through Armstrong Park, admitting “that Golden Hill is white and that these neighborhoods are Negro. The idea is prevalent in these neighborhoods that the route has more to do with race than with cost. … Another idea prevalent in these neighborhoods is that the projects are planned and scheduled to benefit the slum landlords” (who were profiting from re-housing displaced residents in very poorly maintained homes).

The most prominent voice against the highway came from Golden Hill resident Alan Clowes, who formed a group known as Livable Indianapolis for Everybody (LIFE) opposing the interstate. Clowes formed LIFE in December 1964 and lobbied against the interstate, calling the elevated roadway a “`Chinese wall of dirt’ which will do untold harm to this city’s future.” LIFE favored a northwest leg that ran along the western banks of the White River, cutting through Municipal Gardens and Belmont Parks, a route that would completely bypass Golden Hill and Armstrong Park. Clowes appealed to the Greater Indianapolis Progress Committee, a community advisory group that Mayor John Barton formed in December 1964. In June 1965, though, GIPC backed the proposed interstate plan, joining the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce and rejecting Clowes’ case for a different route or a below grade (a.k.a., “depressed”) interstate. By 1966 houses were beginning to be sold in the highway’s path through 31st through 36th Streets, a path that bisected Armstrong Park and the neighborhoods north of 30th Street; the interstate path would cut the formerly contiguous neighborhood into two sections separated by the elevated roadway.

In 1964 one critic of the plan to move the Herron Art Museum presciently predicted the transformation of conventional art museums beyond traditional gallery fare. He lamented that “An art museum on Michigan Road would degenerate into a place of weekend diversion rather than function as a place to see paintings.” Nearly the same argument was made in 2019 by Bill Watts, who complained that the renamed Newfields had shifted its focus from the arts to “curated outdoor experiences,” like putt-putt golf and holiday light shows. Newfields has perhaps insulated itself by restricting access to the grounds, imposing a steep admission fee, and focusing much of its programming on bourgeois suburbanites, and what may be most disappointing is that these shifts effectively retreat to the area’s 20th-century heritage of White elite exclusivity. The museum’s ability to fulfill its century-long commitment to serve a breadth of the city and embrace a diverse expressive culture is of course dependent on institutional transformations. Nevertheless, much of the story of the museum’s heritage is rooted in place-based exclusivity and requires Newfields develop a rigorous consciousness of their own landscape.

Sources

David Alan Ripple

1975 History of the Interstate System in Indiana: Volume 3, Part 1 – Chapter VI: Route History. Publication FHWA/IN/JHRP-75/28-1. Joint Highway Research Project, Indiana Department of Transportation and Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

Trent Spence

1996 Nicholas H. Noyes: An Historic Landscape Master Plan, Indianapolis, Indiana. Landscape Architecture Thesis, Ball State University.

Bradley D. Vogelsmeier

2013 Upper Class Enclave Identity: A Case Study of the Golden Hill Community. Undergraduate Honor’s Thesis, Butler University.

Images

Indianapolis Baist Atlas Plan # 33, 1908 Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection IUPUI University Library

Indianapolis Baist Atlas Plan # 33, 1916 Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection IUPUI University Library

Indianapolis George F. Cram Company, Inc., 1945. Historic Indiana Maps IUPUI University Library.

Oldfields, Indiana Landmarks H. Roll McLaughlin Collection, IUPUI University Library.

Parry Mansion in Golden Hill, from scrapbook created by librarian Alice K. Griffith, circa 1910-1920, Indianapolis Special Collections Room, Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library

Circle City Confederates: Family and Rebellion in Civil War Indianapolis

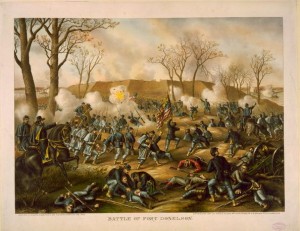

This circa 1887 chromolithograph captured the Union victory at Fort Donelson (Library of Congress).

On February 16, 1862 the Union Army captured more than 7000 Confederates at Fort Donelson, Tennessee. Many of the Confederates were serving in the First Kentucky Brigade, the largest Confederate unit recruited from Kentucky, and about 3700 of the captured rebels were escorted to Indianapolis to be held in the newly opened Camp Morton prisoner of war camp. There were numerous Hoosiers who had Southern sympathies or had even sided with the rebellion, and some of the captured Confederates actually knew Indianapolis quite well. Greenup B. Orr, for instance, was born in Kentucky in about 1826 and served in the Fifth Indiana Volunteers during the Mexican-American War. Orr enlisted in Madison, Indiana in October 1847, served in Company F in Mexico, and mustered out in July 1848. He returned to Gallatin, Kentucky, where he was living in 1850 and married a year later in March 1851. By 1855 Orr had moved to Indianapolis and was working as a brick mason at the corner of Indiana Avenue and Tennessee Street (now Capitol).

Greenup Orr was still living in Indianapolis on the eve of the war in 1860, but as Orr’s neighbors began to enlist for the Union cause, Orr traveled to Camp Boone Tennessee, where the 35-year-old joined the Confederacy’s 2nd Regiment Kentucky Infantry on July 13, 1861. The 2nd Kentucky Infantry was organized in July 1861 at Camp Boone, so Orr was among its earliest volunteers. Orr was joined by Indianapolis resident Alfred (Alf) McFall, who volunteered the same day as Orr. McFall was born in about 1838 in Ohio, and in 1850 the 12-year old was living in Indianapolis with his mother Ann, older sister Margaret (age 14), and brothers George (10), William (8), and Oscar (5). It is not clear where the McFalls were living in 1850, but Ann was listed in the 1857 Indianapolis City Directory living on Market Street between East and Liberty Streets. Read the rest of this entry

Dehumanization, Dignity, and Development: Contemporary Cemetery Preservation

In July 1905, Martha Spinks was buried at the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane, laid to rest among hundreds of patients to die at the hospital since it opened in 1848. Like many of the men and women treated in the hospital, Spinks’ story has been forgotten as she quietly rested on the grounds of what became known as Central State Hospital and eventually closed in 1994. Spinks was among the last patients to be buried on the grounds of the hospital, which indicated in 1908 that 4,704 patients had died since the hospital opened in 1848. If patients’ bodies were not claimed by their families they were buried in the northwest corner of the hospital grounds, and some were used for medical training. In 1889 the Hospital’s yearly report announced that the administration planned to place posts with the name of each deceased patient at the head of their grave, but this plan does not appear to have been systematically followed. In the early 20th century patients began to be buried at the neighboring Mt. Jackson Cemetery, with the last burial on the hospital grounds around 1905 but perhaps as late as August 1909. Read the rest of this entry

The “Blank Slate” of Pastness and African-American Place

Contemporary planners, developers, and proponents of 21st-century city life routinely celebrate cities’ historicity. Urban boosters extol the appeals of historical architecture, and where that historic built environment has been destroyed those urban champions applaud new designs inspired by local architectural heritage. Few neighborhoods would seem to lay a stronger claim on such history than Indianapolis’ Indiana Avenue. Home to residences as early as the 1820s, the Avenue became a predominately African-American business and leisure district at the outset of the 20th century only to witness postwar urban renewal projects that razed nearly all of the stores, clubs, and homes along the Avenue.

Last week a Development Project Manager for Buckingham Companies enthused about the developer’s proposal to build a 345-unit five-story apartment complex in the 700 block of Indiana Avenue, calling the site a “blank slate.” The parking lot and an undistinguished 1989 office building on the site indeed reflect none of the Avenue’s rich heritage. The asphalt parking lots and a functional but forgettable office building are yet more evidence of the city’s historical uneasiness with appearing to deter development after they had been vocal advocates for extensive urban displacement projects, Indiana University’s establishment and growth, and highway construction that collectively depopulated the predominately African-American near-Westside. American urban planners launched numerous similar projects after World War II that targeted African-American communities under the guide of slum clearance or community renewal, uprooting residents and then razing much of the Black urban landscape. These postwar planners hoped to build new cities, launching a host of ideologues’ fantasies for a reimagined city that would serve segregated White suburbanites who would work, play, and shop in the urban core. Read the rest of this entry

Disenfranchised Design: Development and African-American Placemaking on Indiana Avenue

A 1950’s view of the 700 block of Indiana Avenue (image O. James Fox Collection, Indiana Historical Society, click for expanded view).

In January 1968 a group of African-American entrepreneurs and community activists gathered in the Walker Theater with the Director of the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission to determine the future of Indiana Avenue. Alarmed by the decline of the businesses along the historically African-American Avenue and frustrated by their inability to defy urban renewal projects, the group hoped to encourage investment in Avenue enterprises. Advocating strategies that have since become common in placemaking discourses, entrepreneurs had ambitious plans championing “a renewed civic and business vitality in the area of Indiana Avenue.” Their proposals included promoting cultural tourism focusing on the Avenue’s jazz history, proposing to create “a `Bourbon Street’ type entertainment and shop section … in the fashion of New Orleans’ famed `Bourbon Street’ long a mecca of Dixieland jazz.”

Yet business people were justifiably reluctant to invest their own capital because of the unpredictable effects of “slum clearance” displacements, highway construction, and the growth of the joint Indiana University and Purdue University campus that became IUPUI. The Indianapolis Recorder soberly reported on the absence of funding for such development, noting that “insurance and loans are virtually impossible for business-men on Indiana Avenue to secure since this section is considered a `high risk’ area.” The certainty of more renewal projects led one Avenue businessman to complain that “`We’ve seen from past experience that when these people come and take your property they pay as little as possible. I just can’t see how we could recover the money we might spend to fix up the area.’” Read the rest of this entry

Escaping the Noose: A Near-Lynching in Late-19th Century Boone County

An 1878 illustration of the Boone County Courthouse where Frank Hall was tried in 1894 (image Historic Indiana Atlas Collection, IUPUI)

On the morning of February 5, 1894 a crowd “of seven hundred or more Boone county farmers struggled and battled fiercely in the courthouse yard” in Lebanon Indiana eager to exact justice against Frank Hall. The 22-year-old African American was being held in the Boone County jail accused of an assault on a White woman on the evening of February 3rd. Hall protested that he had been at a watch raffle with scores of witnesses at the time of the assault, but the Sheriff arrested Hall the next morning and brought him to the jail. A crowd instantly gathered intent on hanging him, and as Hall was taken from the jail to the adjoining Courthouse the crowd got him in the noose three times. Hall and the Sheriff fought them off each time, and when Hall reached the Courthouse he was half-conscious, bloodied by the mob’s assault, and “several chokings had given his skin the purple hue of a grape.” Hall hastily agreed with the Prosecutor “to enter a plea of guilty and take the maximum penalty of the law for such offenses, twenty-one years in prison. He was afraid that he would be taken from jail and summarily executed.” Read the rest of this entry

Memory-Making and Civility: Removing the Garfield Park Confederate Monument

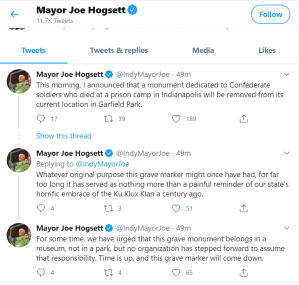

Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett announced his plan to remove the Garfield Park monument on twitter on June 4th, and it had been dismantled by the end of the day on June 8th (click for a larger image).

Last week in the midst of protests against racially motivated police violence, Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett somewhat surprisingly announced that the city would remove a 1909 Confederate monument in Garfield Park. In a series of tweets Hogsett indicated that “The grave monument was commissioned in 1912 for Greenlawn Cemetery to commemorate Confederate prisoners of war who died while imprisoned at Camp Morton in Indianapolis.” The memorial was actually installed in 1909, but it was indeed erected to memorialize roughly 1616 Confederate prisoners of war who died in Indianapolis, as well as perhaps 20 sympathizers and at least one enslaved man identified only as “Little Toe” who was captured at Fort Donelson in February 1862 with most of these prisoners. Mayor Hogsett’s tweets indicated that “The grave monument was then relocated to Garfield Park in 1928 following efforts by public officials, active in the KKK, who sought to `make the monument more visible to the public.’” The Mayor concluded that “Whatever original purpose this grave marker might once have had, for far too long it has served as nothing more than a painful reminder of our state’s horrific embrace of the Ku Klux Klan a century ago.” Read the rest of this entry